New reports looking at how the teacher-quality provisions of the No Child Left Behind Act are playing out in the nation’s classrooms suggest that, while compliance with the 5½-year-old federal law is widespread, problems and inequities persist and, in the end, labeling a teacher “highly qualified” is no guarantee of effectiveness.

“I think the high compliance rate suggests there were states that set the bar low and, in a way, grandfathered in a lot of teachers,” said Kerstin Carlson Lefloch, a primary author of “Teacher Quality Under NCLB: Interim Report,” a large-scale study released last week by the U.S. Department of Education. “To get to the real story, you have to look below the surface, and that’s where we’re still seeing variation and still seeing inequities.”

Under the wide-ranging federal law, which is up for congressional reauthorization, states had until the end of this past school year to ensure that they were staffing 100 percent of their core academic classes with highly qualified teachers. Such teachers are defined as those who have a bachelor’s degree, are fully certified, and can show mastery of the subjects they teach, either by completing coursework, passing state subject-matter tests, or meeting some other state-set criteria.

By the close of the 2005-06 year, no state had hit the 100 percent mark, according to the Education Department’s latest tally of state reports, which came out in July. On average, states reported that highly qualified teachers were teaching 92 percent of the classes that the law targets that year.

In a July 23 letter to chief state school officers, U.S. Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings said the department would continue its policy of not penalizing states that fell short of 100 percent as long as they were making “good faith” efforts to follow the law.

The studies trickling out now find relatively high compliance rates in schools and districts, as well as in states. Though based on surveys from the 2004-05 school year, Ms. LeFloch’s report suggests that 90 percent of teachers met their states’ “highly qualified” definition, whether they knew it or not. Nearly a quarter of the teachers did not know their status under the law.

Conducted for the department by the Washington-based American Institutes for Research and the RAND Corp. of Santa Monica, Calif., that report drew on surveys of nearly 13,000 teachers, special educators, paraprofessionals, and administrators in 300 districts across the country.

Another survey, this one taken over the 2006-07 school year and published Aug. 22 by the Center on Education Policy, found 83 percent of 342 districts reporting that they either were already in full compliance with the law or they expected to be by summer vacation. (“NCLB ‘Highly Qualified’ Rules for Teachers Seen as Ineffective,” Aug. 29, 2007.)

The Washington-based research and advocacy group also turned up spottier levels of compliance at the state level, though. Officials in 17 of the 50 states polled said they expected to reach their federal teacher-quality targets by this past June—a lower level than states’ official reports to the federal government would suggest.

Standards Vary

States were still having some problems, though, in developing the data systems they needed to accurately determine teachers’ job qualifications and report to parents when their children were being taught by teachers who fall short of that mark, according to the CEP and the AIR-RAND reports.

Also, despite the seemingly widespread attempts to follow the law, the two reports and the Education Department’s figures found that highly qualified teachers were harder to find in some categories and settings than in others. Chief among those areas are special education and instruction of English-language learners; secondary school mathematics and sciences classes; and middle schools, rural schools, and schools with high percentages of children from low-income families and minority students.

Some districts, in fact, faced a double whammy in that regard, researchers said. In the AIR/RAND study, for example, researchers said the percentage of high-minority districts that struggled to attract and retain highly qualified applicants was nearly double that of districts with low-minority enrollments. And a higher proportion of those disadvantaged districts were offering financial incentives and alternative-certification options to attract teachers to their schools—sometimes in competition with other schools and districts in similar straits, the AIR-RAND study notes.

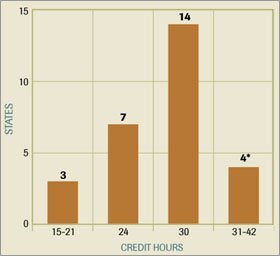

States vary in the amount of subject-matter coursework they consider equivalent to a college major in order for new secondary teachers to meet the content-mastery requirements under the No Child Left Behind Act.

