Stanford University psychologist Claude M. Steele made headlines in 1995 with a study that introduced the phrase “stereotype threat” into the national lexicon. Put simply, it’s the idea that people tend to underperform when confronted with situations that might confirm negative stereotypes about their social group.

Mr. Steele’s original research involved black college students whose test performance faltered when they were told they were taking an exam that would measure intellectual ability. But the effect has since been documented in more than 200 studies involving all sorts of situations.

Scholars have found evidence of “stereotype threat” occurring, for example, among elementary school girls taking mathematics tests, elderly people given a memory test, and white men being assessed on athletic ability. Even something as subtle as asking students to indicate their race or gender on a test form can trigger the phenomenon, some of those studies have suggested.

Now comes a new line of research aimed at figuring out what to do about the problem. Focusing mostly on middle schools, the second generation of work is starting to point to tools and techniques that show promise in countering stereotype threat in the classroom and improving the academic achievement of students who are most likely to suffer from its effects, such as African-Americans, Latinos, and girls.

Narrowing Gaps

The hope is that such interventions might one day narrow persistent achievement gaps between many minority students and their higher-achieving white and Asian American peers, and expand the ranks of young women who pursue high-level studies in mathematics and science.

“You can scare people so much in the lab that you can make existing gaps wider,” said Joshua Aronson, an associate professor of applied psychology at New York University, who is conducting much of that research. “But the real message of this work is that you also can make the gaps narrower.”

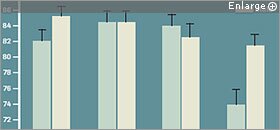

Four groups of 7th graders received different messages in a Male Texas study to test efforts to ease the effect of “stereotype threat” on students’ test scores. The first group (labeled incremental) was told that intelligence is not fixed but can grow with mental work. The second (attribution) heard that difficulties at the start of middle school were to be expected. The third received a mix of those two messages, and the fourth, serving as a control group, learned of the dangers of drugs. Girls’ scores in the first three groups were all higher than those of girls in the control group.

SOURCE: Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology

Mr. Aronson was the co-author, with Mr. Steele, of the study that propelled the “stereotype threat” idea into the national achievement-gap discussion more than a decade ago.

In that experiment, the researchers divided black and white Stanford undergraduates into two groups and gave each group the same test. One group got the message that the test had IQ-like diagnostic properties; the other group was told that the test did not measure intellectual ability.

The African-Americans in the group performed dramatically better in the latter situation, while white students performed equally well under both conditions. Mr. Steele and his colleagues contend the black students tested badly in the first instance because they feared their poor performance would confirm a stereotype that blacks were intellectually inferior.

Few groups, though, seem to be immune from stereotype threat. Mr. Aronson found in a 1999 study, for instance, that he could induce the same sort of effect in white male engineering and math majors with “astronomical” SAT scores simply by telling them that scores from their laboratory tests would be used to study Asian students’ apparent superiority in mathematics.

Faced with the risk of confirming a negative stereotype about themselves, students react in different ways, according to researchers. While some underperform, others redouble their efforts.

Most worrisome, though, is the large number of students from vulnerable groups who, over time, begin to avoid situations that seem potentially threatening. In one of Mr. Aronson’s experiments with middle schoolers, for example, Latino students—but not non-Hispanic white students—chose easier problems when they understood that the test they were taking measured mathematical ability.

“I think we need to worry about how students’ vulnerability can lead to real differences in ability,” said Mr. Aronson. “As students shy away from those things that could make them smarter, it becomes sort of a negative spiral.”

“We think middle school is when problems emerge,” he added, “and when you see minority kids start to disengage and girls start to get anxious about math.”

Messages on Intelligence

To head off such outcomes, Mr. Aronson and other scholars drew on research begun in the early 1980s by Carol S. Dweck, who is now a Stanford University psychologist. Across the board, she has found, students are more motivated to achieve when they believe that intelligence is malleable, rather than a trait that is fixed at birth, and that, with a little hard work, they, too, could improve their grades.

