| |

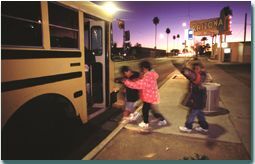

| Buses from Pappas start early in the morning to gather up homeless students from shelters, parks, and rundown motels across Phoenix. |

The first strokes of daylight have just begun to color the Arizona sky purple when a bus from the Thomas J. Pappas School turns the corner and wends its way down a stretch of Van Buren Street notorious for hookers and hoodlums. The bus chugs past an adult-video store and a rent-to-own furniture outlet, and stops to pick up children in front of seedy, inhospitable accommodations with names like the Motel Arizona and the Flamingo Inn.

Such establishments may not be typical bus stops, but Pappas is not a typical school. All of its students are homeless, and the bus they board each morning whisks them from a rootless world of eviction notices and cramped quarters to one where every child who wants one is guaranteed a hot breakfast and a warm hug.

Since its founding a decade ago with a handful of pupils in a church fellowship hall, Pappas now serves 730 students in grades K-10 in two downtown Phoenix facilities.

| |

| The school provides the students with hot breakfast and lunch, and the neediest children get boxes of food to take home to their families. |

With students coming from all over the city, the school regularly reroutes its eight buses to pick up children who have moved from a motel to a shelter overnight. Or from a grandparent’s house to a riverbed.

“The children want to be here,” says Ernalee Phelps, the resource-development director at the school. “If they miss the bus they will call us, sometimes collect, and say, ‘Pick me up.’ This is their one safe and special place to be.”

Over the years, the school’s staff members have learned to anticipate—and stem off with services—a whole range of everyday emergencies that can keep homeless children from coming to school. The school has a clothing room that students can visit once a month to pick up fresh socks and underwear and a change of clothes. Volunteer pediatricians staff an on-site clinic that is always bustling with children getting checked for head lice or receiving immunization shots. School employees even dole out alarm clocks to children who have trouble waking up on time to meet the bus for an epic, sometimes two-hour-long bus ride across town. The clocks are old-fashioned windups, because even basic electricity is not a given in these children’s lives.

“We understand that they have no clothes, no records, nothing,” says Ana Sutton, one of three therapists who provide counseling at the school. “We assume they have nothing and meet them there.”

As a public school that can’t levy local property taxes, Pappas receives roughly two-thirds of its funding through a standard per-pupil allocation from the state, then makes up the rest of its budget through a combination of specialized state and federal grants and community support. The school is designed to be a transitional school—an unchanging place students can anchor themselves to as long as their families’ living situations remain rocky. Under the current policy, students are moved to neighborhood schools once their families are in stable housing for at least four months. Home visits help establish where families are living and whether the children are ready for transition.

Propelled in part by a change in state policy that now requires Arizona parents receiving public assistance to show proof that their children are attending school, the number of students at Pappas has more than doubled in 21/2 years. And the school could have many more students if it didn’t limit the length of its bus routes to a maximum of two hours. In fact, officials are currently making inroads with community members in the southern and western reaches of Phoenix to try to establish new schools that serve homeless children in those communities.

| |

| Rosie Hernandez, above, helps students select outfits from racks of donated clothes. |

With a high-profile reputation for doing good works, the school boasts a list of donors that runs on for pages. Just this school year, the school has already received more than $290,000, through a combination of individual contributions and funds given through the school’s own foundation. That money comes in addition to bundles full of donated clothes and toiletry items, stacks of donated food in an on-site food bank, and the time given by 375 employees from area companies who have signed on as mentors for Pappas students.

There is even a volunteer clown who comes to the school monthly to pass out toys to students who have birthdays.

Diane Marie Silk Caporale says the school and its numerous extras provided a safe haven for her two elementary-age sons last year when she left a physically and verbally abusive relationship and moved to a shelter. The school was able to buy and deliver to the shelter a machine to help her youngest son with his asthma, while her older son received counseling when his behavior got out of control.

“But it wasn’t just the resources, it was also the moral and emotional support,” says Caporale, whose sons are attending a neighborhood school now that their mother has secured more permanent housing. “Pappas was exactly what we needed when we needed it.”

But despite such apparent backing from the community, Pappas has its share of critics.

National advocates for the homeless argue that any school that isolates such children from others is misdirected and violates federal policy. |

National advocates for the homeless argue that any school that isolates such children from others is misdirected and violates federal policy on the education of the homeless. Language calling for the integration of homeless students into neighborhood schools will also likely be strengthened during the expected reauthorization this spring of the Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act, a 13-year-old measure that guarantees homeless children access to a free public education.

