The story so far:

“Interpreter Is Valued Colleague on Reporter’s Journey,” April 14, 2005.

“Top-Ranking Woman Reflects on Role in Jordan’s Education Ministry,” April 13, 2005.

“In Jordan, Days Off Are Time for Religion, Relaxation,” April 11, 2005.

“Friendly Jordanian Hotel Is Home Away From Home,” April 7, 2005.

“School-Smoking Rules Get Hazy in Jordan,” April 6, 2005.

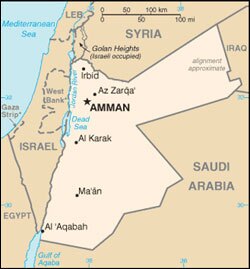

Editor’s Note: Education Week Assistant Editor Mary Ann Zehr is on assignment in Jordan to report on the education system of this strategically located country in the Middle East. During her two-week visit, which began April 1, she will also be filing occasional reports for edweek.org.

I expected the air to be dry and hot, Jordanian women’s Islamic dress to be drab, and school administrators to be polite but distant when I arrived in this Middle Eastern country to write about school reform.

The opposite has been true on all of those points.

Apparently because of a cold front that blew in from Lebanon, the weather has been drizzly and chilly for the first three days of my two-week stay here.

Map of Jordan courtesy of The World Factbook, from the CIA.

I find myself, meanwhile, admiring some of the beautiful accessories and elegant cuts of the Islamic dress of female principals at schools that I’ve visited (and I’m not one who usually pays attention to fashion). And I’ve been humbled by the hospitality of school principals and their staffs. At one school, the staff baked a table full of cakes and made snacks as a welcoming gift for me.

At other schools, principals have repeated both in Arabic and English: “Ahlan wa sahlan,” or “Welcome.” My hard-working interpreter, an Iraqi woman who is an astute observer of Jordanian culture, helps me bridge the cultural divide.

I’ve also been surprised that with every school visit, I find more connections between Jordan and the United States.

Sabah Shiko, the headmistress of the Al-Khansa’a Comprehensive Secondary School for Girls in Jerash, located 45 minutes from Amman, has two daughters living in the United States. She has also visited the U.S. “It’s an advanced country. Personally I like it,” she said, through my interpreter.

Yesterday, on my visit to her school of 900 girls, Ms. Shiko was dressed according to traditional Islamic custom. She wore a floor-length suit. Her carefully pinned scarf covered her neck and every strand of her hair. But the suit was cut from a loosely woven lavender cloth and had large decorative buttons down the front. With 12 inches trimmed off the bottom of the skirt, it could have been worn on Capitol Hill.

Ms. Shiko appeared to be in tune with the needs of her teachers and students. For example, three years ago, she began an effort to provide three meals a day to 70 girls in her school from very poor families. The meals come from parents, teachers, and students who make an extra sandwich or cook meals to share with the girls.

“As a principal, I noticed some girls didn’t go out to the playground,” she explained. “I noticed they were so thin. They didn’t have money to buy food at the canteen or bring food. I thought, they can’t study unless they are fed well.”

I was impressed that in a country in which most school programs are created in the Ministry of Education, she took action to make sure her students were well cared for. At the same time, Ms. Shiko has embraced training initiatives started by the ministry that have helped her teachers improve their teaching methods.

Before I left the Al-Khansa’a School, the teachers led me to an inviting spread of snacks and sweets, including a cake topped with red gelatin and pineapple rings. Unfortunately, I had time for only a bite of cake and a sip of strong coffee—from a cup the size of a shot glass—before heading to the second school visit of a three-day tour of six schools scheduled by the Ministry of Education.

I’ve also found that I must be careful what I ask for because, in a welcoming spirit, Jordanians will try to provide it.

This morning at the King Abdullah School for Gifted Students, in Salt, Jordan, a small city just west of Amman, I mentioned to the principal, Ni’mat Abutaleb, that I wanted to observe a class in the language computer lab. Minutes later, I was led to see the “class.”

I soon learned that the class had been pulled together with 20 7th and 8th graders who were on break. A teacher had been brought in to teach an English lesson on how to express “likes” and “dislikes.” I didn’t really want to report on a class that wasn’t part of the regular schedule for students. So I asked Ms. Abutaleb if I could stop the class and interview the students instead.

Ms. Abutaleb kindly met my request.