Though education experts, business leaders, and government officials have largely embraced the drive to raise the level of math and science courses, students and parents may be satisfied with a less rigorous level of instruction in those subjects.

That’s the conclusion of a new study of the views of parents and students in Kansas and Missouri by the New York City-based research organization Public Agenda, which found a degree of contentment with current math and science curricula that contrasts sharply with the dissatisfaction expressed by leaders and educators at the national level.

| A Search for Answers in Science and Math | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

“What we found when we looked at the views of parents and students was much, much less urgency,” said Jean Johnson, an executive vice president and the director of education insights at Public Agenda.

In the past few years, corporate leaders have stepped up their complaints about the state of math and science education, and federal lawmakers have ratcheted up their efforts to use legislation to force improvements. Last month, for example, President Bush signed into a law a bill that, among other measures, pushes for improved teacher recruitment and training to bolster math and science education through the use of federal grants.

But that heightened concern has not reached parents and students, says the report, “Important, But Not for Me: Parents and Students in Kansas and Missouri Talk About Math, Science, and Technology Education.”

‘Fine as They Are’

Released Sept. 19, the study involved a phone survey of 2,767 students and parents of public school children in grades 6-12 in the two states, with a special emphasis on the Kansas City area.

A study on the views of secondary-school students and their parents in Kansas and Missouri found that they feel less urgency about mastering high-level math and science than business leaders and experts say they should.

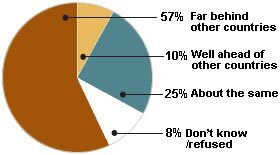

Most parents recognize that the United States is behind other countries in math, science, and technology education.

As far as you know, do you think that the U.S. is well ahead of other industrialized countries when it comes to educating its young people in science and math?

While most parents see basic math as “absolutely essential,” relatively few see advanced science and math in the same light.

Do you think the following is essential for schools to teach students before they’re done with high school and go out into the real world?

Percent who say:

SOURCE: Public Agenda

Overall, only 25 percent of parents think their children should be studying more math and science, and 70 percent say things “are fine as they are now,” the study found.

However, minority parents were less satisfied with the math and science education their children received. For example, 65 percent of African-American parents and 61 percent of Hispanic parents said today’s students are not really learning basic math, compared with 42 percent of white parents.

Among students, 72 percent said all students should not be expected to take advanced science courses such as physics or advanced chemistry.

“There is room for concern here,” said Jodi Peterson, the assistant executive director of legislative and public affairs for the National Science Teachers Association, based in Arlington, Va.

Ms. Peterson cautioned that the survey was limited geographically and results might differ in other places. Still, she added: “We have a big challenge ahead to educate parents as to why math and science is important for their kids.”

The survey found that parents believe math and science education is rigorous, Ms. Johnson said, because they see their children doing more-challenging lessons than they did in school. Sixty-nine percent of parents said math is harder today, while 51 percent said science is harder than in their own youth.

Both parents and students say basic math and science is critically important, though, with nine in 10 people surveyed calling it essential; 79 percent of parents and 70 percent of students also said algebra is essential.

Knowledge Opens Doors

Margo Quiriconi, the director of education research and policy at the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, the Kansas City, Mo.-based philanthropy that provided funding for the project, said students need to understand that a good grounding in math and science can lead them into high-tech companies in many fields, including the animal sciences industry, which has roots in Kansas City.

“We need a workforce able to support that generation of new companies,” Ms. Quiriconi said. The Kauffman Foundation runs a program in five counties in the Kansas City region to improve math, science, and technology education. The foundation also provides funding to Education Week for coverage of those subjects.

Francis “Skip” Fennell, the president of the Reston, Va.-based National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, said teachers must help students understand where intense study of advanced math and science can lead them, such as to jobs with annual starting salaries above $75,000, for example.

“Students need to know that knowledge of this subject really opens doors,” he said.

A majority of parents surveyed said their children’s teachers make math and science relevant in the real world. Only 20 percent of students blamed poor teaching for students who do not achieve in math and science courses.

One bright spot in the survey: Eighty-five percent of students said they believe students can learn math and science if they spend the time, instead of seeing such achievement as simply a result of innate aptitude.