It’s the middle of spring testing season, and a bevy of accountants, technology geeks, lawyers, unemployed corporate executives—and oh, yes, teachers—are scoring the PARCC exam.

The room has the generic feel of any high-volume office operation: Seated in front of laptop computers at long beige tables, the scorers could be processing insurance claims. Instead, they’re pivotal players in the biggest and most controversial student-assessment project in history: the grading of new, federally funded common-core assessments in English/language arts and mathematics.

The PARCC and Smarter Balanced assessments aren’t the only tests that require hand-scoring, but the sheer scope of the undertaking dwarfs all others. Twelve million students are taking either the PARCC or the Smarter Balanced assessments in 29 states and the District of Columbia this school year. Large portions of the exams are machine-scored, but a key feature that sets them apart from the multiple-choice tests that states typically use—their constructed-response questions and multi-step, complex performance tasks—require real people to evaluate students’ answers.

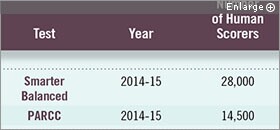

And that means that 42,000 people will be scoring 109 million student responses to questions on the two exams, which were designed by two groups of states—the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium and the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers, or PARCC—to gauge mastery of the common core. That unprecedented scoring project is testing the capacity of the assessment industry and fueling debate about what constitutes a good way of measuring student learning.

The scoring process is typically shrouded in secrecy, but Pearson, which is training scorers for PARCC states, as well as administering and scoring the test, permitted a rare visit to one of its 13 regional scoring centers, in a nondescript brick office building outside Columbus.

Inside is Launica Jones, who on a recent day had been scoring the answers to 3rd grade math questions. The 23-year-old taught elementary school for a while, but now she’s going to law school at night, and scoring the PARCC exam by day for extra cash. On a break, she walks a reporter through the process. The problem asks students to analyze the multiplication calculations of two fictional students, decide which is correct, and explain why.

“See?” she says, pointing at the computer screen displaying the question. “This one gets only one point [out of four]. He got the part about which child was right, but he didn’t say why.”

As millions of nervous students sit down at computers to take the exams this spring, they can’t tell that their longer answers are being zapped out to real human beings, who score them at home or in corporate scoring centers. But here those scorers are on a recent afternoon, Ms. Jones and about 50 other men and women, sitting in long rows, evaluating 3rd graders’ answers to math questions. They don’t score the entire PARCC exam here; individual questions are divvied up and distributed to scoring centers nationwide.

Learning the Ropes

On this day, the scorers—called “raters” in industry-speak—are at various stages in their training. Some, like Ms. Jones, have passed a qualifying test and are scoring real students’ answers. Others are still in training.

In one corner of the room, a group of 10 aspiring scorers are discussing how to grade the same math problem Ms. Jones has been rating. They’ve studied for two to three days to win approval to score this one item. They’ve examined “anchor sets” of pregraded and annotated student answers. They’ve studied 10 or more additional practice sets of student answers to learn to distinguish a complete answer from a partial one.

All of those materials are compiled in thick notebooks, along with grading guidelines, for the would-be raters to use as they consider dozens of student answers to this one math problem. Now they’re peppering their supervisor with questions.

If a student has the correct answer, but forgets to add the dollar sign, does he get credit? What if a student shows a sound strategy, but an incorrect calculation? The supervisor walks through each student response with her group, explaining the correct way to score each one. When these men and women complete their training, they’ll take a qualifying exam designed to demonstrate that their scoring consistently falls within the ranges that Pearson and educators from PARCC have agreed upon.

Smarter Balanced has a more decentralized way of training scorers, since each state using that test chooses its own vendor to administer and score the test, and train raters. While Pearson requires PARCC scorers to hold bachelor’s degrees, for instance, Smarter Balanced lets each state set its own minimum requirements, said Shelbi K. Cole, the deputy director of content for Smarter Balanced.

California offers an example: Through its contractor, the Educational Testing Service, the state is hiring only scorers who have bachelor’s degrees, though they can be “in any field,” according to an ETS flyer. Teaching experience is “strongly preferred,” but not required. Certified teachers, however, must be paid $20 per hour to score, while non-teachers earn $13 per hour. As of late April, only 10 percent of the scorers hired in California were teachers, according to the state department of education.

Regardless of their incoming qualifications, however, all Smarter Balanced raters will have to reach a common target: after training, they must be able to show that they can consistently score answers within approved ranges of accuracy, Ms. Cole said.

