Fifteen years ago, the school system in this small city across the Mystic River from Boston was a case study in failure. Test scores languished, school buildings were a century old, and middle-class families had long since made an exodus to the suburbs.

“We were the laughingstock of the state,” recalled Morrie Seigal, who has been on the school committee here since 1975.

Desperate for change, Mr. Seigal and his colleagues voted in 1989 to hand the management of Chelsea’s schools over to Boston University. The unprecedented offer made the university the nation’s first—and only—to run an entire public school district. The partnership has far outlasted the initial 10-year contract. In fact, the Chelsea school committee last year renewed the agreement with the private university until 2008.

Today, the 5,600-student district, which serves mainly low-income Latino students, is one of only three urban districts in Massachusetts that met goals for adequate yearly academic progress under the federal No Child Left Behind Act.

Chelsea boasts an early-childhood-learning center that is the envy of wealthier towns, and a major construction project in 1997 helped erect new schools to replace buildings that had been crumbling for years.

Boston University has provided professional development and scholarships for Chelsea’s teachers, started a private foundationthat has raised almost $12 million for the schools since 1991, developed a family-literacy program, and set up a school-based dental clinic that provides free checkups for students.

Along the way, the partnership has survived lawsuits from the state teachers’ union and from a coalition of community groups, as well as a financial crisis that left the city in state receivership for three years.

The ties to the university are deep enough that the school committee halted a national search to replace former Superintendent Irene Cornish this past summer. Overwhelming public support for Thomas S. Kingston, a Boston University humanities professor who had served as the assistant superintendent for 10 years, won him the top job, despite the fact that he had never declared himself a candidate for the superintendency and had planned to return to his post at the university.

Mr. Kingston describes progress here as more steady than dramatic. Until 1997, he said, Chelsea continued to have some of the lowest test scores in the state. And still today, the district struggles to match improvements in the early grades with gains at the middle and high school levels.

“The university thought reform would be easier than it was,” Mr. Kingston said during an interview this month in his office at Chelsea City Hall. “But people were not aware of how deep the constraints were, how low the expectations were, and how frustrated and demoralized teachers were.”

The first few years of the partnership were tumultuous, he acknowledged. “If someone comes in on a white horse to save you, and you don’t really know that you are drowning, you’re going to resent it,” he said. “There was a lot of resentment. We sort of came in like gangbusters, and with some insensitivity.”

Gradual Acceptance

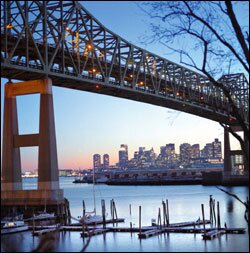

Chelsea has the scrappy attitude of a gateway city for immigrants. Less than two square miles, tucked into a sliver of space not far from Boston’s airport and downtown, the city has for the past century attracted newcomers. Immigrants from Latin America, particularly Honduras and El Salvador, have replaced workers of Irish and Polish origin. More recently, refugees fleeing such trouble spots as Sudan and Afghanistan have arrived in growing numbers—alongside young Boston families bringing gentrification and rising housing prices to this city of 35,000 residents.

When the Tobin Bridge was built in 1950, splitting Chelsea in half and leveling homes in its wake, middle-class families began leaving for greener pastures. The “Iron Monster” became a symbol of the city’s decline. By the 1980s, Chelsea was grappling with a familiar litany of urban ills. Only half its students were graduating from high school, and the city’s average income was 44 percent lower than the state average.

By 1988, the late Andrew Quigley, the owner of the Chelsea Record newspaper and a school committee member, thought swift action was needed. He and then- Mayor John Brennan asked John R. Silber, who was then the president of Boston University, to step in and help. A longtime advocate for higher standards in public education, Mr. Silber once had urged the Boston school committee to let the university run its city’s schools, but was rebuffed.

A year later, a divided Chelsea school committee voted to approve turning over district operations to a university management team, and the Massachusetts legislature approved the deal. The decision to bring in Mr. Silber, a nationally recognized but polarizing leader known for his acerbic style and fierce opposition to bilingual education, set off an explosive response.

The late Albert Shanker, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, denounced the move, the local affiliate union filed a lawsuit, and a closely watched story of turf battles, gradual acceptance, steady improvement, and still-lingering tension began.

