After a nine-month transition, I left my beloved job at Teach For China in April to return to the United States to be closer to my family. I still work part time, continue to stay in touch with students and teachers and, most importantly, still Facebook stalk everyone.

This week, I’m posting a poignantly honest reflection I read online by first-year Teach For China Fellow Taylor Loeb sharing how the CORE project, the program empowering students to be community leaders in rural China, influenced some of his most struggling students. It’s a long read, but worth seeing a young teacher evolve his understanding of education. If you want to support students to have these once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to find their passions and believe in themselves, go here to learn more and donate to CORE.

Zach is 12, a rather young age to decide who is “dumb” and who isn’t. Zach, unfortunately, it has been decided, is “dumb.” He’s never been in love, he’s never put a car into drive, he’s never sat at the adults’ table. But it’s been decided that he’s “dumb.”

Strangely, the kids tabbed as “dumb” are given the least attention, at least in the mountains of China where I live and teach. This is a pretty precarious situation for Zach, who is supposed to have at least 3 years of compulsory education left. He’s placed at the back of the class with other students like him. If he can’t keep his hands to himself or shut his mouth, he’s encouraged to read quietly or put his head down instead of participating. He complies because what 6th grader wouldn’t agree to that deal?

Little does Zach know that every second he spends with his head on his desk is a second of education he will never get back.

There’s no layaway for grammar points. He can’t comprehend how bopping his deskmate today on the head during a lesson about quadrilateral shapes is going to affect whether in 10 years he has a desk job with health benefits or stands on a factory assembly line for 13 hours a day. It’s nearly impossible for him to connect the dots between an assignment on the future tense and the actual future.

And, he shouldn’t. That’s not Zach’s job. That’s my job. Weeding out the “cans” from the “cannots” is the way education is structured perhaps everywhere, but most certainly in China. Once you’ve been marked, you’re either in for an adolescence of an uphill battle or a self-fulfilling cruise toward higher education. Whether Zach’s in Sanzhaung, Sao Paulo, or Sydney, that’s the way it is. But for Zach and his friends, this is how it looks in our town of Sanzhuang, China.

I am a first-year American educator who teachers English as a Foreign Language to 36 sixth graders in rural China. Based on historical statistics, about half of them will go to high school. Of that 18, maybe three to five will go to any college at all, let alone the higher tiered universities that companies choose to hire from. You’ve got to be extraordinary to do that.

Factor in that 100% of students’ parents didn’t go to college. Factor in that almost all of their teachers didn’t either. Factor in that college, even if tuition is totally free, still incurs a staggering opportunity and living cost for students in rural Yunnan.

Take this into consideration and Zach’s unjust predicament begins to make sense. At some point as a teacher, it seems, you’ve got to put your chips on the table. If you’re teaching 40 to 90 students, among who four have a realistic shot at higher education and only half can make it to freshman year of high school, you’ve got to give them that chance. There simply aren’t enough hours in the school day to get Zach up to speed in long division, let alone times tables. He had his chance. He missed it. It’s over. Put your head on your desk and bask in the blissful ignorance of a disappearing education.

Zach’s not going to college. Zach’s not going to high school. But, that does not preclude Zach from receiving a meaningful education on his terms. It’s not the system that’s screwing Zach over; it’s the system’s resources. Too many students, not enough teachers, not enough support, not enough time.

I am not a great teacher, especially in my first year in this exam-intensive system. The reality is that few teachers want to come to my village and I’ll never be as good as a local English teacher who’s been through the process, knows the ins and outs, and can perceive with almost Nostradamus like efficiency, what is and isn’t going to be on the county-wide final exams. What I’ve realized that I and other Teach for China fellows can provide, however, is a new perspective on what’s possible for Zach and others.

I don’t let Zach read or sleep in my class. At the very least, he has to call back vocabulary words like everyone else. He is almost illiterate in Chinese, so in English class I just tell him to do his best, but don’t over scrutinize his work.