Clearing that hurdle doesn’t ensure job security, though. Their work is monitored as they score, and if their scores don’t agree with those of pregraded, model answers often enough—70 percent to 90 percent of the time, depending on the complexity of the question—they can be dismissed. “Once a scorer, not always a scorer,” said Luci Willits, the deputy director of Smarter Balanced.

The PARCC and Smarter Balanced tests, combined, require more people to score answers than any of the top large-scale national assessments.

*Note: Includes state results as well as national results. In some years, state results are not reported.

Sources: Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium, Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers, Pearson, National Center for Education Statistics, Educational Testing Service

Focus on Reliability

That monitoring process is similar to the one in use at Pearson. During raters’ training, and later, when they’re officially scoring, Pearson scoring supervisors intermittently “back read” selected papers to make sure their scores fall within acceptable ranges, said Robert Sanders, Pearson’s director of performance scoring. They also slip pregraded models of student work into the student responses from time to time, to see if scorers grade them correctly, he said.

In the Pearson scoring center, each student answer generally gets scored by a single rater. Ten percent of the responses, however, are read by two raters to verify consistency in scoring. Some responses might be reviewed by Pearson staff members if scorers flag them for a variety of reasons, such as illegible handwriting or responses written in languages other than English.

As they review raters’ work, Pearson staffers meet and talk with those who are scoring too high or too low in an attempt to remedy that “drift,” Mr. Sanders said. A few must be dismissed, and some leave training before becoming raters. In the training for 3rd grade math scoring, for instance, 85 percent of those who were hired as scorers made it through the qualifying test and went to work as raters, Mr. Sanders said.

Pearson reports that among the scorers hired as of April 30, 72 percent had one or more years of teaching experience, but only half are still teaching. Any teaching experience—not just that obtained in mainstream public or private K-12 classrooms—is acceptable, Mr. Sanders said.

Advertising for Scorers

Recruited through postings on sites such as CraigsList, Monster.com and Facebook, Pearson raters are paid $12 per hour initially. Logging more hours can bump their pay up to $14 per hour. There’s performance pay, too: a track record of quality scoring can earn bonuses of $15 to $30 per day. Raters on the day shift stay for eight hours; those who work at night typically work four to six hours. Scorers who train and work from home—three-quarters of those scoring the PARCC tests for Pearson—commit to score 20 hours per week.

The time on task matters because Pearson staffers monitor raters’ productivity. Acceptable scoring speeds are based on Pearson’s past experience scoring tests. Those reviewing 3rd grade math, for instance, are expected to score 50 to 80 answers per hour, while raters for 3rd and 4th grade English/language arts responses are expected to complete 20 to 40 per hour, and those scoring high school English/language arts responses are expected to complete 18 to 19 per hour, Pearson officials said.

In scoring student responses, scorers rely on materials created by teams of Pearson staff members and educators from PARCC states, who met in several rounds earlier this year to evaluate thousands of student responses to questions from the field test. They chose answers that demonstrated a wide range of levels of mastery. Those answers, with detailed explanations added, became models of what appropriate answers for each scoring level should look like.

Question of Capacity

As the massive test-grading proceeds, assessment experts said they’re acutely aware that the scale of the undertaking imposes new demands on the industry.

“Doing a hand-scoring project this massive in scope certainly does present some challenges to our field,” said Chris Domaleski, who used to oversee large-scale testing as an associate superintendent for the state of Georgia, and is now a senior associate at the Center for Assessment, a Dover, N.H.-based group that helps states develop and validate their assessment systems.

Joseph Martineau, a senior associate at the center, said his worry isn’t focused on the subjectivity of 42,000 human scorers. Established practice in the field ensures careful training and monitoring, making hand-scoring “much more of a science than people think it is,” he said. But he questioned the assessment industry’s capacity to supply a key component: the supervisors who train and oversee those scorers.

"[Hand-scoring the Smarter Balanced and PARCC tests] requires a major increase in scoring capacity of the vendors,” said Mr. Martineau, who used to oversee testing as a deputy state superintendent in Michigan. “You have to have table leaders, team leaders, who are really good. Those may be few and far between.”

If the vendors who are training raters adhere to best practices, as outlined in the psychometric industry’s Bible—the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing—Mr. Domaleski said, he is optimistic that the scores will be reliable and valid. Some of those practices include requiring appropriate qualifications of scorers, creating a rigorous process to qualify them as scorers, and monitoring whether they’re scoring within expected ranges.

“At the same time, though, I don’t want to minimize the risk of how difficult it’s going to be, given the extraordinary scope of these operations,” he added.