Includes updates and/or revisions.

Educators and families on the Red Lake Indian Reservation in Minnesota were picking up the pieces last week after a deeply troubled 16-year-old student shot and killed seven other people and himself at a high school March 21.

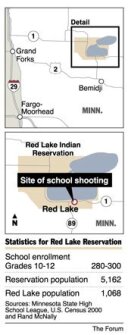

The nation’s deadliest school attack since the 1999 slayings at Colorado’s suburban Columbine High School took place on an isolated reservation that spreads across 564,426 acres of woodland just south of the Canadian border.

Red Lake High School, its windows shattered and walls pocked with bullet holes, likely will not reopen for months, local officials said. Students at the 355-student school were expected to be taught this week in community centers on the reservation. Red Lake’s elementary and middle schools were also scheduled to resume classes.

See the accompanying items:

Internet Postings Linked to Student Highlight Interest in ‘Hate Groups’

Stuart Desjarlait, the superintendent of the Red Lake school district, said at a March 24 press conference at North County Regional Hospital in Bemidji, Minn., that the high school has a crisis-management plan and had conducted drills. It also has a metal detector and security guards. But no one can guarantee 100 percent safety, 100 percent of the time, he added.

“We did everything we could,” the superintendent said. “It goes to show that if something’s going to happen, it’s going to happen. No matter what you do, no matter who you are, no matter what precautions you take, something like this can happen.”

Jeff Weise, brandishing several guns and supplied with multiple rounds of ammunition, burst through the school’s front door after shooting and killing one of the school’s two unarmed security guards. Within 10 minutes, he had shot and killed five students and a teacher, then turned a gun on himself. At least seven other people were injured, two of whom were in critical condition last week in a Bemidji hospital.

Before arriving at the school, Mr. Weise shot and killed his grandfather, Daryl Allen Lussier, 58, and Mr. Lussier’s companion, Michelle Leigh Sigana, 32.

Red Lake is a “closed” reservation, subject to federal but not state laws. The Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians runs its own police force and court system and sets policy on who can live on or visit the reservation.

The staunchly independent community, wary of outsiders, was deluged after the shootings by the news media and a network of grief counselors, psychologists, and victim-witness assistants from the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Stronger Schools

More than 100 law-enforcement officials, from the FBI to the local Red Lake tribal police, were conducting hundreds of interviews in an investigation expected to last for weeks. Authorities said Mr. Weise, who was being taught at home, did not leave a suicide note or other explanation for his attacks.

Paul A. McCabe, a special agent in the FBI’s Minneapolis office, described the school after the rampage as “a very traumatic crime scene.”

Killed at the school were teacher Neva Rogers, 62; security guard Derrick Brun, 28; and students DeWayne Lewis, 15; Alicia Alberta Spike, 14; Chase Albert Lussier, 15; Thurlene Stillday, 15; and Channelle Rosebear, 15.

Those familiar with the Red Lake reservation emphasized that while life on “the Rez,” with its high unemployment and poverty rates, is difficult, it is not without hope.

Bryan Lussier, 42, the director of the tribe’s employment-rights organization, said that schools on the reservation have improved significantly since his childhood. Not only are the buildings and facilities in much better condition, he said, but school staff members and administrators also show far more interest in both the academic and personal needs of students.

“Teachers are a lot [closer] to students now,” said Mr. Lussier, a distant cousin of two of the shooting victims: student Chase Lussier and Mr. Weise’s grandfather Daryl Lussier, who was a tribal police officer.

David Beaulieu, who visited Red Lake several weeks ago, echoed that sentiment. He is the president of the National Indian Education Association, which is based in Alexandria, Va.

“You could just tell the sense of caring [the educators] had for the young people, and in the way they interacted with them,” he said.

And a consultant who has visited Red Lake in recent years said the district had taken an active role in trying promote a safe environment in its schools.

Gregory M. Olson, the founder of Critters and Company, a Champlin, Minn., group that uses animals in teaching lessons designed to curb bullying and violence, said he has made several appearances at the district’s elementary and middle schools in the past three years.

It was sometimes a challenge to keep Red Lake’s students interested during his presentations, Mr. Olson recalled, especially at the middle school. But he saw noticeable improvement in students’ attentiveness over time, and he credited school officials with helping foster that turnaround.

He believed Mr. Weise was too old to have been in the audience during his presentations.

Dean Carlblom, a representative of Education Minnesota, the 70,000-member state teachers’ union, was one of the first to talk to Red Lake educators after the shootings.

