The growing research base for character education programs shows benefits for students' social—and academic—skills.

It’s time for the morning meeting in Jessica Kimmel’s 5th grade class at Hyde Elementary School, and the children are wrestling with a problem. It seems that Kimmel has heard her students saying “shut up” to one another lately. Now, the class has to figure out how to stop before it becomes habit-forming.

“You can tell people, ‘You shouldn’t say that because it’s a bad word,’” offers one girl, Roslynn, from her corner by the bookcase. “It would be bad if you said that around little children on the playground, because they look up to you.”

Polly, the girl in the fuzzy pink sweater sitting on the floor next to Roslynn, suggests that friends can keep watch to prevent each other from saying the words.

“We could put sticky notes on our cubbies,” another student volunteer offers.

In an education world that is increasingly geared toward attaining high scores on standardized tests, all this talk about behavior and problem-solving might seem out of place. In some of the classrooms here at Hyde Elementary, however, it’s the way school is done.

Besides tackling their own behavior issues, these 5th graders begin the day by shaking hands and greeting their classmates. They pledge every morning to “play with everyone” and to “treat others the way I want to be treated.” And, when students finish sharing a bit of personal news in front of the class, they pause to announce, “I’m ready for questions and comments now.”

The focus on developing good character at the 172-student public school here in Washington comes from a Massachusetts-based program called The Responsive Classroom. Whether these lessons will one day help Polly, Roslynn, or the other children in this class become better students, more responsible citizens, or more caring adults is an open question.

Still, a growing number of studies are beginning to suggest that programs like this one just might help.

Once built on testimonials and program evaluations, the research base for character education programs—and other kinds of social learning efforts—is starting to mount.

“We’re seeing the beginning of some positive results,” says Roger P. Weissberg, a professor of psychology in education and the director of the Consortium on Social and Emotional Learning, a 9-year-old group based at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Experts such as Weissberg say the change is coming for two reasons. First, the U.S. Department of Education, spurred by rule changes in its character education program, broader changes in federal education law, and a new research-grant program, is pressing the field to produce more-rigorous studies—and helping to pay for a few of them.

The second reason is that the field itself is beginning to cast a wider net in its search for effective programs. What experts have found is that comprehensive, effective programs aimed at nurturing positive character traits and social skills in children often contain many of the same ingredients as comprehensive, effective programs designed to prevent violence, drug abuse, teenage pregnancy, and a host of other negative outcomes.

When experts expanded the research lens to include all of those kinds of programs, the pool of proven programs grew. What’s more, much of the newer research also suggests that some of the best programs can increase academic achievement in the bargain.

“Behaviors tend to cluster together, and kids who do one of these types of behaviors tend to do others,” says Brian R. Flay, a professor of public health and psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “People say you’ve got to have one type of program to reduce violence and another to reduce drug use. Well, we’re showing they’re wrong.”

Rude Awakening

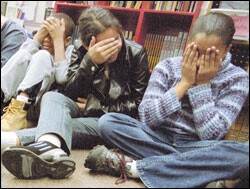

|

Students at Hyde Elementary School in Washington play a game during the morning meeting that starts each school day. The gatherings help address the 5th graders’ social development and teach them to get along with one another. |

The broad field that encompasses character education, prevention, and other kinds of social-learning programs got a rude awakening in the early 1990s, some scholars say. The wake-up call came from a study suggesting that Drug Abuse Resistance Education, despite being used in every state and in more than 80 percent of schools, was ineffective. The program, known as DARE, has since been revamped.

“Not only did it not work— it unquestionably didn’t work,” says Marvin W. Berkowitz, a professor of character education at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. “If you have a drug problem in your school and you use DARE to reduce it, it was like putting rubbing alcohol on your foot for a headache.”

Berkowitz is working with the Character Education Partnership, a Washington-based umbrella group, to put together a review of the research on a wide range of K-12 programs that include improving some aspect of children’s character as at least one goal. He said he was surprised to find studies for 300 such programs.

“The quality varies widely,” he notes. Nonetheless, he says, at least 15 programs—and possibly 20—have a research basis that he considers strong. They include the Child Development Project, a schoolwide program devised over two decades by researchers in Oakland, Calif.; Positive Action, a commercial model based in Twin Falls, Idaho, that focuses on promoting “prosocial” skills and healthy behaviors in children; Second Step, designed by the Seattle-based Committee for Children and originally marketed as a violence-prevention program; and The Responsive Classroom.

Developed in 1981 by the Northeast Foundation for Children, a nonprofit group based in Greenfield, Mass., The Responsive Classroom is used in about 20 states. It integrates social and academic learning and has as one of its hallmarks an extensive teacher-training program. It takes three years for teachers to become fully certified in the approach.

‘We think you have to care deeply about the whole child, especially the education of character and civic responsibility.’

“We think you have to care deeply about the whole child, especially the education of character and civic responsibility,” says Chip Wood, a former social worker, teacher, and principal who helped create the program. “That, in my view, is just as important as academics.”

Early on, Wood says, the small foundation saw the need to build a research base for its work. The group assembled an independent research-advisory panel and began looking for sponsors to underwrite studies. Since then, the group has racked up a handful of small-scale studies. The largest to date, which is underway, involves children in 12 Connecticut schools, half of which are using the program.