With Catherine Good, an assistant professor of psychology at New York City’s Baruch College, Mr. Aronson assigned college-student mentors to three groups of 7th graders from a Texas school district with high concentrations of poor and minority students.

In one of the groups, the mentors conveyed the idea that intelligence could be improved and expanded. The second group of students was told that the learning difficulties they faced in their first year of middle school were a normal part of the transition process.

The mentors gave students in the third group an anti-drug message. While reading scores improved for all three groups by the end of the school year, the improvements for the students in the first two groups were dramatically higher than for the group that received the anti-drug message, which served as the control group.

In math, girls improved at an especially fast clip in the first two groups. Their gains were large enough, in fact, to essentially bridge the achievement gap that once separated them from their higher-performing male counterparts.

Since that 2003 study, Ms. Good and Ms. Dweck have also begun to explore the role that learning environments play in conveying subtle messages about the nature of intelligence and how that role affects girls’ math achievement.

“When students perceive their learning environment to convey a fixed view of intelligence, their achievement goes down,” Ms. Good said.

She said teachers may inadvertently impart that message when they praise students for being “smart,” rather than for working hard, or give the impression that math geniuses developed famous theorems and formulas almost instantly, rather than laboring over them for years.

“If we can get teachers to create learning environments that convey this incremental view of intelligence, then stereotype threats don’t have much power,” Ms. Good said. Though those studies are not yet published, Ms. Good has begun to share her findings with teachers in Montclair, N.J., and other districts eager to boost minority achievement.

In another intervention, Geoffrey L. Cohen, a psychology professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder, found that having 7th graders write for 15 minutes, several times a year, on the values they cherish seemed to shrink achievement gaps by as much as much as 40 percent over the course of a school year. (“Writing About Values Found to Shrink Achievement Gap,” Sept. 6, 2006.)

While the dramatic results have prompted some skepticism, Mr. Cohen has so far replicated his findings with two other cohorts of students.

“What we think is going on is there’s this recursive cycle,” Mr. Cohen said. “If students do a little better as a result of this self-affirmation, that’s an affirmation in itself.”

“It also seems to reduce the extent to which kids are thinking about race,” added Mr. Cohen, who tested that theory by giving students lists of word fragments that could be completed in ways that carried racial connotations or not.

‘Dramatic Insights’ Foreseen

Meanwhile, Claude Steele himself, working in conjunction with his wife, Dorothy Steele, a scholar of early-childhood education, has begun studying the practices used by California elementary and middle school teachers in classrooms where achievement gaps are small.

“I’m heartened by all the things that seem to work,” he said of the work by his colleagues, many of whom are former graduate students. “This is a generation of highly skilled social scientists, and I think there will be some dramatic insights within the next five years into how we can counter stereotype threat in the classroom.”

Scholars agree, however, that eliminating stereotype threat will not completely close achievement gaps. To do that, Ms. Good, Mr. Aronson, and others have been recruited to be part of cross-disciplinary research teams working on an all-out assault on the problem.

The largest of those efforts is a multistate project launched under the auspices of the Strategic Education Research Partnership or SERP, an independent national group based in Washington. (“Real-World Problems Inspire R&D Solutions Geared to Classroom,” Oct. 10, 2007.)

In Montclair, Evanston, Ill., Fremont, Calif., and dozens of other districts, the SERP researchers are testing a three-week summer program for low-achieving minority students that is aimed at grooming them to see themselves as a community of math scholars.

Through the program, called Academic Youth Development, students learn how the brain grows and changes as new information is acquired. They also get lessons in particular aspects of math, such as problem-solving and proportional reasoning. Later on, they take accelerated math classes that enable them to catch up to higher-achieving peers.

“It has to go hand in hand,” said Uri Treisman, who is spearheading that effort. A math professor, he founded and directs the Charles A. Dana Center at the University of Texas at Austin. “You cannot help kids learn algebra with psychology alone. By the same token, many people look at this and say, ‘The math is great,’ so they give kids harder math without the psychology. That doesn’t work either.”