For years, only a handful of the highest achievers graduated from high school with college courses on their transcripts. But as states strive to blur the line between high school graduation requirements and college expectations, such dual-enrollment courses are quickly becoming part of a broader strategy to help more students become college-ready.

Over the past decade, much of the attention to dual enrollment has focused on expansion and funding. Some individual programs—and increasingly, states—are working, however, to ensure that quality goes along with the proliferation. They want courses that are challenging enough to warrant college credit and that can effectively prepare students for higher education.

“It’s a real struggle. How do you expand access without diluting quality?” said Melinda Mechur Karp, a senior research associate at the Community College Research Center, based at Teachers College, Columbia University in New York City. “There’s some growing pains as [dual-enrollment options] go from small-scale to much more prominent and enthusiastically embraced programs.”

To help guide states’ efforts, policy experts have identified promising practices, beginning with an intensive and sustained collaboration between high schools and colleges on course content, standards, and pedagogy.

Read the accompanying story,

Such cooperation is at the heart of a set of accreditation standards for “concurrent enrollment” programs, or college courses delivered on high school campuses by high school teachers. The standards, which have recently been adopted by several states, were developed by the National Alliance of Concurrent Enrollment Programs, based in Syracuse, N.Y.

Courses that allow high school students to receive both high school and college credit simultaneously fall under the broad definition of dual enrollment. A number of different models fit the bill. In addition to concurrent enrollment, examples include tech-prep, which generally serves students in career and technical education, and early-college high schools, usually located on college campuses, which allow students to work toward an associate’s degree, or two years of college credit.

Dual-enrollment classes can be offered at colleges, taught by professors and attended by a mix of high school and college students. And many experts consider Advanced Placement courses a dual-enrollment option, since students who receive qualifying scores on the AP exams have the opportunity to earn college credit for courses taken in high school.

All these models have exploded in popularity in recent years, as policymakers and educators try to address worries about a lack of rigor and innovation at many high schools.

Colleges with dual-enrollment programs for at-risk high school students reported offering these types of extra help.

SOURCE: “Dual Enrollment of High School Students at Postsecondary Institutions: 2002-03,” National Center for Education Statistics

But concurrent-enrollment programs have proliferated the fastest. During the 2002-03 school year, there were approximately 1.2 million “enrollments” in dual-credit courses nationwide, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Of those, 74 percent were courses taught on a high school campus, according to the report, which contains the most recent data available on the topic.

Concurrent-enrollment programs are probably the most popular because they’re the cheapest and easiest to implement, policy experts say. But they’re also the programs that tend to prompt the most skepticism from policymakers and from colleges accepting credits.

“There’s very little accountability for these kinds of classes,” said Betsy Brand, the director of the American Youth Policy Forum, a research organization based in Washington that last year released an extensive study of accelerated-learning programs. “Nobody really knows what happens in them.”

That’s partly because most programs aren’t collecting much information on student outcomes, she said. An examination of accelerated-learning options, including concurrent enrollment, published in May 2006 by the Boulder, Colo.-based Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education reported that no data set provides state-by-state information about programs in a form that’s easy to analyze for trends, strengths, and weaknesses.

That lack of data is troubling to some higher education officials, who must decide whether to accept students’ credits, and to state lawmakers, who often control the purse strings for such programs. Some policy officials prefer Advanced Placement to other types of dual-enrollment options, since they believe its exams offer a built-in quality control. The New York City-based College Board, which sponsors the program, this year began to “audit” AP courses to make sure they meet rigorous standards.

“AP has a history. AP has a curriculum that’s well defined. AP has an assessment tool,” said Robert T. Tad Perry, the executive director of the South Dakota board of regents. “There’s no common standards for [concurrent]-enrollment courses. And there’s no common definition of what constitutes a college course.”

Last year, Mr. Perry audited his state’s concurrent-enrollment courses. Some classes had college-level expectations, he said, but other practices disturbed him. For instance, students taking concurrent-enrollment classes were mixed into classrooms with those taking the high school version of the course. And, he said, some of the supposed college-level courses used high school textbooks, materials, and assessments.

To address such criticisms, the National Association of Concurrent Enrollment Programs, known as NACEP, devised a set of accreditation standards for concurrent- enrollment programs.

Over the past year, at least four states—Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana, and Minnesota—have called for their programs to adopt those standards. Washington state has based its own guidelines on NACEP’s.

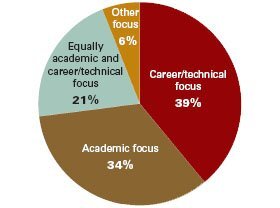

A nationally representative survey of colleges that offered dual-enrollment programs for at-risk high school students in the 2002-03 school year described them as having these primary missions.

SOURCE: “Dual Enrollment of High School Students at Postsecondary Institutions: 2002-03,” National Center for Education Statistics

Other states have policies in place aimed at making sure colleges carefully monitor any of their courses that are offered on high school campuses.