NOTE: These data, from 2004-05, are based on the 27 states and the District of Columbia whose guidelines for “highly qualified” teachers specified the number of hours equivalent to a major.

* Indicates that the District of Columbia is included.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education

That study also found, however, that state policies for determining what counts as highly qualified vary widely from state to state. For instance, although all but two states had tests of teachers’ content knowledge in place three years after the passage of the NCLB law, the minimum passing scores spanned a wide range. On the Praxis II teacher test in middle school mathematics, for example, the cutoff ranged from 139 of a maximum score of 200 in South Dakota to 163 in Virginia.

The researchers also found that 47 states had adopted an option under the law—known as the High Objective Uniform State Standard of Evaluation, or HOUSSE provision—that allows them to set their own criteria for determining whether teachers already on the job met the highly qualified standard. The standards differ from state to state in the degree to which teachers get credit for their years on the job vs. credit for measures aimed more directly at assessing their knowledge and practical skills.

One result of that state-to-state variation: “Highly qualified” often meant something different in schools where a high percentage of students were poor than it did in better-off schools.

In the former group, the report found, “highly qualified teachers” tended to be less experienced and less likely to have a degree in the subjects they taught than such teachers in more affluent schools.

“The AIR-RAND report very clearly shows that the federal government has given very poor direction and a variety of mixed signals to states on a whole range of highly qualified teacher provisions,” said Barnett Berry, the president of the Center for Teaching Quality, a research and advocacy group based in Hillsborough, N.C. Rural schools, in particular, needed more resources to attract skilled teachers and boost the subject-matter expertise of existing teachers, he added.

Wrong Criteria?

But Robert C. Pianta, the dean of the education school at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, said the variation the researchers found might also suggest that federal policymakers are measuring teacher quality the wrong way.

“If almost everybody is already meeting those standards, and we’re still not seeing large achievement gains, then that should give us pause as to whether or not we’re using the right metrics,” Mr. Pianta said in an interview.

For a study published in March in the journal Science, Mr. Pianta and his research partners conducted detailed observations of 5th grade teachers in 20 states. They found that teachers who were labeled “highly qualified” were no more likely than colleagues without that designation to use effective teaching practices. (“Study Casts Doubt on Value of ‘Highly Qualified’ Status,” April 4, 2007.)

Mr. Pianta favors rating teachers on the extent to which they use education practices proven to be scientifically sound as a measure of their highly qualified status.

In the CEP’s surveys of the administrators in charge of implementing NCLB’s teacher-quality provisions in 50 states and 349 districts, those officials called the highly-qualified-teacher definition’s focus on content knowledge “too narrow” for accurately identifying good teachers.

“Some of them say whether teachers like kids and can improve the skills of diverse students also are important,” explained Jack Jennings, CEP’s president and chief executive officer. “But that’s hard to measure.”

Other critics, most notably the Commission on No Child Left Behind, a bipartisan panel formed by the Washington-based Aspen Institute to make recommendations for improving the law, would use analyses of student gains on state tests to determine teachers’ highly qualified status.

No study has yet determined whether students learn more from teachers deemed to be “highly qualified” under the current law. In the CEP report, most administrators expressed skepticism that the law had led to student-achievement gains in their schools.

“That’s the big question out there,” said the AIR’s Ms. LeFloch, and one that neither the AIR-RAND nor the CEP study was designed to address.

That AIR-RAND study also found that, while nearly all teachers took part over the 2004-05 school year in the kind of content-focused professional development in reading and mathematics that the federal law promotes, only one-fifth of them had received 24 hours or more of training—the equivalent of a one-week in-service program. Instead, most teachers’ training had totaled six hours or fewer for that year.

The new studies are timely, coming as congressional leaders begin to float ideas for revising the NCLB law. A draft reauthorization plan released last week by House education committee leaders put forth no major proposals for improving the teacher-quality provisions, but U.S. Rep. George Miller, the California Democrat who chairs that committee, said such plans are forthcoming.