It’s a new day, of sorts, for the nation’s largest union.

Democratic majorities in Congress should give the National Education Association friendlier treatment in Washington than it’s received during most of the past six years. And in statehouses across the land, two-thirds of the gubernatorial hopefuls the 3.2 million-member teachers’ union supported in November have taken office.

Backing up the electoral clout are sheer numbers. The union expects this to be the third year of significant membership growth—about 40,000 new members came aboard during the 2005-06 school year, according to Executive Director John I. Wilson.

Union officials point to an organizational overhaul begun in late 2004 as one big reason for the ballot-box and membership-sign-up successes. What’s more, they say, the second phase of the makeover, just completed, will beef up the union’s ability to speak authoritatively on questions of education policy and practice.

Yet how much the National Education Association can make all that pay off remains a guess, given escalating pressures from friends and foes alike and the changing education landscape. Both the NEA and its smaller peer, the American Federation of Teachers, face a new and less doctrinaire group of critics, some drawn from Democratic Party ranks. Those critics and many of the civil rights groups that have been traditional allies of the unions are impatient with the pace of student progress among the nation’s poor and non-English-speaking students.

At the same time, federal budget deficits and an increased productivity mind-set among lawmakers are ruling out big-spending solutions. So, sometimes, instead of seeing lots more money for schools, the unions are getting closer scrutiny of contracts that appear to give teachers more generous deals than those offered to private-sector workers.

External pressures to step up school improvement aren’t the whole story, though. The NEA’s history since the early 1980s suggests that it has fumbled the reins of reform against a variety of political and economic backdrops. The AFT fared at least marginally better under the legendary Albert Shanker, who died in 1997.

Now, both unions are being tested most visibly by the federal No Child Left Behind Act, the nation’s main vehicle for school improvement, which is up for reauthorization this year. Both have called for substantial changes in the law’s provisions. Whether the unions will be able to shape that or other parts of the national agenda for school improvement hinges not just on their political muscle. As a new Congress and new state leaders set to work, the unions must bring credibility to their efforts as self-described proponents of public education.

This is the first of two articles looking at how the NEA and, next week, the AFT are stacking up as reform leaders.

Naysayer Image

The movement to put high-quality education at the center of the NEA’s concerns may have reached its peak in the late 1990s, with then-President Bob Chase’s “new unionism.”

Launched with a 1997 speech by Mr. Chase at the National Press Club in Washington, the undertaking largely followed a blueprint from the Kamber Group, a Washington public relations firm that had examined the union’s external communications and issued a report to NEA leaders that year. The report suggested that Mr. Chase admit publicly to some bad teachers in the ranks and take a couple of actions in support of education quality that would help the union shake its obstructionist image.

MEMBERSHIP: 3.2 million teachers, aides, other school workers, higher education faculty, students in colleges of education, and retired educators

STATE AFFILIATES: 50

LOCAL AFFILIATES: about 14,000 in all 50 states

EMPLOYEES: about 600

ANNUAL BUDGET 2006-07: $307 million

PRESIDENT: Reg Weaver

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: John I. Wilson

“NEA has been perceived as unwilling to acknowledge certain problems in education, costing the organization some credibility as a legitimate voice for reform,” the report said. There was also an impression, according to the study, that the NEA would pass up legitimate solutions because they might “inconvenience members.”

Some observers saw the new direction as an affirmation of the NEA’s traditional self-definition as a professional association rather than a union. As such, any stance by teachers would be for the greater good of the profession, the schools, and the students they serve.

The Kamber Group pointed out the immense public relations benefits of that image and urged the union to position itself as the No. 1 champion of public education.

Few observers of the union question Mr. Chase’s genuine interest in elevating the teaching profession to help schools improve. And the two-term NEA leader did bring about some changes in direction. He waged a successful campaign to allow teachers to evaluate their peers for example.

NCLB Strategy

In the end, though, his stance was not able to win the NEA any significant role in shaping the No Child Left Behind law after Republicans won the White House in 2000 and controlled Congress for all but a two-year period till this month. The AFT, which had championed standards and talked tougher about teacher shortcomings, fared better: It at least got the ear of the Democratic leaders who supported the bill.

If that wasn’t bad enough for the larger union, in the years since, the NEA has seemed to publicly obsess over the law, which was passed with big, bipartisan majorities and was signed by President Bush in January 2002.

Approved July 2006

First, NEA leaders said they’d help affiliates minimize harm from the law in their states. Then, in 2003, President Reg Weaver announced from the dais of the annual convention that the union would challenge the measure in court. “Any pretense of support has been swept away,” declared the union’s longtime legal counsel, Robert H. Chanin.

The suit, which charged that the law imposed illegal “unfunded mandates,” was later dismissed by a U.S. District Court and is currently on appeal.

The NEA was never able to find a state that would join its legal action. Connecticut, however, later brought a parallel lawsuit, and that led to another blow—this one indicative of tension over the law between the NEA and many minority groups. The groups see the measure’s focus on ending achievement gaps as a boon. Reportedly refusing to be swayed by the union, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, long an ally, filed a brief in opposition to the Connecticut suit.

