Susan Rhodes’ full-time job is helping rural students figure out where they want to go to college and how to make that happen. One of the challenges she faces has nothing to do with her students at Perry County High School, in Linden, Tenn. It’s their parents.

“Parents are never ready, especially if they did not go to college or have that experience,” said Ms. Rhodes, a college-access counselor. “They’re not ever ready for their child to move away. … There is that risk of losing your baby because there aren’t a lot of jobs here.”

The lack of parental and community support is one of the reasons educators say rural students have been among the least likely to go to college. Rural areas have a 27 percent college-enrollment rate for 18- to 24-year-olds, according to a 2007 report from the National Center for Education Statistics, its most recent, compared with the national average of 34 percent and that of cities and suburban areas of 37 percent.

And with the number of students in rural schools growing—the rural share of the nation’s students rose from 22 percent to 24 percent between 2004 and 2009—their success is increasingly important to that of the entire country.

Research shows that low-income students and would-be first-generation college-goers are less likely to attend college, and rural scholars say financial resources and class status are important factors in influencing rural parents’ cultural outlook toward higher education. Also critical, they say, is the role of adult mentors. Rural students who pursue higher education often have families and teachers supporting their college pursuits, researchers say.

Many rural educators believe the dearth of such adult support is among the primary reasons students fail to take the next step into higher education, and some, such as Ms. Rhodes, are working to change that.

Brain Drain

Rural communities have watched for years as their best and brightest leave for college, never to return. Many students move away for jobs and other opportunities their hometowns don’t have. One study estimated only 16 percent of rural residents who remained in their communities were college graduates, compared with 43 percent who left.

“In essence, what you’re doing is taking your child and shipping them out,” said Joe Barker, the executive director of the Southwest Tennessee Development District, a nonprofit association of local governments based in Jackson, Tenn.

Mr. Barker grew up in rural Tennessee. Neither of his parents had a postsecondary education, but they made a middle-class living. That was the case for most of his friends’ families, so encouragement to continue with their education after high school just wasn’t there, said Mr. Barker, who attended college but did not finish.

Now, Mr. Barker works to recruit companies to the same rural area, but businesses want an educated workforce. He sought out and received a $1.5 million grant from the Tennessee Higher Education Commission to change the educational culture of the region by helping students explore, apply to, and enroll in college. It’s modeled on the program for which Ms. Rhodes works. Nineteen schools in 12 counties are benefitting from mentors who help students with the application process, whether it’s completing financial-aid forms or talking with their parents.

“What we have always focused on in economic development is things like roads, sewer, and buildings, which are all needed, but we were missing the most important component, and that is the workforce,” he said. “If we don’t have this in place, we’re never going to be economically successful.”

Mr. Barker, like many other rural advocates, says the long- term solution is changing the community’s culture. Research shows rural parents have lower educational attainment expectations for their children than those who live in cities and suburbs.

“We know this is going to take time,” Mr. Barker said.

A Student’s Perspective

Michael Hankins is one of the students Ms. Rhodes worked with at Perry County High. He’s a sophomore at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, and he’s majoring in chemistry with plans to go to medical school. He has a 4.0 grade point average.

Mr. Hankins is the first in his family to go to college, and his factory-worker parents didn’t know anything about the application process. He would have been alone in the process had it not been for Ms. Rhodes.

Ms. Rhodes was a critical sounding board and information source. When he was trying to figure out where to go to college, she suggested his current school. He didn’t know much about it, and it wasn’t one of his top choices. That changed after Ms. Rhodes arranged for him to make a campus visit.

And when he faced the daunting task of filling out financial-aid applications, she walked him through the maze of forms. She continued to help him after he graduated from high school.

“I was glad she was there,” Mr. Hankins said. “I know she made a difference for me. There’s a lot of people who got a lot of good information from her.”

Mr. Hankins said his parents supported his decision to go wherever he wanted for college, but many of his friends’ parents pressured them to stay close to home. Many of his peers ended up at schools where they didn’t really want to be and since have quit, he said.

“There’s a lot of pressure on us to stay close by,” he said. “I don’t know why.”

Mentoring and encouragement, while valuable, are only part of the equation when it comes to increasing high school students’ readiness for and access to higher education, in the view of William Tierney, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Rossier School of Education.

Research does show that mentoring programs positively affect college enrollment, but it also would suggest it’s more important for students to have the academic skills to be accepted into and stay in college, Mr. Tierney said.

“I can tell you what is essential—ensuring kids are reading and writing at grade level,” Mr. Tierney said.

A 2009 report he co-authored, “Helping Students Navigate the Path to College: What High Schools Can Do,” included among its research-based recommendations that surrounding students with adults and peers who support their college-going aspirations can help students build a college-going identity and encourage them to pursue their goals.

Validating Success

The Niswonger Foundation, based in Greeneville, Tenn., caught the attention of the federal government for its college-readiness and-access efforts, winning one of the highly sought-after Investing in Innovation grants, receiving a five-year, $21 million award.

