As students navigate changing sexual and social norms in middle and high school, many of them confuse the line between joking and sexual harassment, according to a new report.

Based on the first nationally representative survey in a decade of students in grades 7-12, the study, which was set for release this week by the American Association of University Women, found that 48 percent of nearly 2,000 students surveyed had experienced verbal, physical, or online sexual harassment at school during the 2010-11 school year.

The students’ reports reveal constantly shifting school environments—mostly unseen by the adults on campus—in which students use everything from gossip and teasing to groping or more severe physical attacks to enforce gender stereotypes, bully, and retaliate. Nearly a third of victims become harassers themselves.

Researchers found that while students generally don’t see themselves as sexual harassers, 14 percent of girls and 18 percent of boys reported that they had harassed another student, either in person, online, or both. The report says that 44 percent of those who sexually harassed another student considered it “no big deal,” and that another 39 percent said they were trying to be funny.

To explore the impact of sexual harassment on students in grades 7-12, researchers surveyed 804 students who had experienced harassment either in person, online, or both. Their findings suggest that being harassed both online and in person compounds the effect on students.

SOURCE: American Association of University Women

“If people who are harassing think they are joking and the victim is trying to respond by laughing or trying to turn it into a joke, it confuses things,” said Holly Kearl, a program manager at the Washington-based AAUW and a co-author of the report. “Prevention just has to be key, and that is what is not being done so much. We don’t want all these kids being suspended and expelled for something they don’t recognize as being wrong.”

The distinctions between teasing, bullying, and sexual harassment are becoming more critical as the U.S. Department of Education’s office for civil rights focuses more on school harassment data. The main federal law prohibiting gender-based discrimination, commonly known as Title IX, requires districts to protect students from gender-based behavior that would create a hostile academic environment, and the civil rights office has been requiring more-detailed reporting from districts on episodes of sexual harassment. The first nationwide OCR data on that topic are expected in the coming months.

“As the bullying crescendo rose, schools have been replacing their sexual-harassment policies with bullying policies, and they’re not the same thing,” said Nan D. Stein, an education professor and sexual-harassment researcher at Wellesley College in Massachusetts who was not involved with the AAUW study.

New Avenues for Abuse

Ms. Stein said most of the teachers she works with are “well versed” in sexual-harassment issues, but tend “to think about it in a physical way—groping, grabbing, that kind of stuff.”

The addition of social media complicates the situation, because those networking tools can easily extend harassment beyond campus. The study found that more than one in three girls and nearly one in four boys had been harassed through texting or social media; through incidents such as being sent sexual pictures, jokes, or comments; or having such things posted about the student.

The researchers found that students who were harassed both online and in person reacted more strongly than those who faced abuse in only one area. For example, students harassed both in person and online were more than twice as likely to feel nauseated, have trouble sleeping or studying, not want to go to school, or switch schools or activities as were students who were harassed only in person or online.

“There’s an amplification when it’s both,” said Catherine A. Hill, the AAUW’s director of research and a co-author of the report. “Online is instantaneous, invasive, 24-7. It’s particularly well suited to creating this illusion that everyone thinks this.”

Girls were more likely than boys to experience most forms of harassment, but both were equally likely to be harassed based on gender stereotypes; for example, a boy wearing bright colors or a girl in sports might be called “gay” or “fag,” while a girl who physically developed earlier than her peers may be called a “slut.” While boys were more likely than girls to report being able to shrug off harassment, abuse was likely to interfere with academics for both sexes. More than one in 10 students said they had stayed home from school or gotten in trouble at school because they were harassed, and nearly one in three found the harassment interfered with their ability to study.

“It’s kind of hard to educate kids who are experiencing this harassment and violence and expect them to show the same performance they would regularly,” said Bruce G. Taylor, who studies sexual harassment as a principal research scientist for NORC, a research organization formerly known as the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago; he was not involved with the AAUW study. “These are the kinds of problems that could really fester into long-term problems for these kids.”

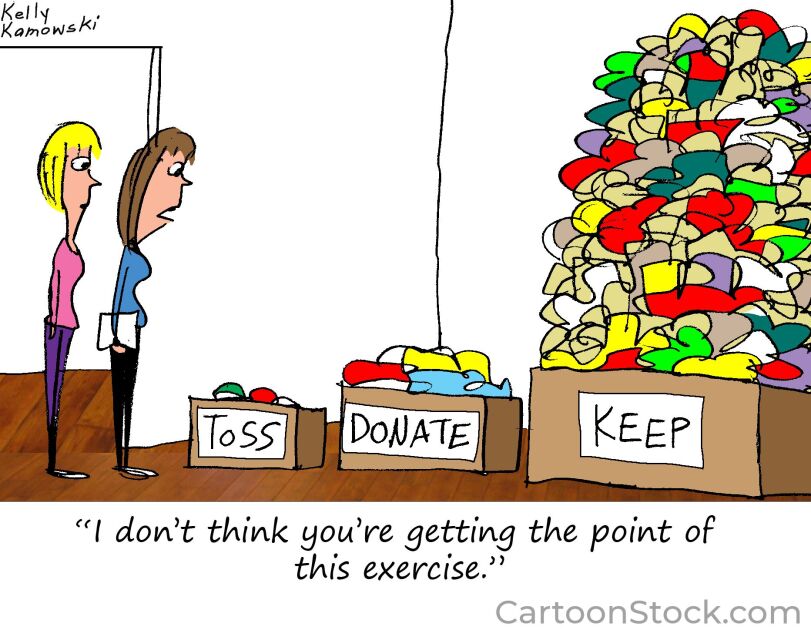

What makes matters worse, the researchers noted, is that prevention programs often do not address the complexities of the problem. Many school-based anti-harassment programs focus on teaching students to develop healthy romantic relationships, but the AAUW study suggests that approach may miss the point: Only 3 percent of students who had sexually harassed another student said they acted because they wanted a relationship with the victim.

Respecting Boundaries

“The prevailing notion when people talk about teen-dating violence is to talk about healthy relationships, which I think is a … paternalistic approach. Who decides what is healthy?” Ms. Stein said. “It’s how do you understand someone else’s personal boundaries and how do you get people to respect your boundaries.”

Ms. Stein and Mr. Taylor are developing and evaluating a holistic approach being used in some New York City middle schools since 2008. As part of the program, called Shifting Boundaries, schools post information on sexual harassment and gather focus groups of students, both within classes and campuswide, to talk about the school’s sexual environment and legal and school rules related to harassment.

In one activity, students map out “hot spots” in the school where they feel most unsafe.

“Inevitably, it’s the least-supervised areas that are marked as least safe,” such as restrooms used by older students or rear corridors, Ms. Stein said.” In response, she said, school administrators were able to change travel patterns or change hall-monitor locations.

A 2010 study funded by the U.S. Department of Justice of 30 New York City middle schools found schools that implemented the program saw 26 percent to 34 percent fewer instances of sexual harassment after six months, 32 percent to 47 percent fewer instances of sexual violence, and 50 percent less physical and sexual dating violence than at the start of the program.