A kindergarten teacher in a San Diego public school last fall referred six of her students—all English-language learners—for evaluation for special education. All of them, as it turned out, needed eyeglasses; one needed a hearing aid. None needed to be placed in special education.

A few years ago, such simple explanations for the students’ academic difficulties might not have been picked up so early. But last year, the 132,000-student San Diego district—with a history of lopsided referrals of English-learners to special education—created a step-by-step process to make sure every explanation and intervention for a child’s lagging academic performance had been examined before assigning a placement in special education.

“Special education had become the default intervention,” said Sonia Picos, a program manager in the district’s special education department. “Special education was seen as the place with the answers, without taking into consideration what the long-term implications were going to be for the students.”

Accurately identifying ELL students who also need special education services has long been a problem for educators. Historically, English-learners were overrepresented in special education, but litigation and civil rights complaints have, in more recent years, led to an equally troubling problem with identifying too few ELLs with legitimate special education needs, or not providing services to them in a timely manner.

National research done within the last decade, including a 2003 study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Education, found that overidentification occurred more commonly in districts with small numbers of ELLs (fewer than 99 such students), and underidentification was more common in districts with larger English-language learner populations.

More recent data, however, seem to suggest that underidentification might be the larger issue on a national level: In 2009-10, English-learners comprised 9.7 percent of students enrolled in public schools, but made up 8.3 percent of public school students being served under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. And by 2030, English-learners will comprise an estimated 40 percent of the American student population.

The heart of the problem, educators and researchers say, is discerning whether students are simply struggling with acquiring English or truly have disabilities that are impeding their progress.

It’s a challenge that the Education Department is trying to help districts tackle, starting off by commissioning an exploratory study of a half-dozen districts that will document, in detail, the procedures and techniques that educators are using to identify English-learners for special education.

Among students with disabilities, “there seems to be evidence in some areas of overrepresentation of English-learners, and in some areas of underrepresentation of English-learners,” said Liz Eisner, an education research analyst with the department who is one of the staff members overseeing the new study. “I’ve heard educators say that it is often hard to validly identify students and disentangle the disability from the language problems.”

One of the difficulties is that so many of the assessment and evaluation tools for determining whether students have disabilities are intended for students who speak a single language, usually English, and who are proficient in it.

Study’s Scope

The Education Department’s project will include interviews with district staff members and the collection of documents—without compromising students’ privacy, Ms. Eisner said. The goal is to understand how different students’ cases progress from referral to placement, or not being placed, in special education. Results are expected in late 2013.

Since the reauthorization of the idea in 2004, districts have had the option of using response to intervention, or RTI, which allows teachers to intervene when students are floundering regardless of whether the students are identified as having disabilities.

The districts selected by the department will include those that have had a long history of serving English-learners and those experiencing a surge in their ELL population, and a combination of districts that are using RTI and those that don’t. RTI involves using an escalating set of techniques to address students’ deficiencies when they are struggling.

Using RTI can prevent incorrect referrals to special education, but can have drawbacks, too, such as delaying a student’s evaluation for a disability by a school psychologist.

San Diego’s Struggle

Faced with a class action five years ago over the poor quality of its special education services, the San Diego school district hired Thomas Hehir, a Harvard Graduate School of Education professor and a former special education chief in the federal Education Department, to take a hard look at how students were faring.

Among the 15 states with the largest shares of English-language learners in their special education programs, the percentages of such students vary widely.

California: 29.39 percent

New Mexico: 23.31

Nevada: 19.32

Alaska: 14.91

Texas: 14.51

Colorado: 11.90

Oregon: 10.68

Utah: 10.31

Washington: 9.79

New York: 9.27

Virginia: 8.27

Hawaii: 7.88

Connecticut: 7.15

Florida: 6.98

Delaware: 6.63

50 states, D.C., and Puerto Rico: 8.30

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education

Among Mr. Hehir’s most jarring findings: Latino English-language learners were 70 percent more likely than their Latino peers who were not English-learners to be referred to special education.

In a follow-up study two years later, Jaime E. Hernandez, a longtime bilingual special educator in Los Angeles who helps monitor that district’s compliance with a special education consent decree, examined records of San Diego English-learners placed in special education and found several red flags. English-learners were being identified for special education, on average, earlier than their non-ELL peers; they were more likely to be placed in restrictive settings; and there had been limited use of assessments in their primary language—typically Spanish—to evaluate them for special education. Mr. Hernandez also found little evidence that educators had considered extrinsic factors such as health, family conditions, or previous learning environments that could explain a child’s academic struggles.

“What was obvious from that work was that we needed to be much more comprehensive in how we evaluated our English-learners, and we definitely needed much more collaboration across departments,” said Sandra Martinez, the executive director of special education in San Diego.