A recent report conducted by the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth and the National Coalition for the Homeless concluded that in the 1997-98 school year, states provided education services to roughly 230,000 homeless children. That figure represents only 37 percent of the more than 625,000 homeless school-age children identified, based on information from 46 states, by the U.S. Department of Education in 1997.

Advocates for the homeless agree that the vast majority of those students are educated through various programs in neighborhood schools. Some of those programs do exceptionally well, says James Stronge, an education professor at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Va., who specializes in homeless-education issues. But in others, “it’s a struggle to get the homeless into schools because of barriers to access like transportation, legal issues such as residency, and if a student doesn’t have evidence of appropriate shots,” Stronge says. “And once a child gets into school, there are psychological barriers that can keep them from succeeding.”

The National Law Center for Homelessness and Poverty is scheduled to release a report this week on the 42 schools the center has identified throughout the country that serve homeless children in settings separate from traditional neighborhood schools. But with its myriad resources and traditional classrooms, the Pappas School is unique among schools that serve homeless children exclusively, says Sally McCarthy, a staff lawyer for the Washington-based center.

“The typical separate school is a classroom in a shelter with one teacher assigned to a wide range of grades,” McCarthy says. “A lot of schools don’t follow a curriculum; they don’t have materials. It’s vastly inferior to what kids are getting in public schools.”

Still, McCarthy and other experts on the education of the homeless maintain that even a resource-rich school like Pappas should be viewed through the prism of the U.S. Supreme Court’s historic 1954 ruling on racially segregated schooling. Separate, they say, still cannot be equal.

“Kids who are homeless are just like any other kid,” says Barbara Duffield, an education policy analyst for the National Coalition for the Homeless, based in Washington. "[Pappas] is projecting an image that homeless kids have some kind of cognitive condition tied to the fact that they don’t have a house. It’s extremely dangerous.”

Sandra Dowling, who oversees 58 regional school districts in Maricopa County, Ariz., as the county’s elected superintendent of schools, founded the Pappas School in 1990 after stopping a school-age girl on the street one day and asking her why she wasn’t in school. Since the girl could not provide a birth certificate, immunization records, or a permanent address, traditional elementary schools had refused to enroll her. Neighborhood schools, Dowling maintains, were then and still are ill-equipped to educate homeless children successfully.

‘Who is going to want to track these kids down if they haven’t been in school for two years, have head lice and are filthy dirty?’ Sandra Dowling, Superintendent, Maricopa County, Arizona |

“There’s no [financial] incentive for schools to track these kids down,” Dowling says. “Who is going to want to track these kids down if they haven’t been in school for two years, have head lice and are filthy dirty? Structurally, it’s impossible to be all things to all people.” Besides, school officials say, Pappas wouldn’t be able to offer such comprehensive services to homeless students if the school diluted its mission by opening its doors to others. And when so many of the area’s neediest children are in the same place, officials argue, it makes it easier for community members to be charitable.

“People won’t send clothes if they think the clothes are going to go to his daughter,” Dowling says, motioning toward a district employee. “That’s why you can’t mainstream [homeless students]. You can’t focus the public support.”

The school’s staff members have also seen firsthand how the educational efforts of even the most well-intentioned neighborhood schools can falter in the midst of the peripatetic lives of most homeless families. Last year, the school transferred to neighborhood schools 70 students whose families had been living in a stable place for at least four months. A whopping 82 percent of those students have already landed back on Pappas’ doorstep.

What’s worse, many of the students had virtually no schooling in between leaving to attend a different school and coming back to Pappas, despite the fact that Pappas administrators had made sure they were registered elsewhere. Registering does not necessarily translate into attending.

Even if homeless families have held one address for several months, administrators say, just one spell of bad luck—a lost job, a broken-down car, a sudden illness—can put them out on the streets again.

When that happens, a child will either switch to yet another new school or stop going altogether.

The high boomerang rate “is not our fault, and it’s not the public schools’ fault,” Dowling says. “It’s the fault of the circumstances these kids are in.”

For students used to bouncing from school to school with every shift in housing, Pappas offers a strange paradox: The more their families move around, the longer they’re qualified to stay at the same school. And while much of the school’s population is in flux—with students literally coming and going with a change in the seasons—a core group of pupils has remained at the school for years.

