In the newly-released movie American Gangster, Denzel Washington plays Frank Lucas, initially ignored by certain Sicilian businessmen as just another entrepreneur competing for the market held by his recently deceased employer and the Harlem distributor of their product. Lucas copies the Italians’ family-based business model, bypasses their upstream channels by forging a direct connection to manufacturers, and develops independent relationships with government regulators, enabling him to offer a product twice as effective at half the price. When they finally recognize the competitive threat, the New York families conclude that convincing Lucas to join their collective is a better business strategy than trying to eliminate him, and Lucas agrees.

(Note: “The Letter From” was previously the “Letter From the Editor” in School Improvement Industry Week, renamed to join the edbizbuzz lineup.)

Lucas became part of the system by beating the dominant players at their own game, not by changing the rules of the game. And his story is really the exception that proves the effectiveness of those rules. In his business, for every Frank Lucas, there are literally thousands of also-rans, has-beens and never-weres.

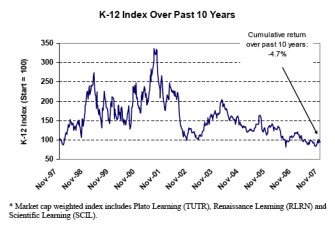

Which brings us to a chart in the October 2d issue of Education Signals, the newsletter from Trace Urdan and his colleagues at the education investment banking firm Signal Hill, pictured here.

Their “take-away?” Had you invested in 1997 in a market weighted cap index consisting of Plato, Renaissance and Scientific Learning - three school improvement providers challenging the multinational publishers for tax dollars spent on instructional products and services - your cumulative return would be a five percent loss.

How is this possible over a decade of ever-increasing government interest in high standards and accountability, investment to provide schools with supporting tools and techniques, and rhetoric about the need for programs that work? To a greater or lesser extent that many are ready to debate, each company offers programs based on research and evaluation, with better evidence of efficacy than the fare provided by dominant publishers for decades. Is this a problem explained by “business risk” – management that’s not up to the task, poor marketing decisions, costs out of control, etc, etc? Or is it about something else?

I think it’s about political risk (listen here, download here). If you invested in these companies thinking that they could take on and beat the major publishers just because their products were better – if you thought they were k-12’s Frank Lucas, I’m afraid you were one of those fools and his money soon parted. The new entrants’ annual gross revenues would be lost in the dominant players marketing budgets. The history of American business is littered with failed companies with better products. I wrote about one last week.

But there was “smart money” in these firms, based on legislative changes – especially, but not exclusively at the federal level with No Child Left Behind’s Scientifically Based Research provisions – that suggested the dominant players’ competitive advantage could be neutralized. Indeed note the spike in index value around the time of NCLB’s passage. If efficacy became the criteria schools were required to apply to their procurement decisions, marketing budgets would become irrelevant. Established “brand equity” would give way to “what works” and the new firms would be great investments. But as the Reading First scandal investigations have shown, the Department of Education failed to give the provisions any teeth. And at the state level – despite changes to instructional materials adoption laws like California’s placing nonprint media on par with textbooks, regulations continue to place the new firms’ products at a disadvantage.

My bottom line is simple. Plato, Renaissance and Scientific Learning aren’t Frank Lucas and won’t be. They can’t beat the publishers at their own game. At best, they can be bought out on the cheap. If companies like these are to meet investors initial expectations, the changes already made to the rules in state and federal legislation need to be completed in regulation and enforcement. If poor management does play an important role in their firms’ struggles, it would have to be the fact that none have engaged sufficiently in the political struggle required to advance and protect the emerging rules that served as the basis of their value proposition to investors. For example, none of their trade groups are seriously committed to high quality program evaluation, and they have not tried to start one that is. No one is going to do it, if these companies don’t themselves. With a multi-year reprieve on the gutting of NCLB, there is still time, and investors in these companies should demand that their managers get moving.

You can listen to the podcast version of this Letter here.

P.S. Close observers might understand that in k-12 education, Frank Lucas’s approach could be called the Riverdeep strategy.

P.P.S. I’ve been told by at least one education reporter that I ought to post my response to their inquiry about the insights on k-12 companies provided by firms like Signal Hill, Baird, and Eduventures in publication and interviews. It falls within an old rule of thumb for the analysis of Washington politics - Miles’ Law: “where you stand (on the issues) depends on where you sit (around the table).” Here goes, barely edited so as to avoid the need to include the full e-mail exchange:

The critical point w/all is that they make their money either by assisting in the sale or purchase of k-12 firms’ equity (Baird, Signal Hill) or doing very large consulting work for them (Eduventures). So it’s not in their interest to be seen as casting doubt on their clients or potential clients. In this respect their analyses have to be looked at like those of any other interest group. They are very competent, but all have a dog in the fight.

The only other point I’d make here is that in this arena of industry analysis the analysts are not as experienced as in others. There’s a better grasp of the underlying “technology” and overarching politics in say aerospace or banking stocks, than in k-12. And this is why they’ve tended not to inquire deeply into what works and to underestimate political risk - and so have facilitated the development of a school improvement industry sector that isn’t much of a threat to the dominant business paradigm of publishing.

(Download this as a podcast here.)