Once fuel for mass book burnings, comic books are gaining a foothold in the nation’s schools, with teachers seeing them as a learning tool and scholars viewing them as a promising subject for educational research.

Evidence of the rising credibility of Spiderman, Batman, and Archie came last month when Fordham University’s graduate school of education in New York City hosted what was billed as the first academic conference on “Graphica in Education.” The Jan. 28 event drew 125 teachers, scholars, artists, and publishers from across the country and featured presentations on everything from “aesthetics of action heroes” to “critical literacy and graphic novels in the classroom.”

“There’s more research out there than people seem to recognize,” said James “Bucky” Carter, an assistant professor of English education at the University of Texas at El Paso and a keynote speaker for the event. “And there are multiple studies to suggest that students who read comics go on to read more, and to read more varied literature.”

The term “graphica” takes in “manga,” which are Japanese-style graphic novels; “art graphic novels,” which refer to both fiction and nonfiction literary works that blend visuals and text; and more traditional comic books of the X-Men variety.

The academic interest comes as sales of graphic literature are exploding worldwide, and libraries and book stores in the United States are setting aside sections to display it.

“If you look at the literature, some of these books are quite good,” said Marshall A. George, the conference organizer and an associate professor of English and literacy at Fordham. One notable example is Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, in which the author describes his father’s experiences during the Holocaust. It won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992.

Still, proponents of the educational uses of comics admit that the medium retains a bit of a stigma among educators, some of whom see the books as “subliterature.” Even some students still sniff at the idea. Heidi Hammond, a Minnesota high school librarian, said one of her students characterized the medium as something for immature adults “who still live in their parents’ basement and eat Hot Pockets.”

But the supporters don’t necessarily argue that graphica should replace literary classics, either. Instead, teachers can use graphic representations of Shakespearean plays, Beowulf, and other works to help students make a transition to the real thing.

“As we become a more and more visual society, schools will recognize the usefulness of these novels,” said Stephen Weiner, the director of the Maynard Public Library in Maynard, Mass., and the author of two books on graphic literature. “And the more teachers adapt to it, the better the response they’ll get from students.”

Manga Multipurposed

The nascent body of educational research on comics, while mostly anecdotal at this point, doesn’t indicate their prevalence in classrooms. The studies do suggest, however, that educators are using the medium for a variety of purposes, including as a bridge to full literacy for English-language learners and struggling readers; a tool for discussing sensitive social issues; a subject for lessons on visual literacy; a vehicle for ethics discussion in classes with gifted students; and a means for nurturing creativity in after-school programs.

In 2004, state educators in Maryland—with help from the Timonium, Md.-based Diamond Comics Distributors and Disney Publishing Worldwide in Burbank, Calif.—launched what is believed to be the first statewide program to promote the use of comics in schools. Last spring, 3rd grade teachers in 80 Maryland schools used books and lesson plans developed through the state’s Comic Book Initiative, according to Darla Strouse, the project director.

“It’s getting on educators’ radars,” said Michael Bitz, who founded an after-school program called the Comic Book Project, in which students create comics. He is also an assistant professor of teacher education at Ramapo College of New Jersey in Mahwah and a fellow at the Mind Trust, an Indianapolis-based nonprofit group that encourages entrepreneurship in education. “And librarians really led the way for schools,” Mr. Bitz added.

Irony and ‘Emanata’

That was the case at the 1,532-student Henry Sibley High School in Mendota Heights, Minn., where Ms. Hammond began stocking graphic novels and manga in the library six years ago.

When she noticed that students weren’t checking out the graphic novels, Ms. Hammond, who is also an adjunct professor of young adult literature at the College of St. Catherine in nearby St. Paul, undertook her own study looking at how students new to the novels would respond to lessons that incorporate them.

She chose American Born Chinese, an award-winning graphic novel that explores racism and immigration, and guest-taught it in a 12th grade political science class. Only a fourth of the 23 students had read a graphic novel previously, Ms. Hammond said.

“They responded very similarly to the way they would respond to traditional literature,” she said.

Ms. Hammond taught the students about graphic-novel conventions, such as the use of “emanata,” which are symbols like light bulbs, hearts, or sweat droplets that convey meaning, and asked the students to re-read the text. She said students reported noticing more visual details on the second read.

Mr. Carter said the new interest in comics among educators marks a turnaround from the late 1940s, when psychiatrist Fredric Wertham warned that comics would have a harmful psychological effect on children. His writings prompted parents, educators, and clergy in a handful of U.S. communities to stage comic-book burnings into the mid-1950s.

Measuring the Benefits

Later studies cast the medium in a more positive light. In a 1996 study, for example, Stephen D. Krashen, a professor emeritus of education at the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles, and a colleague found that 7th grade boys who were avid comics readers also tended to read more books, regardless of whether they were middle-class, suburban students or low-income students from an inner-city school.

Also, while comics vary in readability, Mr. Krashen said, some studies suggest that they use more rare words—such as “debacle” or “synaptic”—than traditional children’s books.

Still, while such prominent leaders as Archbishop Desmond Tutu and President Barack Obama credit comic books with awakening their own love of reading, research has yet to provide definitive proof that reading comics makes students better readers or causes them to learn more, said Mr. Bitz, the Comic Book Project’s founding director.

Launched in 2001 in New York City, the project engages disadvantaged students in creating their own comic books through after-school clubs and programs. It now operates in nearly a dozen cities, including Chicago, St. Louis, San Francisco, Tucson, and Washington.

Mr. Bitz said his own studies of the project show that “in the process of creating comics, students are extending literary pathways that, in the end, address the basic literacy concepts we’re all trying to get at.” They learn and practice spelling and grammar, for example.

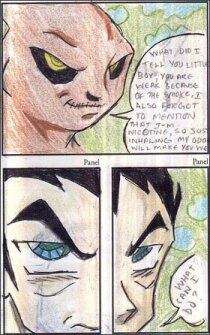

He also found that, rather than focus on superheroes or faraway planets, students’ creations reflected their own lives. Participants designed comics about gang violence, relations with the opposite sex, and drug abuse, and they chose as their settings street corners and schoolyards.

Students also practiced democracy, Mr. Bitz said, as they collaborated in the creative process.