Includes updates and/or revisions.

State lawmakers want Washington policymakers to back off when it comes to public schools.

Five years after the National Conference of State Legislatures assailed the federal No Child Left Behind Act as a major encroachment on the states’ authority over K-12 education, members of the Denver-based group say that new policies unveiled by the Obama administration are shaping up to be just as prescriptive and intrusive.

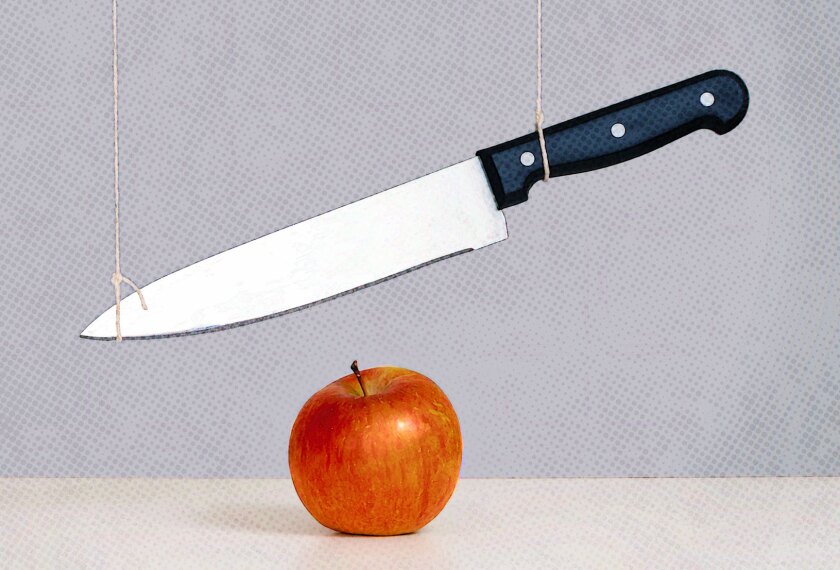

The requirements of the No Child Left Behind law on states—such as expanding standardized testing and meting out rewards and penalties for schools based on student performance—have simply been replaced by other, mostly unproven approaches in the programs put forth so far by President Barack Obama and U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, the lawmakers argue in a new, 35-page report released here Monday.

States, they point out, have scrambled to rewrite laws—acting, for instance, to allow more charter schools—in order to be considered eligible for a share of $4 billion in federal Race to the Top grants, which are part of up to $100 billion slated for public schools under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Though participation in the Race to the Top competition is voluntary, recession-battered states are, in effect, being “coerced” by the lure of money to adopt policies that have not necessarily been shown to raise student achievement, the lawmakers contend.

“If you look at the applications, states have had to change their laws drastically without knowing whether any funding is even coming down to them,” said Robert H. Plymale, a Democratic state senator from West Virginia and a co-chairman of the NCSL task force that wrote the report.

Education department officials under President Obama said they are taking a different approach than that of No Child Left Behind.

“NCLB was loose on the goals, and tight on the means,” said Justin Hamilton, a spokesman for the Education Department. “Both the President and Secretary Duncan believe that we need to turn that equation on its head when reauthorizing ESEA: tight on the goals but loose on the means.”

‘Soup-Kitchen Line’

The task force, made up of 15 members of both political parties, met six times between April 2008 and July 2009 to hear from a variety of education experts. Several of the task force members were also involved in writing an NCSL report released five years ago, which laid out a menu of changes the organization wanted made to the No Child Left Behind Act, which President George W. Bush signed into law in 2002.

Stephen M. Saland, a Republican state senator from New York who also served as a co-chairman, said that if it weren’t for the recession and state treasuries that consequently are “cash starved,” it’s unlikely that all but 10 states would have applied for the first round of Race to the Top money.

“For them, it’s like standing in a soup-kitchen line desperate for sustenance,” said Mr. Saland, whose state was among the 40 that applied for the competitive grants by the Jan. 19 deadline.

And although the Obama administration’s school improvement priorities differ from those outlined in No Child Left Behind, the approach is really the same, the state lawmakers argue. The main areas being emphasized now are tying teacher performance to student data, adopting common standards and assessments, using data to drive instruction, and turning around the lowest-performing schools.

“This is still the federal government picking what they see as winning strategies and telling states, ‘You should do this, do this, and do this,’ ” said Mr. Saland. “It’s still process- and compliance-driven.”

The report argues that the federal government should leave the bulk of K-12 policymaking to the states and to local school districts, but it does call for the U.S. Department of Education to ramp up funding for targeted populations of students—the very disadvantaged and those with disabilities.

The report emphasizes the need for federal education officials to invest in more nonpartisan research that would help guide states and districts when making critical policy decisions.

The federal government is spending only slightly more than 7 cents out of every public dollar invested in K-12 education (which does not take into account the one-time funds provided to schools through the economic stimulus package), according to the NCSL. According to 2006-2007 data from the National Center for Education Statistics, the federal contribution was slightly higher at 8.5 percent. Given that, its stamp on policy should be in balance, Mr. Saland said.

“That’s a disproportionate influence by a player that has the least financial stake in the outcome,” he said.