The other day I was giving a review lesson about superlatives. Taller! Older! Stronger! Bigger! On a scale of excitement, the lecture was somewhere between a James Lipton monologue and Barry Manilow’s Classic Christmas. Repeat, repeat, repeat. I actually felt bad for my students. I assigned them to copy the vocabulary words, which were all adjectives with -er tacked onto the end, and began to walk around the room. I looked over at Zach in the back left corner, who was uncharacteristically industrious. As I walked toward him, he quickly shoved something in his desk and looked up straight ahead.

“What is it Zach?” Honestly, if I was watching this class I’d be bored too.

“Nothing...” A cheeky grin emerges.

When the bell rang Zach approached me.

“Mr. Loeb, you can’t tell Mrs. Wang (his homeroom teacher) . After all, it’s your fault.”

“Well yeah, I know, but not every class can be fun. I’ve told you that.”

“No! I was working on this.”

He shows me an absurdly intricate drawing of a futuristic looking city. Written on the bottom in Chinese, “My Ideal Hometown.”

This year Sanzhuang’s theme for the CORE (Community Outreach Rediscovery and Enlightenment) project is “My Ideal Hometown.” My two other colleagues and I asked students to get into groups of five with others from their village. The groups would compete for an educational field trip to Yunnan’s capital, Kunming, at the end of the school year. Zach is from a tiny mountain village called Dongpo. Because his academic success has been low, he was apparently not a desirable team member. Because Dongpo is the smallest village of all the feeder towns for Sanzhuang, the other students said they had to take Zach on their team, otherwise they would only have four members.

Zach didn’t let them down. It appeared that all his restlessness and nervous energy in the classroom was being channeled toward the project. Whereas previously getting him to write his own name in English proved an almost impossible task (his favorite version is ScAh), now he was drawing elaborate diagrams of urban plans, and doing so way beyond the expectations of the project.

When half of the remaining 27 teams were eliminated after the first two rounds, tiny Dongpo was still in contention for the trip to Kunming. Zach would come up to me after almost every class asking what the score of the competition was, even though I’m sure he knew each team’s point total by heart. I’d have to tell him, “Zach, we just got back from a holiday. The score hasn’t change in a week.”

Last weekend we tallied the scores. Zach didn’t win. Dongpo placed sixth out of an original group of 30, a rather impressive showing considering they were competing against teams from towns 5 times their size. The winning team was made up of five incredibly motivated girls who, though it’s still early on in the game, look to be very much on track to go to high school, college, and beyond.

But Zach held his own. He may score 70 points lower than them in the classroom, but his team finished a mere five spots below them on the CORE project. And you know what? He was bummed out. He asked me what set the other team apart and why his team didn’t win. Dongpo’s model was great, I said, but the winning team’s written work was exemplary. Every week Zach receives papers full of red X’s, 30 percent test scores, and angry looks from teachers. At this point, he’s learned to shrug it off. But not this time.

Seeing Zach give his absolute all--and then some--got me thinking. Elementary school isn’t about prepping kids for high school and college. At least, it shouldn’t be. School is about giving kids the chance to discover a passion and belief in themselves. Some kids like math, some kids don’t like math but do it because they know they have to. Some kids hate it, can’t do it, and will never change their mind.

That doesn’t mean they can’t be passionate and have confidence about something. That doesn’t mean they’ve missed their shot at a productive obsession. Newton liked gravity, Galileo liked stars, and Zach from Dongpo likes drawing intricate constructions of his ideal hometown. Newton wouldn’t have known how much he loved gravity if an apple didn’t bonk him on the cranium. Zach wouldn’t have known how much he loves drawing if he wasn’t given the opportunity through the CORE project. I mean and believe that with complete conviction. Zach’s not even close to “dumb,” whatever that means, his passions have just been on the shelf.

In the next 10 years, the scale will never be tipped in Zach’s favor to go to college in China. The time, money, and political influence needed to give low-performing kids in rural China a high-level of education just isn’t here. But, if we have the opportunity to move the scales ever so slightly, we should give it our best shot. The students deserve it. Zach deserves it.

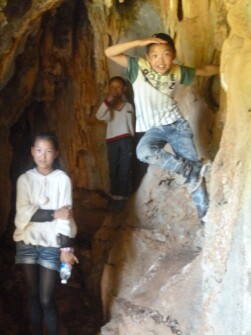

Photos courtesy of Taylor Loeb, Teach For China 2013-15 Fellow