After tensions here boiled over into rioting this week, Baltimore educators sought to turn the events into a chance to engage students in reflection and learning about some of the issues that touch their lives most deeply.

Protestors have marched in the city demanding answers about what led to the April 19 death of Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old black man who died after suffering a spinal cord injury while in police custody. On May 1, Baltimore’s top prosecutor announced charges against six officers in the death, including second-degree murder, involuntary manslaughter, and assault.

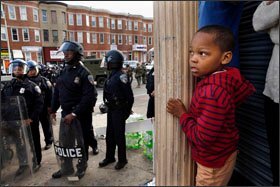

Earlier in the week, peaceful protests gave way to a night in which some rioters burned cars, looted buildings, and pelted police officers with rocks. Officials canceled school for April 28.

When he announced the reopening of school after the one-day closing, Gregory E. Thornton, the Baltimore district’s chief executive officer, promised classroom activities and events to help students process what happened.

“Despite that it came after days of rising tension, yesterday’s violence felt like a shockwave across the city,” Mr. Thornton wrote in a letter to parents. “But I am writing to tell you that it will not overwhelm us.”

Baltimore’s turmoil recalled the weeks of unrest in Ferguson, Mo., last year after a black teenager was shot and killed by a white police officer, and it came after months of national discussions about race and the use of force by police. And it stirred questions about the role of schools in helping students process distressing events in their cities.

The Baltimore district posted a discussion guide on its website with links to classroom materials about Ferguson and Eric Garner, a black man from New York City man who died after a confrontation with police.

Underlying Issues

On the day schools in Baltimore were closed, community groups, coffee shops, churches, and libraries opened to feed students who may rely on subsidized meals normally provided in school. Of the district’s 85,000 students, 84 percent qualify for free or reduced-price meals.

Students who gathered around the city that day said that when they returned to class, they wanted to discuss not only Mr. Gray’s death, but also the economic, racial, and social issues that have contributed to mounting frustrations here. Before the rioting, some teachers had been hesitant to talk about the situation, students said.

“It’s like discussing religion in class almost,” said sophomore Katie Arevalo, 16, who’s been involved in peaceful demonstrations since Mr. Gray’s death. “It’s difficult because you don’t know the different perspectives or how people are feeling.”

Students said they worried how people in other parts of the country would perceive their city after viewing images of the destruction. And they were concerned about how their own city viewed them after some youths were involved in an initial clash with police that preceded the rioting on April 27.

On that day, the day of Mr. Gray’s funeral, some students circulated on social media a call for a high school “purge,” or a period of lawlessness, at a local mall. That afternoon, young people, including some students from a neighboring high school, pelted police who had responded to the scene with rocks, bottles, and debris.

In his letter to parents, Mr. Thornton praised “the thousands and thousands of students who made good decisions.”

“A small minority of our students did not make responsible decisions, and I am deeply angered that the inexcusable actions of those few now threaten to color perceptions about the many,” he wrote, adding that those students “will be held accountable.”

President Barack Obama condemned the rioting, and called on the nation to address education and poverty issues, in addition to seeking changes in law enforcement.

“If we are serious about solving this problem, then we’re going to not only have to help the police, we’re going to think about what can we do, the rest of us, to make sure that we’re providing early education to these kids to make sure that we’re reforming our criminal-justice system so it’s not just a pipeline from schools to prisons,” the president told reporters.

As schools reopened in Baltimore on April 29, teachers used social media to share students’ art, essays, and activities reflecting on what had happened in their city. Much of that reflection had started the day before at events like one held at the city’s Teach For America headquarters, where dozens of students met with volunteers, including teachers, to talk about issues surrounding the response to Mr. Gray’s death.

“Kids have a lot to say. They also have a lot of questions,” Julie Oxenhandler, a 6th grade math teacher, said at the discussion. She said she was working to learn more about the Baltimore demonstrations so she could answer students’ questions.

“Freddie Gray could have been my students’ brother or cousin,” she said.