Like almost 14 million other Americans, Monica Reyes is looking for work.

“Macy’s, Walmart, Kmart, Sears, Friday’s, Outback,” said Reyes, ticking off her list of recent unsuccessful job applications.

A sluggish economy has made finding work difficult for people from all walks of life. Nationally, the unemployment rate is still above 8 percent. Four people compete for every job.

Few of them will have a tougher time finding work than Reyes.

For starters, last year, she was shot. “Monica Reyes” is not her real name. The incident has yet to make its way through the courts, and Reyes continues to fear for her safety. As a result, the Notebook/NewsWorks has agreed to use a pseudonym in this story.

In addition, Reyes, 20, hails from Kensington, where jobs are scarce and trouble is commonplace. Sixty years ago, the area was a vibrant manufacturing hub. Now, it’s a graveyard of abandoned factories and home to one of the largest illegal drug markets in the region.

“Growing up in that neighborhood, I went through war,” said Reyes matter-of-factly.

But perhaps the biggest obstacle to Reyes’ finding work is her failure to finish high school.

In Kensington and Eastern North Philadelphia, the unemployment rate for young adult dropouts is close to 50 percent.

While staggering, that number only begins to tell the story. Roughly 1,500 of the 3,000 or so dropouts aged 20-24 in this part of the city are not even trying to find work and are therefore not counted in unemployment statistics.

That means that only one in four young adults without a high school diploma in Kensington/Eastern North Philly has a job. Citywide, it’s about one in three.

Listen to Monica Reyes’s story in this radio feature from reporter Benjamin Herold.

“There’s a period of eight or ten years where a lot of decisions really come together and set your life path,” said Paul Harrington, director of the Center for Labor Markets and Policy (CLMP) at Drexel University, which conducted an analysis of labor market outcomes for youth for the Notebook/NewsWorks.

Harrington called the situation “just disastrous.”

Mayor Nutter has made reducing the city’s high school dropout rate a priority. In 2011, for the first time in memory, the city’s four-year high school graduation rate inched above 60 percent.

But citywide, the youth labor market is still in the tank, especially for dropouts.

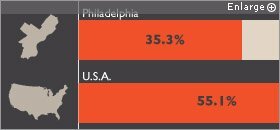

Only 55 percent of all 20-24-year-olds in Philadelphia have a job. For those who have left school without a diploma, that number drops to 35 percent.

Harrington compared the situation to a bus with just a few empty seats but a long line of people waiting to get on.

“Those who get on first, and who get the best seats, have the highest level of educational attainment,” he said. “And then way at the back of the line are the young high school dropouts who have no work experience.”

The Heart of the Problem

In many respects, Kensington/Eastern North Philly is the epicenter of the city’s dropout and unemployment crisis.

Bounded by Germantown Avenue on the west, Wingohocking Street on the north, and Girard Avenue on the south, the area is known to the U.S. Census Bureau by the arcane designation of PUMA 04105.

It’s home to some of the most devastated sections of Philadelphia. In few areas of the country have the decline of American manufacturing, the war on drugs, and the latest recession converged so disastrously for young people.

Take Monica Reyes.

Since dropping out of Kensington High School for the Creative and Performing Arts at 17, her troubles have mounted.

What are 20-24 year-old dropouts doing?

Percentage of 20-24 year-olds who are employed

SOURCE: Todd Vachon for NewsWorks

On a whim, she quit her last job, selling sneakers, and she’s been unable to find work since. She terminated an unplanned pregnancy, a decision that still haunts her. Her father died. After getting shot—"wrong place, wrong time,” she explained—she spent a few weeks in the hospital. Last summer, she was arrested for marijuana possession, her latest minor run-in with the law.

“It just seemed like the problems built up,” said Reyes.

The slow, seemingly inexorable path to her current predicament began in 8th grade, when her mother moved her family from a small apartment in East Kensington to the heart of the so-called “Badlands.”

Drugs—and the accompanying crime and violence—were everywhere, she said.

“A person like me could walk down the street on a regular day, four in the afternoon, and have a guy pull over trying to beep-beep the horn at you because they think you’re a prostitute.”

As the indignities and traumas piled up, Reyes lashed out. After faring well in the District’s high school selection process, Reyes started 9th grade at Roxborough High in Northwest Philadelphia. But she quickly got kicked out for fighting. She spent two years at Shallcross, an alternative disciplinary school, before her final, brief stint at Kensington CAPA.

Reyes attributed many of her problems to the neighborhood’s destructive environment.

“If you wanted to live somewhere, it would not be that place,” she said quietly.

It used to be different, said Philippe Bourgois, an anthropologist at the University of Pennsylvania who is studying Kensington. “When this was a thriving working-class industrial neighborhood, it was wonderful,” he said.

The key was an abundance of manufacturing jobs with low entry requirements, decent pay, and union protections.

Now those opportunities for high school dropouts have all but disappeared. In their place is a smattering of unstable service jobs in retail, security, health care, and mom-and-pop businesses.

The steadiest, most accessible work is selling drugs.

“People are arriving every day with handfuls of dollars, looking for heroin and cocaine,” said Bourgois.

For many young people, the promise of fast money, combined with the difficulty finding legitimate work, begets a vicious cycle.

“You have a whole set of people who are selling very part-time just … to fix their car or pay their rent,” said Bourgois. “But you can’t sell drugs in a city like Philadelphia for more than six months without ending up in prison.”

Once a young dropout has a criminal record, of course, the chances of finding work plummet further.

Holding Out Hope

Despite the long odds, Reyes hasn’t given up.

Her recent brush with the law turned into an opportunity. As part of an alternative sentencing program, she was directed to an organization where she performs community service while pursuing her GED.

On a January morning, she sat in a basement room with seven other young women, studying fractions.

“175 and 100, what goes into both of those?” instructor John McLaughlin asked.

“Five?” answered Reyes tentatively.

“Is there a bigger number?” pushed McLaughlin.

“Ten?”

Schoolwork, particularly math, is slow in coming back.

But if Reyes can complete the 13-week course and get her GED, her job search could get a big boost.

According to Drexel’s CLMP, young adults in Kensington/Eastern North Philly are twice as likely to have a job if they also have a high school diploma or equivalent.

“A high school diploma opens the door to opportunity,” said Neeta Fogg, a Drexel researcher who helped conduct the CLMP analysis.

That possibility offers Reyes a ray of hope. She wants to emulate her cousin, who was recently accepted into a training program to become a home health aide.

“She’s about to get a job making $11 an hour,” said Reyes. “I’m like, ‘Damn, that sounds good.’”

Before she can even apply for training, however, she needs her GED.

“I wish I finished school when I was supposed to,” said Reyes.

“I definitely want to work.”