So far, the studies show that children in classrooms where teachers adhere to the approach score higher than children in nonprogram classrooms on scales designed to measure five attributes of character: cooperation, assertion, responsibility, empathy, and self-control. The findings also point to decreases in problem behavior in Responsive Classroom schools, to more teacher satisfaction, and to some increases in academic achievement.

“As you facilitate social development, you are concurrently, for many kids, advancing their academic function,” says Stephen N. Elliott, a professor of educational psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the associate director of its center for educational research. He did most of the studies on The Responsive Classroom, but he also points to a growing body of other research from both this country and abroad that suggests that social skills are “academic enablers.”

Most notable, he says, is an Italian study published three years ago in Psychological Science that tracked 294 children from 3rd grade to 8th grade. The most powerful predictor of academic achievement in 8th grade, the researchers in that study found, was the youngsters’ positive social skills five years earlier.

“This is big stuff,” Elliott says.

Free to Teach

Addressing children’s character development was not rocket science, though, to Anne Jenkins, Hyde Elementary School’s principal.

“It’s how you do that social piece that frees you up to teach,” observes Jenkins, who has been a trainer for The Responsive Classroom for more than eight years. “That’s when wonderful things start to happen in the classroom.”

When children don’t have those skills, she explains, teachers spend too much time negotiating, keeping order, and directing activities.

Jenkins learned about The Responsive Classroom through a summer course. With or without the research to back it up, she says, the approach made intuitive sense to her. Now, she’s hoping to infuse the model into every classroom at Hyde, an economically diverse school tucked in a busy Georgetown neighborhood in the nation’s capital.

|

Carol G. Allred, the developer of the Positive Action model, says most educators are more impressed with word-of-mouth endorsements from other educators than they are in the research attesting to programs’ efficacy. Although she began putting together studies on her program in the late 1970s, she found schools weren’t always interested in those results.

“They all give it some kind of lip service, but from a marketing point of view, it just wasn’t worth the effort,” Allred says.

Likewise, up until last year, the total of $54 million in grants that the federal Education Department had distributed to states through its 8-year-old Character Education Partnership program put no special emphasis on research. Beginning last fall, though, states and districts that qualified for the grants were required to adhere to tougher evaluation guidelines and to use the money only for “scientifically based” programs.

The changes came on the heels of similar efforts to transform the violence- and drug-prevention programs financed through the federal Safe and Drug-Free Schools and Communities Program.

Still, if the gold standard for research on effective interventions is randomized experimental trials, the field still has far to go, experts say. Such experiments, which involve randomly assigning schools or classrooms to experimental or comparison groups, are rare among the studies piling up in the field so far.

One roadblock for program developers has been cost. Experimental studies are expensive, and many of the programs are home-grown efforts. Without backing from a foundation or a corporation, some may wither away amid the new press for more scientific research.

To prime the pump, the Education Department’s research arm, the Institute of Education Sciences, earlier this year announced plans to give up to eight four-year grants to researchers interested in taking programs that stress the development of children’s social skills and character with some “soft” studies behind them and testing them out more rigorously in randomized experiments. The first round of those grants is due to be announced later this year.

Another gap in the research, observers say, is the lack of any studies gauging the extent to which schools across the nation are using any kind of character education programs. Even though the Character Education Partnership has awarded grants to some 45 states, no one knows how widely the programs have penetrated classrooms.

Elements of Success

|

Teacher Jessica Kimmell leads her 5th grade class at Hyde Elementary in the meeting that is part of the Responsive Classroom character education program. |

From the studies conducted across all these related fields so far, however, Berkowitz says he has identified—at least preliminarily—some elements that seem to be common to successful character education.

He found, for example, that effective character education programs are usually part of a more comprehensive model for school improvement.

Moreover, he says, the programs work best when students see their schools as caring communities and bond with them.

He also says that principals need to take an active role in those efforts, and that all adults should become exemplars of the character traits they are trying to instill in children.

“If adults don’t walk the walk, it doesn’t work,” says Berkowitz, who hopes to complete his three-year-long study this summer. In the meantime, the Coalition for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, known as CASEL, recently published the results of a similar review. In that report, titled “Safe and Sound,” the group cites 22 programs that it considers to have a solid research base, good staff development, and sound curriculum design.

Proponents of such programs are hoping that the good news dribbling in from the research front will help to counter what they see as their continuing marginalization in schools. With the growing emphasis on academic standards and raising test scores in core subjects, too many educators and policymakers regard these more socially oriented programs as “touchy feely” and time- consuming, according to Berkowitz.

Even Jessica Kimmel, the 5th grade teacher at Hyde Elementary School, found herself bowing to that kind of pressure at the beginning of the last school year. With the prospect of standardized tests breathing down her neck, Kimmel, who is in her fourth year of teaching, decided to forgo some of the upfront lessons that go into The Responsive Classroom approach.

Instead, she launched right into the academic program. Students were disruptive all year, and the pace of learning suffered.

“I paid the price dearly,” recalls Kimmel, as she surveys her 5th graders working quietly and industriously at their tables. “I’ll never do that again.”

The Research section is underwritten by a grant from the Spencer Foundation.