The foundation organized 29 mostly rural Northeast Tennessee high schools into a consortium that’s using six tactics to make students more college-ready. Some of those relate to students’ academic preparation, such as expanding dual enrollment and online and Advanced Placement offerings.

Other efforts include providing additional college- and career-counseling resources to students, such as specialists to work with existing guidance counselors.

The schools also are working with parents, many of whom didn’t go to college and fear what will happen to their children who do so, said Ms. Linda Irwin, the director of school partnerships for the Niswonger Foundation. The project is, for example, taking parents on college visits with students, hosting financial-aid-application workshops, and developing online tutorials.

Community Culture

Wade McLean understands how a community’s culture can affect students’ desire to achieve a postsecondary education. He worked as a superintendent in the rural Whiteriver, Ariz., school district, which enrolled about 2,000 low-income students on a Native American reservation.

The issue for his students wasn’t financial, said Mr. McLean, an education consultant and board member of WestEd, a nonprofit research and development agency based in San Francisco. They receive ample federal support for college tuition, books, and housing, he said. And parents took great pride in their children’s college acceptances and scholarships, he said.

But families want their children back on the White Mountain Apache Reservation, he said. Some students who made it to college refuse to visit the reservation because the push for them to stay would be too great to bear, he said.

“They put a real guilt trip on their children,” he said of the families.

Mr. McLean compared his students’ experiences with those of inner-city students who are ridiculed for doing well, saying the issue may be one of poverty rather than geography.

“Where there’s high unemployment and high poverty, they look down upon success,” he said of such communities. “I think it boils down to a cultural expectation that students shouldn’t be successful in higher education.”

‘Right Fit’

School-level counselors are on the front line when it comes to navigating tricky cultural issues and supporting and nurturing rural students’ college aspirations.

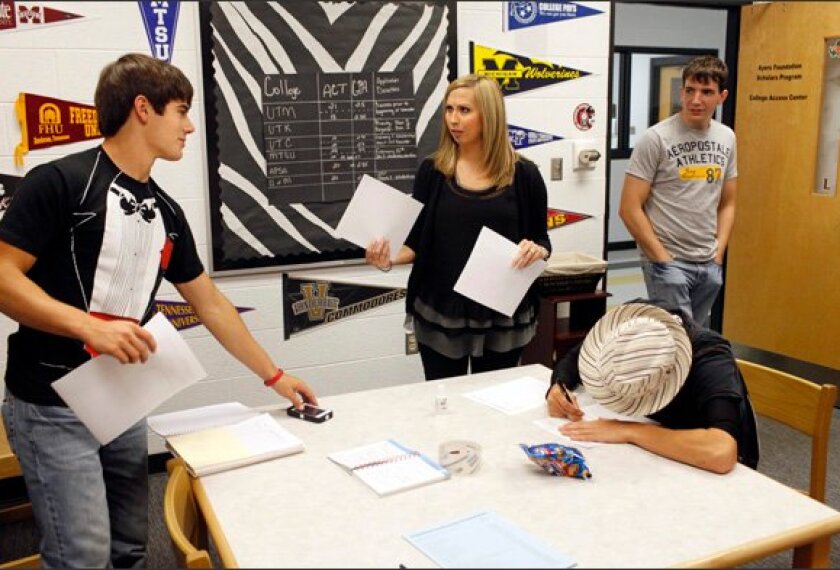

At Perry County High, in Tennessee, Ms. Rhodes has been a college-access counselor since 2009. Eighty-six percent of the school’s 68 seniors from the class of 2010 enrolled in a postsecondary institution, about double the national average.

Although Ms. Rhodes works for the school, she’s paid by The Ayers Foundation, based in Parsons, Tenn., which has been providing college-access counselors and last-dollar scholarships to high schools since 1999 to encourage more students to go to college.

Guidance counselors, particularly in rural schools such as hers, are taxed with so many responsibilities, from standardized testing to scheduling, that they have relatively little time to concentrate on getting students into college, Ms. Rhodes said.

Some students want to stay in the community and do the jobs their family members have done, such as weld on a pipeline. Ms. Rhodes said she supports those students, but she also lets them know a welding certification from a nearby technical education program will enable them to earn more money.

“I want them to make the decision, but I also want them to know all the options,” she said.

Parents don’t necessarily keep students from going to college, Ms. Rhodes said, but they can prevent students from choosing the school that’s best for them. Sometimes that’s because students’ top choices are far from home, and parents don’t want to see them move, she said.

She tries to take parents along on a student’s campus visits, and many times they end up supporting their child’s choice, she said. She also tries to have individual meetings with high school seniors’ parents as well as host activities for specific grades.

“It’s really hard for a parent to understand finding a good fit for a student if they didn’t go to college themselves,” Ms. Rhodes said. “We’re trying to find the right fit as opposed to the closest school.”