The 2006 Child Well-Being Index, released in March by the Foundation for Child Development in cooperation with Duke University and the Brookings Institution, suggests a general lack of progress for K-12 students, evidenced by flat scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, persistent achievement gaps, and falling high school graduation rates. In our view, this lack of progress does not stem from a lack of resources going into education. These have grown steadily.

—Lucinda Levine

A more likely culprit is an outmoded district system of school governance that lacks genuine results-based accountability. Chartering seeks to remove what the policy analyst Ted Kolderie calls school districts’ “exclusive franchise” to create and run public schools, and to inject into the system accountability for results.

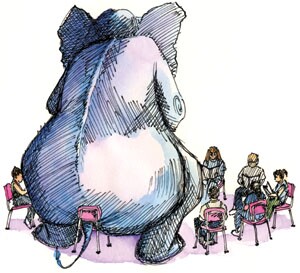

Fifteen years after the first charter school opened its doors, the full extent of chartering’s potential as a school and district improvement strategy remains unknown. Will the federal No Child Left Behind Act, the elephant in the school reform room, give chartering a lift or trample it entirely? And could chartering help achieve the law’s lofty goals for raising student achievement and closing achievement gaps?

These abstract questions are given substance by the law’s provisions permitting that schools failing to make “adequate yearly progress” for five consecutive years be converted into charter schools. Should states encourage or even force districts to pursue this remedy? If so, what is necessary for it to be effective?

The heart of chartering is the voluntary creation of public schools of choice that are accountable for results through a performance agreement—or charter—with a public entity, while being exempt from many regulations placed on traditional public schools. This approach was intended to provide new accountability mechanisms through both a social market and a contract with a government agency. It was also hoped that charters would provide a source of innovation and of direct competition that would help all public schools improve.

There are now over 3,600 charter schools, enrolling more than 1 million students, scattered across 40 states and the District of Columbia. While charter schools enroll less than 2 percent of public school students nationwide, these schools are a significant market presence in some urban districts. Dayton, Ohio, for example, boasts over one-third of public school students enrolled in charters, and charter enrollment in the District of Columbia is approaching 30 percent. Nationwide, a third of charter schools are located in large urban districts, as compared with 10 percent of traditional public schools.

There is little good evidence yet on charter schools’ effectiveness in raising student achievement. But there are clear signs of potential. The one study to use randomization to examine the impact of attending a charter school, conducted by the economists Caroline Hoxby and Jonah Rockoff, found that students chosen by lottery to attend charters managed by the Chicago Charter School Foundation outperformed students on the schools’ waiting list who remained in traditional public schools. In separate surveys of the research literature conducted in 2005, Bryan Hassel of Public Impact and Paul Hill of the University of Washington concluded that, while the quality of available research was poor, studies using more-reliable methods tend to show achievement in charter schools improving more rapidly than in traditional public schools.

Forced school conversions seem to strike at the heart of chartering, with its emphasis on voluntarism and choice.

Although much more evidence is needed before we reach strong conclusions about the overall effectiveness of charter schools, it is already clear that some of the most impressive and innovative new models for urban education have emerged within the charter sector, that charters have brought new blood into the teaching profession, and that demand for seats in charter schools remains high. There is also evidence that competition from charters has spurred traditional public schools in some areas to improve their performance—and no evidence that the presence of charters has had an adverse impact.

But there are also hints of problems that, if unchecked, could limit chartering’s success. While charter schools have maintained bipartisan support in Washington, entrenched local opposition often limits the funding they receive, preventing them from gaining access to facilities on equal terms with other public schools. A 2005 Fordham Foundation study of 16 states and the District of Columbia showed that charter schools receive about 22 percent ($1,800) less in per-pupil public funding than district schools surrounding them. Moreover, state caps on the number of charter schools, or on charter school enrollment, are already binding in at least 10 states. Finally, some charter authorizers are ill-equipped to provide schools with sufficient support, and few authorizers seem willing to shutter bad schools. A lax approach to charter granting and renewal threatens to allow bad apples in the charter crop to spoil the rest.

