As the number of online Advanced Placement courses rises, more students are accessing those college-level classes than ever before. But teachers, students, and the governing body that authorizes such courses have had to adapt over time to determine how materials should be presented online and whether that method measures up to face-to-face instruction.

High schools that were once limited in the number of AP courses they could offer—whether from a lack of money, isolated locations, or student numbers too low to justify them—now have a plethora of online providers to choose from and free material to access. At the same time, course creators are learning new lessons about how to organize such information, and online-course requirements from the New York City-based College Board, which sponsors the AP program, are also evolving.

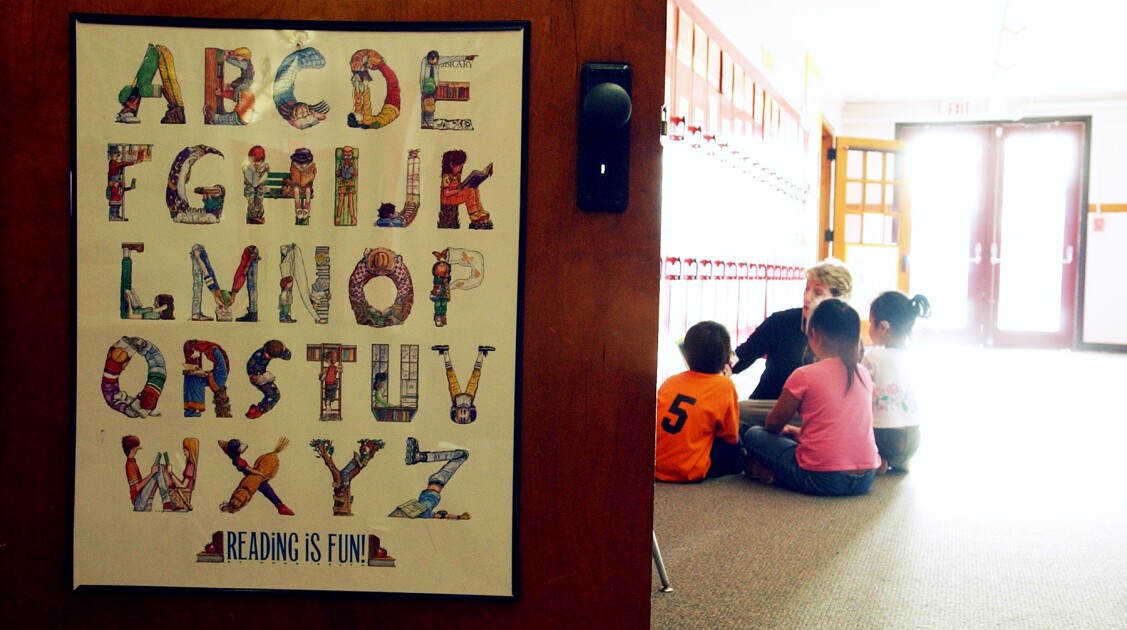

Though many teachers and AP experts insist the best way to dig into an advanced course is in a small classroom setting with face-to-face interactions, even traditionalists acknowledge that the online offerings are an important opportunity for students who previously did not have access to such classes.

“I don’t know if online courses could ever truly replace the face-to-face interaction,” said Steven A. Goldberg, the president of the National Council for the Social Studies and a teacher at New Rochelle High School in New Rochelle, N.Y. He teaches traditional AP courses and mentors students taking an online AP course.

“On the other hand,” he said, “if you are in a remote area or an area where the courses would not otherwise be available, it’s certainly a very viable alternative.”

Changing Requirements

The College Board, which audits all AP courses and authorizes them with its stamp of approval, does not track how many students are taking those offerings online. However, nearly 18 percent of the 17,000 high schools that offer AP courses offer at least one of them as an online option. But those courses, like traditional AP courses, may soon need updating, as the College Board is in the process of changing some requirements.

Some AP courses “have been criticized for being a mile wide and an inch deep,” said Marcia Wilbur, the executive director of curriculum and content development for the College Board. “We’ve ended up with some of our curriculum having way too much content to teach, and it doesn’t allow teachers to go as in-depth as they should.”