The NEA responded by bumping up the priority of relations with minority groups, and trumpeting its own commitment to closing achievement gaps. But the tension is unlikely to evaporate, in part because the members of the union teach mostly in relatively untroubled schools.

Read the accompanying story,

“A lot of the time, in suburbs and small cities, you can pretend everything is great,” said Nancy Flanagan, an award-winning teacher and a member of the Michigan Education Association who is now studying for a doctorate in education. “The AFT is in big, tough cities,” she said, where the problems can’t be so easily ignored.

The union’s leaders are thus under pressure to fight the No Child Left Behind law. On the other hand, they lose if in the process they damage traditional alliances or their ability to do business on Capitol Hill, where little sentiment exists for throwing the law out or significantly weakening its accountability provisions.

Barbara Kerr, the president of the NEA’s largest state affiliate, the California Teachers Association, faults the national union for not coming down harder, earlier on the law. But she says that misstep has now been righted with a plan for its revision that was passed at the union’s last Representative Assembly.

“The most important thing to the membership at this point that the NEA has improved on is NCLB,” Ms. Kerr said. “That’s the biggie.”

To craft the plan, the national union rounded up affiliate leaders, among others, to shape what it calls a “positive” agenda. Last fall, it even disassociated itself from an Internet petition drive led by NCLB super-critic Susan Ohanian that has drawn thousands of teacher signatures. Nonetheless, the blueprint backs off from little the union has said before. It would allow states to cut down on annual tests and would require the federal government to foot the bill for any NCLB-mandated change, for instance.

“They don’t know where they are going,” scoffed one Washington policy insider, referring to the NEA. “Their sole purpose seems to be to fight NCLB.”

Like many people interviewed for this story, he did not want to be named for fear of harming his relationships with people in the NEA, with its $307 million budget and some 14,000 local affiliates.

Policy Push

The NEA’s top management recognizes that generating serious public discussion about teaching and learning has not been the union’s strength. So after now-Deputy Director John C. Stocks, who had been brought in from the Wisconsin affiliate in 2003, overhauled the NEA’s political and recruitment operations, his boss went to work on policy.

JULY 2, 2006: Reg Weaver is on the road about 265 days a year, trying to spread his message. The president welcomes delegates to the Representative Assembly at the Orange County Convention Center in Orlando, Fla.

—File photo courtesy of Rick Runion/NEA

JUNE 29, 2006: While in Orlando, he takes time out to don a Dr. Suess hat and read Green Eggs and Ham to elementary school children at the convention center.

—File photo courtesy of NEA

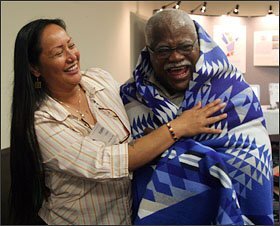

JUNE 20, 2006: Edith Leoso, the historic-preservation officer of the Bad River Native American Tribe in Odanah, Wis., presents Mr. Weaver with a blanket. He gave the keynote address at a tourism conference attended by representatives from many Wisconsin tribes.

—File photo courtesy of Paul M. Walsh/NEA

“NEA does [lobbying] and politics well,” observed Executive Director Wilson in the fall. “Now, we have to make sure the NEA does content well, too.”

Mr. Wilson’s solution was to create the Center for Great Public Schools, bringing together seven departments that he plans to oversee himself for a year. The work of the center will range from how the federal government’s “in need of improvement” label for schools affects minority communities to defining what successful schools need from policymakers.

“It will allow NEA to be more proactive … as opposed to just criticizing,” said Joel Packer, the union’s chief lobbyist on the NCLB law who now also heads one of those departments, which includes student-achievement and school improvement concerns.

With a closer-knit organization and a deeper policy operation thanks to the overhaul, Mr. Wilson envisions that the power of the state affiliates, often the most influential groups in state capitals, will translate into NEA clout. The parent organization has awarded grants to 10 affiliates—Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania—to help them win policies and funding for closing achievement gaps.

“We’re building a critical mass within the states,” said Mr. Wilson. “We think it’s important to moving a federal agenda.”

‘Role Clarification’

While John Wilson is often quietly circulating at NEA events, the union’s highest elected leader, President Reg Weaver, typically sweeps in bringing a boatload of bonhomie. Grinning, hugging, even kissing the occasional female hand, he is unmistakable, with or without the hand-carved cane he sometimes requires.

“He really connects with teachers,” gushed Denise Cardinal, who worked in the NEA’s communications office before becoming a spokeswoman for the Minnesota office of America Votes, an advocacy group.

Indeed, Mr. Weaver is known more for rallying the troops and pressing the cause of poor and minority students than for his interest in policy or research.

Both Mr. Weaver and Mr. Wilson, who was hired under Bob Chase, concede that they haven’t always clicked. “Having changed [presidents], you have got to work very hard on role clarification,” Mr. Wilson said of the transition after Mr. Weaver’s election in 2002. “We spent a lot of time doing that early on.”

More than his recent predecessors, the current NEA president prefers to control communication with the public. Reporters are welcome to call him, for instance, but calls to others in the organization must go through the public relations office.