Anthony McClure, now an 18-year-old community college student, attended up to four or five different schools each year while growing up in a chronically homeless family. He says it wasn’t until he was attended Pappas for two straight years, from 6th to 8th grade, that he was able to make a friend.

“I met him in 6th grade, and we’ve been friends ever since,” the soft-spoken McClure says.

While critics argue that the homogeneous environment at Pappas isolates homeless students, McClure says it was a relief to know he was with other children who were going through what he was.

“Before, I would always try to hide my situation,” McClure says. “But then you come to a school like this and you feel better. You know everybody is the same, and so you have nothing else to worry about.”

That shared knowledge of homelessness and poverty is a steady, unshakable undercurrent at a school that, at first glimpse, looks much like any other.

Youngsters jump joyfully on new playground equipment at recess time, even as their teacher digs in her purse for lip balm to soothe their chapped lips. Students dutifully hunch over their worksheets even as a school aide stands at the door, flipping through an envelope full of requests for donated clothing.

And then there are the stories. Stories like the one Dr. Susan Stephens-Groff tells of the boy who functioned normally for six days with a ruptured appendix before the school’s medical staff realized his afternoon naps were an indicator of something more serious than sleepiness.

“He didn’t tell us he had belly pain,” says Stephens-Groff. “He just came in here to sleep.”

A pediatrician who volunteers at the school’s clinic once a week, Stephens-Groff said that particular child’s particular brand of stoicism is not unusual at Pappas. Unlike some children who cry over every bump or bruise, she says, the students at this school aren’t much for complaining. And while the doctors at the school tend to treat a lot of the conditions that come with living in crowded, unhygienic conditions—head lice, skin infections, conjunctivitis—they also see the bone fractures and ear infections common to more routine childhoods.

| Nurse Eileen Smith, above, comforts one student while discussing another’s symptoms. Lice, asthma, conjunctivitis, and other ailments are common. |

“It’s like normal pediatrics, but to the extreme, because the problems go untended for so long,” Stephens-Groff says. “One kid had a broken bone in his shoulder and walked around cockeyed for days.”

By the time Pappas students reach adolescence, another byproduct of their homelessness is anger. Corinne Frank, a teacher of students with emotional disabilities at Pappas’ upper school, says she has learned that she often can’t effectively teach her students until they have vented their frustrations.

Just in the past few weeks, she’s had to deal with a 13-year-old boy who had been left alone in a hotel room all night and didn’t know where his mother and brothers were, a girl distraught over her mother’s drinking binge, and a student who had overdosed on prescription drugs.

“You have to put out a lot of fires,” says Frank, a veteran teacher who has been at Pappas for seven years. “You’re not going to get to multiplication or division until you’ve talked it through and gotten them to a place where they can move on.”

At the elementary school, the younger students’ emotions often come out in subtle ways. Amid the colorful stacks of donated books in the school’s elementary library is a laminated booklet filled with essays by Pappas students that detail what they would do as president. Pragmatic plans to “build more shelters” and “give everyone a new home” easily outnumbered schemes involving Pokémon and other toys.

And on a recent afternoon in the school’s clothing room, the room’s director, Rosie Hernandez, is dropping new socks and underwear into large garbage bags held open by four chattering kindergartners, when she is interrupted by a teacher who walks in with a pupil who has just wet his pants. It is the third such emergency clothing change that Hernandez has dealt with in half an hour.

Accidents like these, it seems, are woefully common at Pappas.

“Sometimes it’s a lack of social skills; sometimes they just forget,” says Phelps. “Sometimes they’re traumatized, and that’s how it comes out.”

In the midst of such everyday crises, Pappas teachers have learned how to cope. Fifth grade teacher Ivi Tihkan says she purposely designs her lessons so that they never extend beyond one day, and she reviews material frequently. She estimates that more than 100 students passed through her classroom over the course of last school year, and only one-third of the students who started the year at Pappas were still around in June.

Often, she won’t even be able to say goodbye to a student who may be in the classroom one day and unexpectedly gone the next.

“A lot of these kids are intelligent, but they’re so educationally deprived,” says Tihkan. “You have to try to have closure every day.”

Perhaps it is a similar need for closure expressing itself when students and teachers trade hugs during a routine Wednesday school dismissal. Kindergarten teacher Cynthia Gulley has even pulled up a chair alongside the waiting school buses to see that, one by one, her students get safely on board. She ties untied shoelaces and reminds a girl dressed in a flimsy sundress to wear her winter jacket tomorrow.