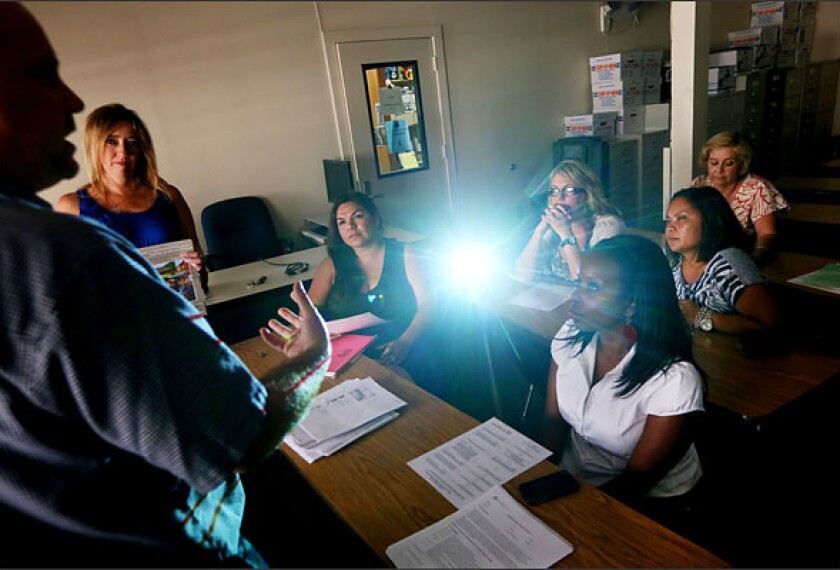

So the district set out to create a comprehensive evaluation process for English-language learners that would “slow everyone down” and “look at all the features of a child’s life” before getting to the point of referring him or her to special education, Ms. Martinez said. The goal was valid referrals and accuracy of special education decisions for ELLs, so educators and specialists from across the district—bilingual teachers, special educators, psychologists—developed a set of procedures for district staff members to follow when students are flagged as possibly needing services.

The new system, put in place last fall, starts as a “pre-referral” process that requires educators to try a series of appropriate general education interventions tailored to each student’s situation before making an actual referral to special education.

In San Diego, closely examining “extrinsic factors” in students’ lives is key to that pre-referral process, said Ms. Picos, including figuring out if lack of parental involvement, attendance issues, nutrition, or frequent moves, to name a few, might explain a student’s academic troubles. Educators also must determine whether students have received good instruction and support in English-language development.

“This whole pre-referral process is RTI,” Ms. Picos said. “If we take a close look at these extrinsic factors, we can individualize what each student needs, and in many cases, find the appropriate intervention.”

Only after educators have exhausted the general education support options for ELLs and still don’t see improvement do they refer students to special education for evaluation.

Talking the Talk

At that point, valid and reliable assessment of students is critical and is often where districts struggle most. Many either can’t or don’t evaluate students in their primary languages.

“When most of the tools that are used to assess learning disabilities are in English and were normed on monolingual English-speaking kids who are part of the dominant culture, you can’t rely on that to tell you if a child with a different primary language has a learning disability or if they just don’t know the language,” said Kathy Escamilla, an education professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She has done research on the impact of assessment practices on Spanish-speaking students.

Assessing ELLs for special education was a hot topic at a conference of the Waltham, Mass.-based Urban Special Education Leadership Collaborative earlier this year, said Will Gordillo, the director of exceptional-student education in the 177,000-student Palm Beach County district in Florida.

The multicultural team that works on evaluating ELLs for disabilities in his district includes bilingual psychologists and speech-language therapists. While most of the district’s English-learners speak Spanish or Haitian Creole, the district hires interpreters and consultants when necessary to work with students and families who speak other languages.

And, as in San Diego, Palm Beach County has detailed guidelines for evaluating children. Though students ultimately may not be diagnosed with disabilities, the process may lead to providing additional language supports, Mr. Gordillo said.

An even thornier issue, Ms. Escamilla said, is how to deal with U.S.-born English-language learners who don’t have strong literacy skills in their primary language. Most ELLs are born in the United States, she said, and many don’t receive formal instruction in their first language, so assessing them for special education in that language “isn’t reliable.”

For school psychologists, questions remain about what practices will best increase the accuracy of the identification of disabilities in ELL students, said Mary Beth Klotz, the director of idea projects and technical assistance for the National Association of School Psychologists, in Bethesda, Md.

“I would start by paying extra attention to all the idea safeguards and requirements for any special education evaluation, since they ring extra true for ELLs,” she said. Using multiple sources of data is important because many typical evaluation tools don’t have the same reliability and validity for ELLs.

She said schools should expect evaluations for ELL students to take longer and compare their progress with that of similar students.

“If the only comparison is with an ELL student’s monolingual peers,” Ms. Klotz said, “the conclusions may not be meaningful, valid, or fair.”