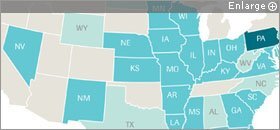

Only one state—Pennsylvania—collects and then cross-references data from five major early-childhood-education programs and makes the information available to authorized users through its own K-12 data system, a new survey finds. But many other states are working to put similar plans in place or are aiming to connect early-childhood education, health, or social-service records to K-12 school databases.

Moreover, states should make coordinating all education, health, and social service program data a top priority, according to the report issued by the Bethesda, Md.-based Early Childhood Data Collaborative, an umbrella group advocating for the better use of information for individual children to improve the quality of and access to early-childhood education. Doing so, the group asserts, would make it easier to track student progress, pinpoint problems, identify underserved groups, and inform instruction.

Without such linkages, “you’re not getting a snapshot of how programs work and are progressing over time,” said Carlise King, the executive director of the data collaborative, which last week issued its “2013 State of States’ Early Childhood Data Systems.” In most cases, children’s information is stored in multiple, uncoordinated systems managed by different state and federal agencies, the survey found.

Privacy Concerns

But that’s exactly where it should stay, some privacy advocates say.

“There’s a huge push for this to happen based on what we think is very uncertain evidence that this data collection will create better schools,” said Leonie Haimson, the executive director of Class Size Matters, a New York City-based nonprofit that advocates for student privacy, among other issues. “I can see there are reasons why you might want to share information, … but keeping it in one place under one organization, whether private or governmental, is very worrisome.”

States vary widely when it comes to linking child-level data from five key early-childhood programs and their own K-12 data systems. Those programs range from state-funded pre-K to federally funded programs such as Head Start.

SOURCE: Early Childhood Data Collaborative

The data collaborative, formed in 2009, is a partnership made up of the Council of Chief State School Officers, the National Conference of State Legislatures, the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, the Data Quality Campaign, Child Trends, a non-profit research group, and the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at the University of California, Berkeley.

In July 2013, the collaborative surveyed all states and the District of Columbia on how well they linked data between their K-12 systems and what the group identified as five major state or federally funded early-childhood programs, including state pre-K, Head Start, special education, and federally funded child care.

Among the findings:

• There are 26 states that link early-childhood-education data across two or more publicly funded early-care and -education programs;

• Thirty-six states collect state-level child-development data from early-childhood-education programs, and 29 states capture kindergarten-entry-assessment data.

• States’ coordinated early-childhood-education data systems are more likely to link information among programs for children participating in state pre-K and preschool special education than for children in Head Start or subsidized child-care programs.

• Thirty-two states already have governance systems to guide the development and use of such linked information.

The data are intended to be of practical use to education policymakers, said Paige Kowalski, the director of state policy and advocacy for the Washington-based Data Quality Campaign, which aims to harness data and use them to make informed decisions.

“The goal is not to collect a lot of data about kids, then … provide it for everyone,” Ms. Kowalski said. “The goal is to answer the questions: ‘Are our kids ready to start kindergarten? What kind of environment is best?’ And for legislators, ‘Which kinds of programs should we scale up and scale back?’ ”

States’ Responsibility

But more data means more chances for manipulation or misuse, Ms. Haimson said. Aggregate data might be a useful way to nail down trends, but much of the information kept will be looked at by teachers, for example, and will be of a very personal nature, she added.

“There are reasons to keep medical records separate from education records separate from criminal-justice and child-service records,” she said. “Parents have a fear of what states will do with data and who the data will be shared with.”

Ms. Kowalski, however, said that such personal information could prove necessary to families who, for example, are building an evidence-based case for the need for special education services.

And states ultimately will have the responsibility to protect such information, Ms. King said, which is why so many are developing criteria for data development and management.

Douglas A. Levin, the executive director of the Washington-based State Educational Technology Directors Association, said that federal and state privacy laws create a framework for protection already.

“I am not aware of any rules or issues that would affect the handling of data about minors by public institutions that change because they are very young,” Mr. Levin said.