For instance, Florida, which operates a number of dual-enrollment programs primarily aimed at high and middle achievers, has regulations calling for colleges to treat concurrent-enrollment courses—and the high school educators who lead them—the same way they would any other course taught by an adjunct faculty member. Like Washington state, Florida relies on its regional accrediting agency to ensure that the high-school-based courses pass muster. NACEP’s standards aren’t necessarily geared to improving access for low-income students, which states are increasingly seeing as a potential mission for dual enrollment. But they do provide a blueprint to help high schools and colleges work closely on course content, assessments, and teaching methods.

Such give and take is critical to developing concurrent-enrollment and other dual-enrollment polices that can effectively use college-level work as “an apprenticeship of sorts” to help bridge the gap between high school and postsecondary education for all students, said Nancy Hoffman, a vice president at Jobs for the Future, a Boston-based research and advocacy organization.

Part of that process may involve professional development for high school teachers, to help them shift their instructional methods to more closely mirror college teaching.

“Norms are just as important as content,” said Ms. Mechur Karp of the Community College Research Center. For example, some college classes tend to involve fewer small-scale assignments and more independent learning than high school courses in the same subject. If possible, Ms. Mechur Karp said, high school teachers should be given time to observe instruction on the crediting college’s campus.

A 2006 report by the American Youth Policy Forum on accelerated-learning opportunities highlighted a variety of programs, including:

| Program | Washington State Running Start | Olive-Harvey Middle College High School |

|---|---|---|

| Students Served High, middle, low achievers; first-generation college; at-risk, and others. | High achievers | For low achievers who have officially withdrawn or been expelled from Chicago public high schools |

| Funding Cost to students | None for up to 18 credit hours per semester, but pay books, transportation costs | No cost to students |

Location | College classrooms and online courses | All classes on the community college’s campus |

| Prerequisites for Participation Tests or grades, recommedations, or interviews | Admissions requirement set by postsecondary institution | Must score at 8th grade levels in reading and math on admissions test; interview required |

| Program Length From one semester to up to five years | Open to high school juniors and seniors | Two to three years; students can enter in grades 10-12 |

| Faculty High school, college, or both | Faculty members at the college | Both high school and community college faculty members. Many classes are co-taught. |

| Extra Supports Designed to help students navigate the more-difficult coursework | None | Caring adults, academic assistance, safe environment, and peer network. |

| Regulatory Framework Promoted by state; funding sources | Dual-enrollment mandated by state’s Learning by Choice law. Colleges bill districts, which can keep 7 percent for administrative costs. | Has charter school status and funding; receives additional money from state Department of Children and Family Services and Illinois Board of Education. |

SOURCE: “The College Ladder, Linking Secondary and Postsecondary Education for All Students,” American Youth Policy Forum

To help students tackle these new expectations, experts also stress that all types of dual-enrollment programs—and particularly those aimed at students who might not consider themselves college material— should incorporate extra supports, such as counseling, tutoring, and help with study skills.

“There are certain things a program should offer,” Ms. Brand said. “If it’s just an education class without any other supports, then students probably aren’t going to be as successful.”

If possible, the programs should expose students to college life through campus visits and opportunities to use campus facilities, such as libraries and labs.

Not all students who can benefit from college courses are prepared to handle them, at least initially. Policy experts recommend that programs carefully sequence coursework so that students aren’t simply thrown into a college course without the proper preparation or context.

College Now, a City University of New York-operated program offered on both high school and college campuses, serving students at nearly every high school in the 1.1 million-student New York City system, requires that students receive certain scores on state mathematics and language arts tests before they’re allowed to take college-credit courses.

Students who aren’t ready for those classes have access to noncredit “foundation courses,” usually offered on college campuses, that are intended to help prepare them for college-level coursework in an area of interest.

“We work very closely with college faculty on what they think students should come in knowing,” said Eric Hofmann, the associate director of College Now. “It’s not about the content they have to cover, since it’s not for college credit. What we want them to do is slow down and get deeper into discipline-based skills.”

For instance, he said, a foundation course in history could show students how to analyze primary-source documents in an historical context.

A handful of states are beginning to pay attention to the features associated with high-quality programs as they expand their dual-enrollment options. At least nine states—Florida, Maine, Minnesota, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Rhode Island, Utah, and Virginia—have or are contemplating policies to make “the attainment of college credit in high school an opportunity, or even a requirement, for all students,” according to an article by Ms. Hoffman set to appear in Minding the Gap: Why Integrating High School With College Makes Sense and How to Do It, to be published this fall by Harvard Education Publishing Group.

Rhode Island is working with Jobs for the Future on a proposal to expand high-quality dual-credit options, with the goal of giving every student the opportunity to receive substantial college credit before graduating from high school.

In a draft report released last year, the organization urged Rhode Island to establish a data system to carefully track student characteristics and program outcomes, such as whether students who took dual-credit courses are more likely to enroll in college than similar students who did not.

Colleges should review portfolios of student work to make sure grading and expectations are comparable, Jobs for the Future suggested. The state should also periodically audit student work for courses taught on high school campuses, the organization’s draft report recommended.

“Course titles can create false promises,” said Todd D. Flaherty, a deputy state commissioner of education in Rhode Island. “We want to get kids into college-prep courses that are indeed college-prep.”