Surrounded by a swirl of students carrying bags of clothes and boxes of food, Gulley plants a kiss on one student’s cheek, whoops “I got me some sugar, baby!” and sends the student into peals of laughter. In class, however, Gulley says she is sure to warn her students of the dangers of strangers since, as she puts it, “these children will hug a stick.”

| |

| Kindergarten teacher Cynthia Gulley embraces one of her students. |

With children this needy and teachers this compassionate, Dowling, the Maricopa County superintendent, says she has had to set limits.

Last year, the school’s then-principal adopted a 6-year-old who had been abandoned by her mother. This year, Dowling says, she has felt concerned about the burnout that can occur when staff members don’t put emotional distance between themselves and children in desperate circumstances. She has made it a policy that school employees shouldn’t drive students in their personal cars or take students home.

For their part, Pappas staff members say they couldn’t keep going if they didn’t maintain a laser-like focus on the needs of the students.

“If I didn’t focus on the kids, I’d get bitter,” says Mary Michaelis, who handles student enrollments and withdrawals for the school. “We might be enabling their parents, but they are the same parents who wouldn’t otherwise have their kids in school.”

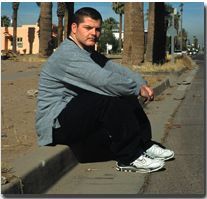

Teachers trying to explain what keeps them hopeful enough to stay at the school often cite Chuck Bacon’s name. |

Teachers trying to explain what keeps them hopeful enough to stay at the school often cite Chuck Bacon’s name. That could be a sign of how few are the success stories at Pappas, or it could be a tribute to Bacon himself.

Now a senior at the nearby Carl Hayden High School, Bacon is taking enough credits to earn a diploma while working full time as an aide at Pappas. The husky 18-year-old says he “took, took, took” during his four-year stint at Pappas. Working at the school is his way of giving something back.

| |

| Chuck Bacon, 18, graduated from Pappas and works there while the completes his high school diploma. He plans to start college in the fall. |

Bacon came to Pappas in 5th grade without having ever set foot in a 4th grade classroom. His family had simply moved around too much that year for him to attend school.

But once he started going to Pappas, Bacon says, he did his best to stay there. He remembers mornings when he and his younger brother would spend the night in a field, then wake up and use the restroom of a gas station to wash up before coming to school. Pappas at the time didn’t have the shower and medical facilities it now offers, but it did have people who cared.

After breaking away from his family at age 13, Bacon bounced from one friend’s house to another and learned to fend for himself. He left Pappas after 8th grade to attend a traditional high school and, by his junior year, secured housing with a sympathetic former teacher who said she would offer him free room and board as long as he stayed in school.

Thanks to a college-scholarship fund set up for former Pappas students, that’s a bargain Bacon plans to keep. He intends to start community college in the fall, and eventually, become a teacher.

“This staff will bring things out of you that you don’t know you have,” Bacon says. “It’s hard to fail when you have nine or 10 people behind you saying that’s just not possible.”

Outfitted with a CB radio linked to eight bus drivers and a cell phone that never stops ringing, Carol Houselog every afternoon tackles the Herculean task of coordinating bus pickups and returns for Pappas students.

When parents call in to say they’ve moved overnight, or send their children in with a note, Houselog processes the information and then reroutes her bus drivers accordingly. She coordinates about four or five route changes per day, processing more changes on Mondays and many more over an extended break.

Because parents don’t always take responsibility for informing the school of their moves, some Pappas students will miss a day simply because the buses don’t know where to find them. The school used to routinely send a van out to pick up stragglers, but cut back on the practice when some parents began to abuse the system—using the van as a de facto school bus that allowed them to sleep in longer.

| |

| Because parents move so often, at day’s end children may be directed to take a different bus route back than the one they rode in on. |

At the end of the day, the buses line up in front of sidewalks painted with colors corresponding to the names of their bus routes. During the chaos of dismissal, Houselog says, teachers and aides often have to remind a student who has moved to head for a bus by the yellow marker instead of the bus by the blue marker, or vice versa.

The work can be overwhelming, rewarding, and frustrating all at once, but like other staff members at Pappas, Houselog says she wouldn’t change it for anything.

“There’s something about watching the buses roll out of here, with all the kids’ faces pressed against the windows,” she says. “I get this feeling it’s what I should be doing.”

Photographs by Benjamin Tice Smith