—Bob Dahm

It’s been 23 years between President Reagan’s warning of “a nation at risk” by a “rising tide of mediocrity” and President Bush’s advocacy of “no child left behind” by the “soft bigotry of low expectations.” Over the years, a lot has changed in the worlds of media, marketing, and public relations—and without changes of corresponding sophistication or significance in education communications. More “woefully inadequate” than the performance of U.S. schools and students is the degree to which communications in the education marketplace advance meaningful changes that yield better teaching and learning.

Even corporations dominating other fields find that they can’t use standard tricks of the trade to command consumer opinion or market share in education. Those who do well in the education market focus on essential aspects of public engagement. We’ve learned the hard way that traditional marketing and PR tactics predicated on the quick sale of ideas proffer perilously weak support—insufficient to sustain commitment or muster the political will to affect policy and practice in education.

Here are a dozen lessons learned during decades of reform:

• Publicity and promotions are not enough to make a real difference or a lot of money in education. Once upon a time, it was sufficient to raise awareness, create a sense of urgency, and issue a call to action. Today, people and organizations advancing products, services, or ideas in education face intense public scrutiny and heightened demands for accountability. “Getting to yes” means helping citizens and elected officials in their search for answers to complex school and community problems, as they weigh the pros and cons of any given course of action, and before they settle on an informed judgment that sustains commitment to a public or public-sector product, service, or initiative—and inspires action over the long haul.

• Invest time and talent to create informed education consumers, melding community relations, public affairs, marketing, and media savvy so that people are equipped with sufficient knowledge, obvious incentives, and ample opportunities to make sound judgments about education products and services that affect their futures. People want to participate in education decisions. Make it easy. Create two-way channels of communication that allow for give and take, for ideas to mature.

• Be patient—and prepare for fallout from the unintended consequences of policies created, ironically, to meet the public’s demand for better schools that serve all students with greater accountability. Sure, parents and policymakers cry out for information. But too few use the available data. Taxpayers want measurable results, but cringe at the cost of investments in assessment or research on teaching and learning.

• Listen carefully to what the public is saying—and use polling data wisely. Education has discovered publicity polling, along with the value of hard data. The pressure to document results has increased appetites for opinion data that highlight changes in attitudes toward education. Like their counterparts in the corporate arena, education leaders who want to get their issues in the news have come to understand the value of quantifying information to satisfy media and public demand for hard numbers.

But snapshot surveys tell only part of the picture, from one moment in time, and as such, may not merit or portend changes in policy or practice. Words in opinion polls mean many different things. Consider the danger of “stop thought” words, loaded with connotations that thwart discussion and make many polling questions trivial. And remember, attitudes toward education are influenced by the larger fabric of public opinion, just as schools reflect the larger conditions in society.

• Beware the perils of pandering to public opinion. Education and democracy are inextricably linked. As public institutions, schools require the “consent of the governed.” They must operate “in the sunshine” and are not effective without public support. But public opinion is often ill-informed, morally wrong, frivolous, illegal, or beyond capacity. People often have little understanding of real options to which informed leaders have already gravitated—and most of us have little time to consider matters fully. (The average consumer spends more time comparing electronics equipment than examining the options available in the public schools.) Frankly, one of the most significant problems is that the education establishment reacts to what it perceives public opinion to be, rather than asserting leadership.

• Gain support by behaving like experts, leading the public to new conclusions about public education. By taking the long view, the education establishment can make a good case for why nothing but a public system can respond to the challenges we face as a nation. Simply aligning resources and responses to public concerns is too little, too late. Leaders have to project how the public education system is integral and indispensable to America, and lay out a course of action to meet these challenges. Medicine doesn’t respond to fears about disease by empathizing with the public. It makes announcements about new solutions, new research—reinforcing the perception that the medical establishment is leading the way, even if cures are a long way down the road. Education could learn from this approach.

• Help people ask good questions. It’s not enough to make people aware, to provide accurate information, or to disseminate or debate research—especially if questions are misguided. Purge jargon and open up conversations with the public—defining terms as you go, reaching consensus on the course of action. Consider, for example, parents at a back-to-school night who pepper a teacher with questions about whether she is teaching “whole language” or “phonics.” The teacher may have a hard time explaining that both are possible and part of her approach, and that either-or distinctions are moot in this case.

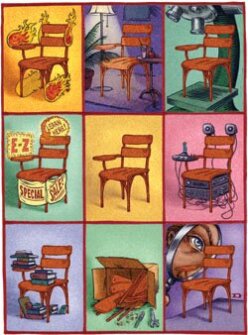

• Paint a variety of pictures of “success” with significant, compelling evidence beyond the limitations of test scores. Show how education products or initiatives aren’t “like your father’s Oldsmobile.” One parent told me of a museum docent’s comment as she escorted students on a field trip: “Which school do these students come from? They are so respectful, so well-behaved.” These are some of the nontraditional results to showcase that mean a lot to people and interest media.

• Take time to educate the education reporters. Coverage of education has increased, and so has the number of education reporters. However, the “education beat” remains one of the less prestigious in most media outlets. And many reporters and editors have little to no historical perspective or firsthand knowledge about the developments in education outside their communities that so profoundly affect the present.

• Keep corporate leaders at the table. Engaged private-sector leadership is an invaluable asset in education improvement. Business leaders have moved beyond the adopt-a-school mentality to focus on bottom-line results that affect their ability to hire and retain employees and serve customers. How novel it seemed, decades ago, to have Owen B. Butler, the chairman of Procter & Gamble Co., testify before Congress with teachers’ union leaders Mary Hatwood Futrell and Albert Shanker, demanding adequate funds for Head Start. How common it has become for business leaders to provide impetus for school change, investing appreciable corporate and personal resources.

• Be willing to consider real structural changes to accommodate the breadth of community involvement in decisions about teaching and learning. Seek “outsider” input in areas that used to be the sole province of the schools: designing new assessments, approving new graduation requirements, setting standards, providing advice on new construction, and hiring key staff members.

• Make communications an engine of the learning enterprise, not a caboose in the drive for educational change. Most administrators and teachers have little or no communications training. (Unfortunately, schools of education don’t provide a lot of coursework in public relations.) School PR officers are often reacting to decisions from the top—spinning out stories, Web sites, and events without benefit of strategic communications thinking, investment, or counsel, and without support from expertly qualified peers or mentors who have experience in changing what people know and do in the education enterprise.

Smart organizations and leaders in education know it is not enough to influence public opinion. Long ago, they stopped “painting lipstick on the pigs” of public policy to engender “buy in” or to “sell” ideas. Purveyors of products, services, and initiatives succeed in the public business of teaching and learning when they artfully blend inspiration and knowledge with time, talent, and resources to change how people act.

Generations of students have passed through schoolhouse doors in the years Americans have been wringing their hands about the quality of education and wrestling with innovations designed to revamp a centuries-old model of teaching and learning. A sane person might be daunted. But it took over 200 years for public education to evolve into the system we know now, with all its problems and potential. Why on earth do we think we can bring about fundamental changes in attitude or mobilize consumer demand in a month’s time, a year, or even in a child’s lifetime—especially if we continue to communicate as if it’s business as usual?