For decades, when elected officials, researchers, educators, and parents have wanted a clear-eyed measure of what students know in a range of subjects, they have turned to an authoritative source: the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

Now the country stands poised to enter a new testing era. All but two states have agreed to work toward creating common academic standards, with the eventual goal of establishing common assessments.

Which leads to an obvious question: What will become of NAEP?

Some say the federally sponsored program is unlikely to change as a result of the ongoing standards and assessment project. Others say that until more is known about the structure and schedule of common state tests, it’s difficult to predict whether NAEP’s role will grow or shrink.

SOURCE: Institute of Education Sciences

“There’s nothing in this project that would put the NAEP out of business,” said Gary W. Phillips, a vice president and chief scientist at the Washington-based American Institutes for Research. “There’s no way a bottoms-up test could do what the NAEP is built to do, every day.”

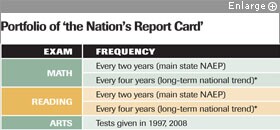

Established in 1969, NAEP, often called “the nation’s report card,” is the only continuous, nationally representative test of what students know in various subjects. It measures how national student performance has changed over time, with reading and mathematics scores dating back to the 1970s. It also tests students in arts, civics, economics, geography, U.S. history, science, and writing.

And it allows state-by-state comparisons of student reading and math performance every two years, scores that receive widespread attention.

Above all, the national assessment serves a truth-telling function. When individual states report big gains or declines in student scores on their own tests, NAEP offers an independent, though not necessarily perfect, point of comparison.

State Work Under Way

Within a few years, however, states could have a new set of tests to use in judging student performance in reading and math.

The Council of Chief State School Officers and the National Governors Association have, over the past year, launched a venture known as the Common Core State Standards Initiative, aimed at establishing common academic expectations as an alternative to varying state standards.

Draft college- and workforce-readiness standards were produced this fall in reading and math, and K-12 standards are in the works. The groups’ hope is that the standards become the basis for common reading and math tests within three years.

Dane Linn, the director of education for the NGA’s Center for Best Practices, said common-core organizers are still thinking through how their work relates to NAEP. But all indications suggest there will be a great need for the national assessment, even if shared standards and tests take hold, he said.

“You do need some external benchmarks against even state common assessments,” said Mr. Linn, who added: “I don’t think [NAEP] should go away.”

The future role of NAEP will likely hinge on what the future common assessments look like, several observers say.

Despite states’ movement on common standards, for instance, it’s unclear how many will agree to adopt a single, common assessment. Some predict states will accept common standards and assessments incrementally. Others say different consortia of states—10, 15, or more of them—could band together to craft their own exams, based on the common standards.

In any of those scenarios, NAEP would continue to provide an important “external metric” for judging the performance of states, or groups of them—including those that opt out of common standards and exams entirely, argued Chester E. Finn, the president of the Washington-based Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

“In the real world we inherit, it will be a very long time before all 50 states participate in a common test,” Mr. Finn said. It may be that a state that “does things its own way” ends up performing better on NAEP, he said, and “if so, you’d want to know that.”

‘Independent Verifier’

Another unresolved question: Participating common-core states are expected to align their standards within an 85 percent match of the final reading and math ones. If the remaining 15 percent would substantially alter the content of state standards and tests, NAEP would presumably be a good external measure of them, said Cornelia S. Orr, the executive director of the National Assessment Governing Board, the independent panel that sets policy for NAEP.

One of NAEP’s many strengths is that it provides precious long-term-trend results on students performance nationwide, said Mr. Phillips, a former acting commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, which administers NAEP.

State tests produce scores for individual students and schools, and common-core assessments would presumably do the same, Mr. Phillips said. NAEP is forbidden by federal law from doing that. But its use of representative sampling and other sophisticated methodology produces more precise information across student groups on academic performance, achievement gaps, and students’ content knowledge than state tests do, Mr. Phillips said. NAEP results can also be linked to large-scale collections of federal data, a powerful research tool.

In states with low NAEP scores, officials sometimes attribute poor performance to their state exams’ covering different content from NAEP. But those differences also make NAEP important, some say: It reveals what a state’s students know when they’re judged on different academic material.

One of the biggest wild cards with common assessments and NAEP is whether states would agree to use common “performance standards”—uniform measures for judging whether students are proficient or struggling academically. Those benchmarks could be produced by using common cutoff scores on tests across states.

If states were unwilling to do that, then NAEP, which reports student scores in three main achievement categories—“basic,” “proficient,” and “advanced,” in addition to “below basic”—would remain as an “independent verifier,” said Gregory J. Cizek, a professor of educational measurement and evaluation at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“If you can’t get people to buy in to common performance standards, then there’s a role for the NAEP,” said Mr. Cizek, who recently ended a term on NAGB.

While the NGA’s Mr. Linn said that he believes it is important to reduce the discrepancies in how states set proficiency standards, he added that common-core organizers and states officials are a long way from making a decision about performance benchmarks.

New Role for NAGB?

In addition, common-core officials have barely begun to discuss standards and tests in subjects

other than reading and math. That means NAEP, with its broad menu of subject-matter tests, is likely to remain relevant for the foreseeable future, Mr. Cizek argued.

Whatever becomes of NAEP, policymakers should consider giving the 26-member governing board a direct role in the common-core undertaking, said Mr. Finn, a former NAGB chairman. The project will eventually need a more permanent organization to oversee and revise common standards and assessments, and Mr. Finn believes NAGB could fill that role.

Others question the feasibility of such a change. Mr. Cizek said it could transform NAGB into more of a “political entity.” While governing-board members are appointed by the secretary of education, NAGB was was established in 1988 by Congress as independent of both the agency and the secretary.

Because their roles are defined in federal law, any change to the role of NAEP or the governing board would almost certainly require congressional action, said Ms. Orr, NAGB’s director. She said the governing board has so far decided not to issue a position paper on the standards and assessment project because “there’s so much that’s unknown” about where it will lead.

NAGB has had general discussions, though, with the common-core organizers, including an appearance by NGA and CCSSO officials at the board’s quarterly meeting in August to talk about the project.