Ed Marakovitz, the director of the Human Services Collaborative, a social-service provider in Chelsea, believes the university deserves credit for raising expectations and modernizing school facilities, but has fallen short in other areas.

“The biggest failure has been their relationship with the community,” he said. But after years of animosity, Mr. Marakovitz sees things improving. Two Latina community activists were elected to the nine-member school committee, as Massachusetts school boards are known, on Nov. 2.

“There was a time when I felt there could be nothing but confrontation,” Mr. Marakovitz said. “I don’t feel that way anymore.”

The school committee still meets, but acts as an advisory panel to the university’s management team. While the panel can veto a university decision with a majority vote, it has done so only once in the last 15 years. In the early years of the partnership, the management team decided not to provide condoms to students at Chelsea High, but the committee overruled that decision.

Some critics say that the record proves that the school committee has been reduced to a rubber stamp. Gladys Vega, a parent and community activist, said Boston University has showed little concern for the community from the beginning.

“We have been guinea-pigged,” Ms. Vega said. “They have very limited respect for parents. If you question them, you are a troublemaker.”

Ferna O’Connor, the president of the Chelsea Teachers Union and a Chelsea native, thinks Boston University gets too much credit for what she sees as a mediocre job.

“You have this worldwide university, and Chelsea is a tiny little city. If BU, with all of their success and money and authority, couldn’t do a better job of keeping the kids above water, I don’t call that a success,” she said.

Ms. O’Connor has little doubt about what will happen after the university’s departure in 2008, as requirements for making academic progress continue to intensify.

“I think we are going to fall flat on our face,” she said. “It’s like having your mother take care of you until you are 50, and then she dies and leaves you alone.”

‘Long Way to Go’

Educators in Chelsea clearly have their work cut out for them. A high student-mobility rate, which hovers at about 35 percent, means teachers in Chelsea often lose pupils in the middle of the year. Many new immigrants struggle with cultural adjustments. Three-quarters of the students live in homes where English is not the first language. Adding to those challenges, a controversial state ballot initiative that passed two years ago ended bilingual education, requiring English-immersion classes for students learning the language.

“They still have a long way to go,” said Robert D. Gaudet, a senior research analyst at the Donahue Institute at the University of Massachusetts, a statewide research organization. But he said Chelsea’s state test scores have since 1998 consistently exceeded scores predicted by the district’s demographics.

“It’s a school system that does better than you would expect,” he said. “What you see in Chelsea is a structure that is in place, and BU has to be credited with that.”

The heavily immigrant population is one of the reasons Chelsea’s schools began teaching the Core Knowledge curriculum last year. The program—founded by E.D. Hirsch Jr., the University of Virginia professor who popularized the importance of “cultural literacy”—stresses the understanding of a common body of facts across a range of subjects in grades K-8.

Edgar Hooks Elementary School here showed enough improvement on state assessments in English and mathematics to be one of five elementary schools to win a state award recognizing its progress last year.

One recent weekday morning, about 20 4th graders were spread out on a rug at the school as their teacher read a Judy Blume book about sibling rivalry. In this “writers’ workshop,” students have been working on how writers create mood, settings, and narration in their stories.

“When I can read something and I can hear you in my head, that’s voice,” the teacher explained. After discussing the story, the students moved to their desks and began writing their own paragraphs.

The school’s intense focus on literacy and writing instruction, said Principal Coralie Kelly, has been especially helpful, because most of her students speak Spanish with their families and have very few books at home.

For Ms. Kelly, who began her career as a teacher here more than 30 years ago, the improvement her school and district have made would be hard to imagine without the support of Boston University.

She proudly shows off the school library that is stocked with 60,000 titles, and she credits the consistent leadership of the university with enabling schools to have these kinds of resources. Boston University has also provided ongoing professional development for its teachers. Things were different when she was teaching 6th grade back in 1970, Ms. Kelly said.

“I had no wall maps, and the books were outdated,” she recalled. “I remember opening my desk and there wasn’t even a paper clip. The difference now is teachers have everything to do their job.”

Ms. Kelly admits that when the university assumed management here, she was far from a true believer.

“In the beginning, people didn’t like the idea of a takeover,” she said. “I wasn’t the most welcoming person. But the benefits are undeniable.”

Coverage of leadership is supported in part by a grant from The Wallace Foundation.