This post is by Caitlin LeClair, principal of King Middle School in Portland, Maine.

On a Wednesday afternoon in late October a student focus group gathered in the library of King Middle School. They were eager to find out what their charge would be. When I told them that student input guides next steps for our school-wide goals and professional development, a skeptical seventh grade student asked a pointed question. “Mrs. LeClair, if you want us to be honest with you, will you promise that you will really do something with all of our feedback?” I paused and took a moment to reflect. Our students are why we come to work every day and they are our first priority. They are the “consumers” who understand the teaching and learning experience at King better than anyone. “Yes, I can promise you that your voice matters,” I assured her. My voice was confident, but I also worried that following students’ lead might be a circuitous or, worse, dead end journey. I hoped my worries were unfounded.

King is an EL Education network school located in Portland, Maine. By several measures, King’s population is one of the most diverse schools in the state:

- 52% of its 540 students receive free and reduced price lunch

- 65% are in single-parent households

- 22% were born outside the United States

- 31 languages are represented

- 20% are identified as needing special education services

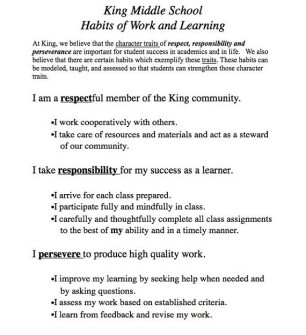

The challenges and assets that come with such diversity inform our mission to prepare students to be leaders in a complex world by giving them the tools to develop the critical thinking and problem solving skills they’ll need in college and beyond. Among these tools are Respect, Responsibility, and Perseverance--habits of character that matter just as much as strong academics. We believe these character traits are more than ineffable qualities granted to some people and not others. Rather, we believe they can be modeled, taught, practiced, and assessed as students learn how to treat equipment and use resources, how to prepare for and participate in class, how to approach assignments, how to produce their best work, how to seek help, how to ask questions and express skepticism, how to accept feedback and make improvements, and how to assess their own work.

Four years ago our staff worked to develop our Habits of Work and Learning (HOWLs) rubrics and structures to teach and assess these habits. But as the seventh grader’s question revealed, students really hadn’t bought into the system adults had created. The questions and comments the student focus group raised would help us transform our school-wide documents and approach to teaching, tracking, and assessing our character habits.

With the guidance of our students over the course of the year, we reflected on what was working and what needed improvement. Here’s what we learned:

Less Is More

Students were overwhelmed with the number of targets that were being assessed and density of the rubrics, which were used inconsistently by students and teachers.

Actions and results: We developed a teacher-led action team to work with the student focus group and collect teacher feedback. Over the course of the year they reduced the number of targets and revised the rubrics. All stakeholders were involved in providing feedback throughout the process. Finally, the last round of feedback on the documents came from students, who gave it a thumbs up!

Clarity and Consistency are Crucial

The focus group revealed that “meeting” HOWLs targets often looked different in different classes. They also wanted to see those targets more explicitly linked to everyday life and situations they face on a daily basis.

Actions and results: The action team facilitated professional development in which all teachers were asked to bring artifacts of best practice in connection to teaching and assessing HOWLs. We also had discussions about the new rubrics and created “What this looks like” descriptors for each target. Additionally, we spent time digging into the new rubrics to discuss how to calibrate for consistency while also allowing for teacher flexibility.

Listen to All Stakeholders

In February a member of the student focus group asked why we weren’t asking all students what their opinion of HOWLs. What a great idea!

Actions and results: With input from students and teachers we developed a school-wide survey for students. All students took the survey and the results were synthesized and posted throughout the school. We also used professional development time for teachers to take a deep dive into the student feedback and determine possible next steps for the school.

At the end of the year it was clear that our work had been a true team effort, with all voices heard and valued. Did everyone get exactly what they wanted? No. However, everyone did feel that they were part of the process and had a voice that was helping to drive us forward. The seventh grader who had begun the year with skepticism acknowledged that I kept my promise and was eager to learn what we would work on the next year. It was an important reminder that school is not something we should “do” to children. It should be done with and for children. Hitting the pause button to involve students in a respectful and authentic dialogue created a greater sense of shared ownership of what we value at King and what teaching and learning can be: a place for students to lead their own character learning--and to affirm the hopeful and striving character of an entire community.

Photo credit: King Middle School