A much-anticipated commercial computer game about evolution is getting a favorable response from some scholars, who welcome its interactive, engaging approach to the topic even though a few of its features sacrifice strict scientific accuracy to fun.

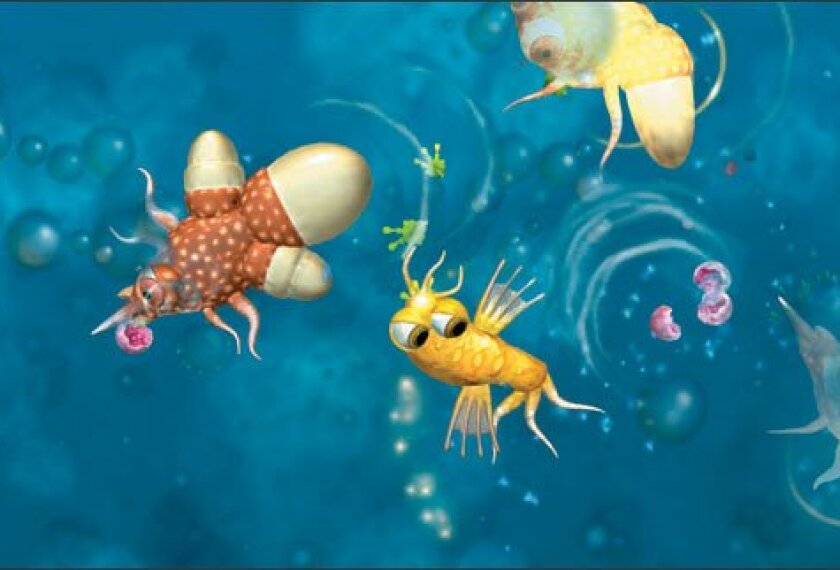

The game, called Spore, was released in stores across the United States last week. It gives users the ability to “evolve life,” or customize creatures by giving them traits that affect their ability to survive and prosper, as well as share their creations with a vast network of other game players.

Debates over how to teach about evolution, a foundational theory in the study of biology, have raged in schools for years. For a number of academic experts familiar with those debates who had heard of Spore or seen demonstrations of it, the game is a clever way to raise students’ interest in evolution.

But they also said that the game’s primary benefits were probably recreational, rather than educational, given some of the liberties it takes with the science of evolution.

Computer games like Spore “are a natural place for students to gravitate to,” said Joe Meert, an associate professor of geology at the University of Florida, in Gainesville, who covers evolution in his classes. He is a member of Florida Citizens for Science, a group that has supported the teaching of evolution in public schools and opposed what it regards as unscientific alternatives to it.

“Even the things that it gets wrong, it could be a teachable moment,” Mr. Meert said. “Here’s something the game gets wrong. Why is it wrong?”

Spore was designed by Will Wright, know for having previously created popular games such as SimCity, which allows users to build and plan imaginary cities. The company that produced Spore, Electronic Arts, or EA, of Redwood City, Calif., describes the new game as a “personal universe in a box.”

The game allows users to create living things, from their inception as “pond scum” to fully evolved beings, by choosing advantageous features. Players can also build civilizations and entire worlds.

The theory of evolution, advanced most famously by Charles Darwin, posits that humans and other living things have evolved over millions of years through the process of natural selection —basically, survival of the fittest —along with random mutation.

In allowing students to control how a creature evolves, Spore employs a process of “external manipulation” that mainstream scientists would reject as unscientific, said Barbara Forrest, a professor of philosophy at Southeastern Louisiana University, in Hammond, who has written extensively about the history of evolution study. For instance, the scientific consensus is that “intelligent design,” or the idea that features of living things show signs of having been created by a master hand, is religion, not science.

Visual Learning

Even so, Spore could bolster some students’ interest in the topic of evolution, Ms. Forrest said. Many students, even at the college level, tend to respond better to instruction about the theory when lessons are presented visually, rather than simply through written text or in lectures, she said. That is partly because evolution plays out over thousands or millions of years, and because it does not lend itself to simple hands-on activities and lessons.

To present evolution visually, Ms. Forrest has used a television program that includes displays of the evolutionary process. The program, “Judgment Day,” focuses on the landmark 2005 federal court trial on whether intelligent design could be taught as science in public school science classes. (“‘Intelligent Design’ Goes on Trial in Pa.,” Oct. 5, 2005.) Ms. Forrest testified in that trial that intelligent design had links to biblically based creationism.

A game like Spore “is not a substitute for learning science directly,” she said. Yet “having taught students about evolution,” she argues that “visuals are very important.”

While Mr. Wright and others who worked on Spore were inspired by science and attempted to stay true to it whenever possible, they also strayed from scientific principles to allow for player creativity and to avoid being “pedantic,” said Lucy Bradshaw, the executive producer of Spore.

“It’s very much a game,” Ms. Bradshaw said, but one that nonetheless gets at “scientific processes that drive the ecosystem.”

When most game developers have to choose between presenting completely accurate material and making their games fun, they choose fun, said Christopher Dede, a professor of learning technologies at Harvard University.

Mr. Dede said the educational value of games depends on how accurately they present academic ideas in science or other subjects.