Requiring students to take part in community service to graduate from high school can actually reduce their later volunteering, new research suggests.

Maryland’s statewide requirement that all students complete 75 hours of service learning by graduation led to significant boosts in 8th grade volunteering—generally in school-organized activities—but it actually decreased volunteering among older students, leading to a potential loss in long-term volunteering, according to a study previewed online by the Economics of Education Review in June.

“If this is for school, how do we know [students] are considering this as community service, rather than just homework for school?” said the study’s author, Sara E. Helms, an assistant professor of economics at Samford University in Birmingham, Ala. “One of the interpretations that is more convincing is, maybe we are substituting this [requirement] for being self-motivated. Does it dilute the signal value of volunteering?”

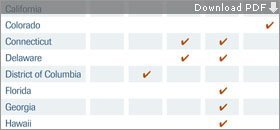

Service learning—in which students engage in projects and activities to improve their communities or address social problems—has become more popular in the past decade. In 2011, 19 states allowed districts to award credit toward graduation for volunteering or service learning, and seven states allowed districts to require service for graduation, according to data collected by the Education Commission of the States. In 2001, only seven states allowed high school credit for service.

Districts on Board

While Maryland remains the only state to require universal service learning as a condition of graduation, the District of Columbia school system began requiring 100 hours of community service in 2007, and several other large districts, including Atlanta, Chicago, and Philadelphia, also require community service for graduation.

Service learning has been growing in popularity. More states and districts are adopting policies to incorporate service learning into their requirements for high school graduation.

SOURCES: Education Commission of the States; Education Week

If Ms. Helms’ interpretation is correct, the new findings undermine some of what proponents have argued makes service learning so popular. Prior studies have found students who volunteer more frequently tend to be higher-achieving, more engaged in their communities, and less prone to risky behaviors as adolescents. Moreover, service learning in particular has been found to improve students’ engagement in school and reduce their risk of dropping out, and Maryland’s policy was touted as a way to help students “develop as citizens,” Ms. Helms said.

“I’m pro-service learning,” she said in an interview. “However, I think it matters how we implement it. What you hear over and over in the literature is, don’t require service learning; give incentives. We get very nervous about requiring people to do something because it’s good.”

Early Boosts

The study used student data from Monitoring the Future: A Continuing Study of the Lifestyles and Values of Youth, a nationally representative annual survey of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders, to compare Maryland students’ volunteering trends with those of other American students during the same time period.

From 1991 through 2011, nearly three in four American high school seniors reported doing community service at least a few times a year, with 31 percent volunteering at least monthly and 12 percent volunteering weekly. Among 8th graders, 65 percent volunteered at least a few times a year, 26 percent volunteered monthly, and 10 percent volunteered weekly.

Ms. Helms graduated from high school in Maryland two years before the service requirement was enacted for the class of 1997. She recalled family conversations about how her younger brothers would meet the criteria.

“It was pretty controversial when it was put into place,” she said. “It was a mixed bag. You hear stories where students got involved with something because they had to complete service hours, and it changed their life and they went into social justice to try to stop poverty—and then you hear the stories of, ‘Oh, my dad’s friend let me do something to help out,’ ” Ms. Helms said.

In each year, the students were asked as part of the Monitoring the Future survey to report how often they had volunteered: never, a few times a year, at least monthly, at least weekly, or nearly daily.

In the first years after the Maryland policy took effect in 1993, the proportion of the state’s 8th graders who reported weekly volunteering increased nearly 6 percentage points compared with the time before the requirement. The increase dropped to 3.2 percentage points above pre-requirement levels by 1998, however, and to only 2 percentage points above pre-requirement levels by 2010.

The proportion of 8th graders volunteering at least monthly initially rose by 7.4 percentage points in the early years, compared with the pre-requirement level.

But there was no significant difference between the volunteering of Maryland 8th grade students and those in other states, suggesting that some of the increase could have come from a general trend toward more service learning.

It was a different story among older students. Before the requirement, Maryland seniors were 7.8 percentage points more likely than students nationally to be engaged in service activities—driven primarily by rising service activities among boys and following a national trend of more volunteering during that time. After the service requirement, Maryland seniors were 9.2 percentage points to 17.4 percentage points less likely to volunteer from 1997 to 2011.

That contrast is particularly notable because national volunteering among 12th graders rose during the same time.

R. Scott Pfeifer, the executive director of the Maryland Association of Secondary School Principals and a former principal of Centennial High School in Howard County, Md., cautioned that the findings may underrepresent subtler volunteer activities among older students because students may be better able to recall and report official school-related volunteer activities, such as those they would pursue during middle school.

“There’s a ton of volunteering that goes on,” he said, but “kids are social animals. They may not think of their activity in National Honor Society of bringing food to the old-age home as volunteering.”

‘Part of the Culture’

Service learning, Mr. Pfeifer said, is “part of the culture now; it’s pretty routine. In terms of the actual graduation requirement, looking for systematic ways that groups of kids and classes can fulfill that requirement just works for everybody. It doesn’t get to that individual volunteerism, but it works.”

Both Ms. Helms and Mr. Pfeifer agreed that schools’ service-learning programs require planning and time for students to reflect on their experiences in order to be meaningful.

Mr. Pfeifer argued that the service-learning requirement is not intended to be primarily about building civic character.

“Some people might have thought this would build up an individual sense of volunteerism,” he said. “I don’t think it ever really achieved that focus, because there’s a bureaucratic nightmare that could come from that. So instead we’ve used it tied to the curriculum.”

And as a tool for engaging students in different subjects, from history to environmental science, Mr. Pfeifer argues that the state’s service-learning requirement has been a success.

“Without it, there’d be something lacking in every one of our schools that’s there now, a focus,” he said. “There’d be something missing if [the service requirement] wasn’t there.”