A federal watchdog estimates that 41 percent of school districts need to update or replace heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems in at least half their schools, underscoring a significant infrastructure need for schools even as they prepare for the novel coronavirus when they reopen.

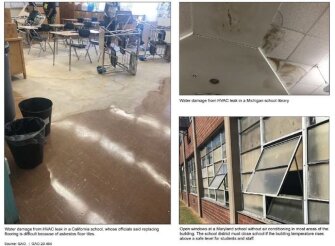

In a report published Thursday, the Government Accountability Office said that several schools it visited had HVAC systems that leaked and caused damage, and that if not addressed, “such problems can lead to indoor air quality problems” and even force schools to temporarily close while the issues are fixed. In all, the GAO estimated that 36,000 schools need HVAC updates.

The GAO report does not deal directly with the specific challenges posed by COVID-19; the report says that the “hazardous conditions” it refers to that can lead to school closures don’t include the virus.

However, while school infrastructure is regularly a focus of education legislation and lobbying on Capitol Hill, it could become more important during the pandemic. Last month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited guidance to help schools reopen, and among the recommendations is that schools should “ensure that ventilation systems operate properly” and should increase ventilation of outside air by opening windows and doors, unless it creates concerns for students with asthma.

The additional health measures schools are considering or might feel are necessary for the next school year, and how much they’ll cost, will be a major issue this summer as education officials prepare for the 2020-21 school year. It’s one reason why they say they need additional financial resources, even as state budgets take a hit due to the economic slowdown caused by the pandemic. The CDC guidance also touches on potentially difficult spots with respect to coronavirus-related safety protocols like water fountains.

“Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, outdated and hazardous school buildings were undermining the quality of public education and putting students and educators at risk,” said Rep. Bobby Scott, D-Va., the chairman of the House education committee, in a statement responding to the GAO report. “Now, the pandemic is exacerbating the consequences of our failure to make necessary investments in school infrastructure.”

It’s still unclear to what extent school-age children can and do transmit the coronavirus, although they have mostly escaped major health problems associated with COVID-19. However, older school staff and those with chronic health conditions, to say nothing of others they might come into contact with, are at higher risk of COVID complications.

In 2018, Sabrina Lee and Jake Varn wrote about school infrastructure for the Bipartisan Policy Center and stated that, “Importantly, low-income communities and communities of color have been, and continue to be, disproportionately affected by poor school conditions.” And black people in particular have been hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic, according to the CDC.

The GAO found that the share of schools estimated to need major HVAC help, compared to the share needing significant upgrades for roofing and structural integrity, was the largest. The report also estimated that 21 percent of districts need key updates or replacements for “indoor air quality monitoring” in at least half their schools.

‘Serious Consequences’

Remember that the CDC guidance we mentioned above recommends bringing in more outside air by opening windows and doors, in addition to ensuring that mechanical ventilation systems work well. Of course, in some schools, leaving windows and doors open for extended periods during the first few weeks of the school year could create an uncomfortably warm and humid environment for students, to say nothing of colder periods.

A recent article posted by the CDC about a coronavirus outbreak linked to a restaurant in China notes that “droplet transmission was prompted by air-conditioned ventilation.” The piece recommended increasing distance between tables as well as “improving ventilation.” The CDC guidance recommends spacing students’ desk farther apart than normal, although that presents new challenges around classroom and school space.

In the case of the restaurant in China, the problem was that the air-conditioning system functioned poorly and just moved the virus around the room, rather than properly diluting and moving the air out of the room, said Rick Hermans, who’s in charge of school issues on the COVID-19 task force at the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). Yet schools often put off maintenance of HVAC systems that would address such problems, he said.

“There’s always difficulty certainly in staffing the schools themselves with what we refer to as engineers, people who are responsible for operating the systems within the buildings,” said Hermans.

Here’s a portion of the GAO report that also highlights this issue:

“Officials in several school districts we visited said there are serious consequences to not maintaining or updating HVAC systems, including lost educational time due to school closings and the potential for mold and air quality issues ... For example, officials in a Michigan district said about 60 percent of their schools do not have air conditioning, and in 2019, some temporarily adjusted schedules due to extreme heat. Without air conditioning, schools relied on open windows and fans, which were not always effective at cooling buildings to safe temperatures for students and staff, according to district officials.”

ASHRAE said in April that, “In general, disabling of heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning systems is not a recommended measure to reduce the transmission of the virus.” And the group recently released a pandemic-focused guide for schools looking to reopen.

Among other things, that guide says to create a district-wide health and safety committee, and develop policies for staff and contractor use of personal protective equipment, often referred to as PPE; the CDC guidance for school reopening mentioned above says all school staff should wear face coverings.

Hermans said that one temporary solution for schools is to buy portable HEPA filters and put them in classrooms to clean the air. However, he said, those devices can be noisy and distracting for students. And since a lot of classrooms don’t have air conditioning, he noted, “In a lot of schools, the open window is the only cooling that classroom gets” and therefore can be helpful to a certain extent.

The GAO report said some schools prioritize safety infrastructure over other building systems. It highlighted one school in Florida that bought new security cameras, even as a faulty HVAC system required maintenance workers to go up to the roof every day to address it.

It’s far from a sure thing that a new federal coronavirus relief package will include help for these areas. In early 2019, congressional Democrats introduced the Rebuild American Schools Act that would provide $100 billion for school infrastructure needs, including $70 billion in direct federal spending. However, that bill was not included in the coronavirus aid bill passed by the House last month.

Images via Government Accountability Office, “School Districts Frequently Identified Multiple Building Systems Needing Updates or Replacement.”