Mr. Weaver says such care is deliberate. He’s proud of the work he’s done around “messaging.”

“I looked at people who didn’t like us, and I saw what brought them success,” the leader recounted in a recent interview. “They had a message, they were staying on message, and we didn’t have one.”

It took months of discussion, focus groups, and polling, but eventually the union arrived at a slogan that helps conflate the interests of the union and students. “Great public schools are a basic right for every child” is now emblazoned on union publications. “Basic right” is a nod to minority groups, many grounded in struggles for civil rights. “Every child” echoes the universal concern of “No Child Left Behind.”

“I want to be known as the organization that’s working to close the achievement gap,” Mr. Weaver said, “that’s working to make sure every child has access to a great public school.”

Rear Guard

Some observers wonder whether the message discipline leaves room for even internal discussion of what it will take to make schools better. “I fear there’s little debate, substantive debate, about quality education and how to quantify it,” said a local NEA-paid union director who did not want to be named.

Others note that the NEA lags behind the AFT as a participant in the same discussions among policymakers and school advocates. Elected leaders in both the NEA and its state affiliates, many of whom have term limits, seem not to be in office long enough to take risks. Equally important, the power of some of the NEA’s large affiliates in labor strongholds such as California and New Jersey helps keeps the parent union wedded to worker rights over professional concerns. The 1.3 million-member AFT, in contrast, stays away from term limits and has few large state affiliates.

Many of the most talked-about school improvement ideas go against NEA policies or those of some of its most powerful affiliates: paying teachers more to teach some subjects than others, rewarding individual teachers for their students’ performance, toughening up the requirements for teacher tenure, reducing the prerogatives of seniority, establishing charter schools (unless they meet a long list of conditions), and giving out tuition vouchers.

“Rather than encouraging innovation, the NEA gives undue voice to its rear guard” through its structures and culture, Brad Jupp, a former union activist, wrote in an e-mail. As a member of the NEA-affiliated Denver Classroom Teachers Association, Mr. Jupp led an overhaul of Denver’s teacher-pay system that won approval from the local union, the school board, and voters. He now works as a senior adviser for the district.

Mike Antonucci, a teachers’ union watchdog who writes an online newsletter from his base in Elk Grove, Calif., contends that “the only reforms that come out of the unions are reforms that benefit the unions,” such as class-size reduction, which adds to the number of teachers who can be recruited.

Still, he acknowledged—echoing others—the AFT at least is more likely to take part in discussions about union power and school improvement.

“When they do show up, they are more likely to venture from ‘talking points’ than the NEA,” Mr. Antonucci added. “It’s very difficult to have a normal conversation about education because [NEA leaders] stick to the talking points.”

Balancing Act

At its most fundamental, the NEA is perennially in the position of weighing its members’ rights against the needs of public education, a dilemma that goes away only if you insist that teachers have no self-interest apart from children’s.

“It’s a real challenge for both teachers’ unions right now,” said Richard W. Hurd, an expert on public-sector and professional workers at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. “Some teachers feel under assault because of state testing and accountability, … and the NEA has to balance their current members’ interests with promoting the field of education.”

For instance, Mr. Hurd said, professional associations traditionally want to improve the quality of the current workforce through professional development. And yet in a fiscally cautious environment where many political forces remain hostile, pointing out the need for teachers to get better could pose a threat to their job security.

Thomas Toch, who covered education as a journalist for 25 years until he became a co-founder and co-director of the nonprofit think tank Education Sector, argues that with an impatient—if indebted— Democratic Party, the unions are running out of time to resolve the challenge in favor of education.

In the 1980s, he recalled, NEA leaders toyed with teacher-pay innovations similar to ones popular now. A union task force, for example, drafted a recommendation for diversifying teacher roles, giving the best people more responsibility and more pay. But a group led by then-executive-committee member John Wilson condemned the proposal as “hierarchical” and killed it.

“It’s very hard to change minds that have been forged in the crucible of hard-nosed collective bargaining and union organizing,” where solidarity is the first principle, said Mr. Toch, who worked for Education Week in the 1980s.

Some critics are even harsher. Martin Haberman, an expert on urban teaching, contends that the teachers’ unions are bound so tightly to an unimaginative view of members’ interests that they are unable to make any positive contribution.

“I don’t see either the NEA or the AFT as important participants in seeking to transform schools or to change them in any way that would have a salutary effect on student learning,” he charged in an e-mail.

Another Division

Union proponents, however, say that while there’s a struggle, the NEA has never been more conscious of its educational responsibility.

“I think that’s the great battle right now, between the professional-association side and the union side,” acknowledged Rhonda “Nikki” Barnes, the coordinator for black-community outreach at the NEA. ‘”We’re the offspring of both.”

But Ms. Barnes added that both the public and policymakers have to understand more about the complexities of the classroom if many of the proposed innovations are to work. In the meantime, the NEA has to fend off what would be harmful.

Said the nationally certified teacher: “We have to force people every day to deal with the complexities of teaching and learning, try to show the world what goes on in a classroom.”