As a consequence, course requirements are being retooled to include more-robust content, but with a focus on the development of 21st-century skills, Ms. Wilbur said, starting with some science, history, and language courses. That means less memorization and more emphasis on how to access information, evaluate it, and apply it properly to the topic at hand. The College Board does not evaluate online courses differently from the comparable face-to-face versions; it focuses on evaluating the content of courses and not the way the content is delivered.

In the library of online education, Advanced Placement courses were some of the first to be offered electronically, in part because of attention called to the inequity allowing students in affluent areas to access those courses while those in low-income or rural areas often could not. Organizations such as Kentucky Virtual Schools, a state-affiliated institution based in Frankfort, were actually started with the intent of providing equal access to AP courses, said Kiley Whitaker, a resource-management analyst with the Kentucky Department of Education.

Kentucky Virtual Schools was created more than a decade ago and now offers 23 AP classes, with a full roster of other courses, Mr. Whitaker said.

In the beginning, the school offered only AP courses created by other vendors. Over time, Kentucky Virtual Schools built its own courses, all taught by Kentucky-certified teachers. As the courses have evolved, Mr. Whitaker said, so has their approach. To start, the courses were mostly text-based and often required that a student purchase a companion textbook. Later, courses incorporated multimedia, videos, and other attention-keeping strategies.

“The earlier courses had a lot of static text and were not very inviting,” Mr. Whitaker said.

Students at Kentucky Virtual Schools must pay a quarter of the cost for their courses, and the school or district pays for the rest: $165 for a half-credit course and $330 for a full-credit one. But in what might be the biggest change when it comes to online AP course offerings, much of what is contained in those courses is available for free. The Monterey Institute for Technology and Education, based in Marina, Calif., offers the content of many AP courses at no cost through its National Repository of Online Courses, or NROC. The project began five years ago, in part as a response to a lawsuit on behalf of California students who didn’t have access to AP courses in their schools, said Gary Lopez, the executive director.

Advanced Placement content became the backbone of NROC’s offerings, and it is available for free to students and teachers, though NROC does not provide the online teachers for the courses. The content is not endorsed as official AP coursework by the College Board, but the board does recommend NROC’s materials, Mr. Lopez said.

Integrating Science Labs

The biggest hurdle in the growth of online AP courses has been in the sciences. The lab requirements are often a challenge for online providers, and subjects like biology, physics, and chemistry have seen some of the biggest changes in their online makeup.

Apex Learning, one of the first providers of online AP courses, grappled with the College Board’s emphasis on hands-on lab activities early on, said Cheryl Vedoe, the chief executive officer of the Seattle-based for-profit provider of virtual courses. At first, the company offered more simulated and virtual science labs, but now it has worked toward a mix of live and virtual experiences, she said.

Such a mix can work well, said David Roe, a senior director for AP professional development for the College Board. While Ms. Vedoe said Apex has been successful with that model in most of its science courses, it’s been more challenging for AP chemistry. “We made the decision that it’s too dangerous,” she said. “With AP biology and physics, we’ve reworked our lab activities so they’re hands-on. They require a lab-materials kit, but … there’s no element of danger.”

Because of the element of danger related to mixing potentially hazardous chemicals, Ms. Vedoe said, Apex has restricted chemistry experiments to the virtual kind and has settled for a conditional endorsement from the College Board for the course. The endorsement means the course contains the appropriate AP content, but without the hands-on experiences.

But some teachers believe that without that practical lab work in science courses, students won’t get the same depth of learning.

“The students have to see and smell and be in an environment so they can experience what’s really going on,” said Elham Yasrebi, an AP chemistry teacher at John Adams High School in New York City. “I don’t really believe in online labs for chemistry.”

But Ms. Yasrebi said she also feels lucky that her students have an AP chemistry course—it’s the first one the school has had in more than five years.

Meanwhile, even in a school like New Rochelle High, which offers six different AP courses in the social studies department alone, Mr. Goldberg still finds value in e-courses. His department offers AP psychology online to the small number of students who want to take it.

“This is a good alternative,” he said, “for schools that don’t have the number or the skilled staff to offer the classes.”