“Most of them are still in shock, and the staff from the other [schools] are very numb,” he said March 24. “All of the educators were pretty much washed out by the end of the day yesterday.”

Difficult History

Yvonne C. Novack, the Minnesota Department of Education’s manager of Indian education, said a cross-agency team of school psychologists, mental-health counselors, and others has been made available to Red Lake.

Ms. Novack said her office advised state workers on how to operate within the cultural norms and traditions on the reservation, respecting the tribe’s religious ceremonies, the leadership role of tribal elders and the tribal council, and the tribe’s independence of state government.

Courtesy of The Forum, Fargo-Grand Forks, N.D.

Jeff Weise had an exceptionally difficult personal history. His father committed suicide in a police standoff in 1997, and his mother lives in a nursing home as the result of brain injuries sustained in a car accident, according to press reports. The teenager apparently had a strained relationship with his grandfather, and he was being taught at home due to unspecified medical problems.

He was depressed and taking Prozac, had previously tried to commit suicide, and saw a mental-health professional as recently as Feb. 21, members of his family told the media.

At times, he bore the brunt of classmates’ teasing, news accounts said, and he is believed to have posted entries on an Internet site run by a neo-Nazi group.

But some people familiar with Red Lake say the picture being painted of the young man as a threatening loner who wore all-black clothing is not accurate, according to Mr. Carlblom of Education Minnesota.

“There was a different side of Jeff, a couple of people said,” Mr. Carlblom noted, adding that some people had found Mr. Weise friendly, if not outgoing. “In the Native American culture, they joke with each other. Everyone teases each other. Sure, he got teased, but how much of that was serious?”

One student, Michelle Kingbird, 13, told television reporters that Mr. Weise was her friend and that he was “funny” and “cool.” Ms. Kingbird, whose stepbrother, 15-year-old Ryan Auginash, was wounded in the attack, went on to say that she couldn’t believe Mr. Weise was the type of person “to do what he did,” and that she forgave him.

Still, Mr. Weise’s circumstances underscored some of the problems faced by Native American youths.

American Indian students make up about 1 percent of the U.S. public school population, and more than 90 percent attend traditional public schools. The rest attend schools overseen by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs.

One in four Native Americans was living in poverty in 2000, twice the rate of the rest of the U.S. population, according to a 2004 study by the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development.

One in six Indian youth has attempted suicide, the study found. And Indian children were 60 percent more likely to report having taken part in a fight at school in the most recent year, the Harvard report said.

But Gordon Adams Jr., a member of the Bois Forte Band of the Chippewas in Nett Lake, Minn., cautioned against drawing links between socioeconomic troubles in Indian communities and the actions of a single troubled student at Red Lake High.

“Our family settings are just the same” as in non-Indian communities, Mr. Adams said. “People are kind of throwing this into the stereotype that we all come from broken homes.”

When poverty or dysfunction affects a single Indian student or family, “someone will always step in and make sure that child is brought up,” he said.

The Real Educators?

But while Indian education officials elsewhere reacted with shock to the Red Lake slayings, some said they were not surprised that such violence had touched one of their communities.

Pauline M. Begay, the superintendent of the Apache County, Ariz., school system, which oversees 11 districts in the northern part of the state, said the important factor in preventing violence in schools is encouraging families to take an active role.

“When it comes to parental involvement, there’s just not enough of that,” said Ms. Begay, who is on the board of directors of the National Indian Education Association. Parents, she said, “are most often absent in the education of the student.”

Stephen Sroka, a school security consultant and an adjunct assistant professor at the Center for Adolescent Health at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, said rural youths may be more influenced by television, the Internet, and movies than their metropolitan counterparts, primarily because of their isolation.

“The educators today on sex, drugs, and violence are not teachers,” he said, “but the media.”

Schools need a three-part approach to help prevent crises, he said: prevention education, physical security such as metal detectors and cameras, and access to mental-health care for students.

“We need to move beyond metal detectors,” Mr. Sroka said. “We need to put a human face on school security.”

Scott Staska, the superintendent of the 2,300-student Rocori school district, 15 miles southwest of St. Cloud, Minn., is one educator who knows from experience what those in Red Lake are going through. On Sept. 24, 2003, Jason McLaughlin, a 16-year-old student at Rocori High School, allegedly shot and killed two classmates at the school. He is now awaiting trial.

Mr. Staska spoke to Chris Dunshee, the principal of Red Lake High School, briefly on March 24 and advised him about the variety of mental-health and other services the school should use.

“Take advantage of all the help you can get,” Mr. Staska said he told the Red Lake principal, “because you can’t do it alone.”