The No Child Left Behind law requires charter schools to demonstrate adequate yearly progress toward full proficiency in mathematics and reading, or face sanctions as other public schools do. Some charter advocates complain that this provision stifles innovation, but accountability for educating students to basic proficiency in core academic subjects is a reasonable requirement—provided it is administered in a sensible way. Many charter authorizers have wisely incorporated the federal law’s targets for student achievement into their performance agreements with schools, not as a substitute for more-complex accountability metrics, but as a complement to them. The end result may be the best of both worlds: Oversight from charter authorizers can complement the federal law by providing a richer model of accountability that will keep schools from excessively narrowing curricula. And state accountability systems can force authorizers to get tough and provide them with leverage to close ineffective schools.

Indeed, rather than stifling chartering, the No Child Left Behind law may well aid in its expansion. With more low-performing schools moving toward the year-five restructuring deadline, districts could exploit the law’s provision permitting these schools to be converted into charters. Or, perhaps more likely, states could encourage districts to do so.

But forced school conversions seem to strike at the heart of chartering, with its emphasis on voluntarism and choice. And pitfalls are associated with the strategy: Unenthusiastic districts may “charter lite,” not giving schools necessary autonomy or resources. As Greg Richmond, the former head of the Chicago district’s charter school office, has said, “The temptation will be to just change the sign over the door and call the school a charter school.” Given the lack of a uniform charter school model, creating a new charter could be the weakest restructuring option available under the No Child Left Behind law, enabling districts to reset a school’s restructuring clock without ensuring authentic change. Nor do districts necessarily know how to develop and support a performance-contracting approach. They have little or no experience in creating or authorizing new schools of choice, monitoring schools against performance benchmarks with a view to results-based accountability, or encouraging genuine family involvement in the school planning or selection process.

Rather than stifling chartering, the No Child Left Behind law may well aid in its expansion.

For chartering under the No Child Left Behind law to proceed with some modicum of success, at least three necessary—though perhaps not sufficient—conditions must be met. First, state and federal laws must be in place to support the creation of genuine charters in sufficient numbers to serve many students. For example, state caps on the number of charter schools and on charter enrollment should be eliminated, at least for schools restructured under the No Child Left Behind law. States should also ensure that charters receive access to state and local program and capital funding on equal terms with traditional public schools, and have sufficient autonomy to pursue their distinctive missions. To encourage reluctant states to take these steps, the federal government should consider allocating aid for restructuring schools under Title I only to states that allow for the creation of charter schools and treat them equitably.

Second, a strong authorizing and monitoring process, embedded in a genuine performance contract, must exist, with alternative authorizers like state universities, specially created chartering agencies, or elected officials empowered to create new schools. The National Association of Charter School Authorizers, leading the way among organizations defining best practices in this rapidly evolving field, emphasizes the importance of clarity, consistency, and transparency in developing and implementing authorizing policies. Allowing nondistrict entities to grant charters, as some states now do, has encouraged the adoption of such practices and should be imitated widely.

Third, there needs to be a well-defined community- and civic- engagement process for creating new charter schools. This process should include ample support for providing families with good information on schools; procedures for matching students with these schools; and ways of providing the supports and services families and children need to succeed in these schools.

Given the potential pitfalls associated with converting persistently low-performing schools into charters, states and school districts may well pursue less-aggressive restructuring options. This would be unfortunate, as there is scant evidence that other interventions have worked to turn around failing schools. Achieving the No Child Left Behind Act’s goal of educating all students to proficiency will require a dramatic expansion in the supply of high-quality public schools in traditionally underserved communities. Granting charters to proven providers, selected by the local community and supported and held accountable by capable authorizers, offers a promising strategy for accomplishing this essential task.