Includes updates and/or revisions.

In Chicago, the graduation rate for African-American boys is about 40 percent, and only about half of all students are accepted to some form of college. The chances of young black men going to college—particularly young men from the poorest neighborhoods—are not good.

But the Urban Prep charter school, located in the city’s tough Englewood neighborhood, has produced a very different statistic. In March, the school, which is made up of young African-American men, announced that all 107 students in its first graduating class have been accepted to four-year colleges. Just 4 percent of those seniors were reading at grade level as freshmen.

It’s a remarkable achievement for any urban high school, but especially one with a population some people are inclined to write off. It has educators examining what aspects of the school are responsible—and how replicable they are.

Some elements are easy to quantify: an extended school day that means students have an additional 72,000 minutes in school each year, a double period of English, and required extracurriculars and public service.

But many more elements seem embedded into a culture based on four R’s, as the school’s founder and chief executive officer, Tim King, describes it: ritual, respect, responsibility, and relationships.

“I say we give [the students] shields and swords,” Mr. King said. “The swords are hopefully this great education. They know how to read and write and add. ... Equally important, and perhaps more important, are these shields: resiliency, self-confidence, self-awareness. ... Hopefully, we have instilled these things, really woven them throughout the curriculum.”

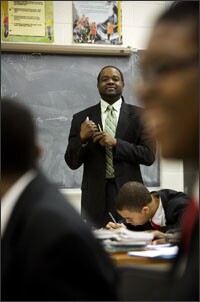

Even small things help, said Mr. King: For instance, the students are addressed formally, using their last name, and they wear coats and ties. (The young men swap their red ties for red-and-gold-striped ones when they’re accepted to college.)

Faculty Commitment

The school of about 450 students is in a neighborhood where violence is pervasive, and many students have to cross gang territory every day. It’s thus crucial for the school to offer an oasis of relative calm.

“For us, it’s not just about teaching new vocabulary words. We really do have to understand what is going on with this student outside school,” Mr. King said.

That means faculty members develop close relationships with students and are available by phone on evenings and weekends. Often, they provide help on issues that seem to have nothing to do with school: homelessness, family tensions, or money problems.

When his mother died this year, Cameron Barnes came to school the next day. “It was like family to me,” said the senior, who plans to attend the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Since his mother’s death, Mr. Barnes has been largely responsible for his household and is the only one who can drive. But he hasn’t lost his focus on college. “I don’t want to be on the street,” he said.

Mr. Barnes was inspired by an older cousin who graduated from college. But for many students at Urban Prep, the teachers and administrators are the first positive male role models they’ve had—and the first college graduates they’ve seen. The faculty and administration are weighted heavily black and male.

The No. 1 criterion in hiring is that teachers believe in the mission, said Mr. King, who noted that some of the most successful teachers have not been black men. But having those role models is important, he added. “None of us are particularly shy about sharing with students our life stories,” he said.

The most notable aspect of Urban Prep’s culture is its focus on college, an emphasis that infuses every aspect of the school—from an achievement-oriented creed that students recite daily to the framed acceptance letters that decorate the walls.

“Every single adult in the building—from the director of finance that handles payroll to the CEO to all the teachers—has a very clear understanding that our mission is to get students to college,” said Kenneth Hutchinson, the school’s director of college counseling. “We start in the freshman year,” added Mr. Hutchinson, who grew up in Englewood. “It’s not about helping them fill out applications; it’s about building strong applicants.”

Senior Milan Birdwell said he always knew he wanted to go to college, but he had no idea how he would get there. When he transferred to Urban Prep as a sophomore, he had a grade point average of 1.6. Since then, he has raised it to 3.04 and posted a respectable score of 21 (out of a possible 36) on the ACT college-entrance exam.

“It’s like someone opened a door, and behind that door is a future,” he said.

Mr. Birdwell had been accepted to five colleges and was waiting to hear from the University of Rochester—his top choice.

The success that Urban Prep has seen so far can be replicated, Mr. King believes. Pedro Noguera, a professor at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, concurs. “What this school shows is that under the right conditions, black males can thrive. They can be very successful,” said Mr. Noguera, who has been researching single-sex black schools. The key to its success isn’t that it’s all-male, he added. It’s “the attention they pay to teaching.”

Adding Campuses

Urban Prep is already expanding. Last year, it opened a campus in East Garfield Park—an African-American neighborhood on Chicago’s West Side. This coming fall, it will open a third campus in the South Shore neighborhood.

Still, certain aspects could be tough to replicate on a large scale. Like most charter schools, Urban Prep raises a sizable amount of its budget, about 20 percent, privately. It operates outside union rules and requires an enormous time commitment from its teachers.

Teaching there is incredibly rewarding, said Eric Smith, the head of the English department, but isn’t for everyone. “There is an emotional cost,” he said. “We’re now surrogate [family] to almost 500 young men. It’s hard finding a balance.”

Despite the school’s success, some challenges remain. While test scores have improved considerably—Urban Prep ranked third out of Chicago’s 98 high schools for growth, according to one model—Mr. King would like them to improve more. The average ACT score is about 17—higher than the district average for African-American boys, but lower than he’d like.

Most important, Mr. King said: College graduation, not admission, is the goal. The school is doing what it can to prepare students for the leap they’ll make when they move to a college campus. For one thing, most students participate in at least one summer college program. Also, counselors will be assigned to all graduates to help them over the next few years.

“It will be very hard for them, which is why we want to have this support piece in place so students don’t give up,” said Mr. King.

The 100 percent acceptance “is a big deal,” he added. “But we don’t consider it a completion of our mission. We consider it a milestone. ... We’re supposed to make sure that they finish college.”