For more than 10 years, the education community has watched the corporate ups and downs of Edison Schools Inc., the New York City company that has roiled the waters with its aim of making money from public schools. Long a target of those wary of such aims, the now privately held Edison made headlines with its four-year run as a public company, turned a profit in 2001, and later saw its stock price sink to less than $2 a share.

Far less attention has been paid to what Edison schools actually do that makes them distinctive. It turns out that the company insists on spreading leadership widely in a school—a notion that is gaining traction among policy experts.

“The concept is, a school needs a leadership team,” says Chris Whittle, Edison’s chief executive officer. “A lot of public schools don’t really believe that. They think all they need is a terrific principal. But they need a whole team to drive a school to excellence.”

| |

| (Requires Macromedia Flash Player.) |

Edison’s leadership model prescribes how that team should look and function. And, according to a recent study for the company by the RAND Corp., when the design is faithfully followed and free from constraints, such as teachers’ union contracts, students in Edison schools academically outperform those attending comparable traditional public schools over time.

Because Edison has operational control of its schools, says Brian P. Gill, the lead author of the study, it can establish continuity that often escapes conventional schools, which can fall victim to shifting political winds and changes in priorities. “The model Edison espouses and aims to get involves a pretty comprehensive management approach that includes a range of incentives and accountability mechanisms that aren’t often seen, at least as a package, in conventional public schools,” Gill says.

The key, according to Edison’s corporate bosses and the educators in its schools, lies in developing a shared vision that is followed by the team.

At Gilmor Elementary-Junior Academy here, Principal JoAnn Cason sums the philosophy up this way: “It’s not about me seeing it. I’ve got to get others to see it, too. I can’t do this by myself—puh-leeze.”

At Gilmor—a pre-K-6 neighborhood school across from a public-housing project serving 545 African-American students—the leadership team helps Cason continuously demonstrate and reinforce her vision and the instructional practices that she and, more importantly, Edison believe will best serve her students.

James P. Spillane, a professor in the school of education and social policy at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., says creating a formal structure and routines to support and foster leadership, as Edison has done, is essential to make collaboration successful and meaningful. In academic circles, the idea is known as “distributed leadership.”

“It’s not just saying, ‘We will distribute leadership,’ ” adds Spillane, who is heading a major research project on the topic. “You have to make it happen.”

Edison, founded in 1992 by Whittle, takes a methodical and specific approach to leadership and collaboration in its schools. The nation’s largest for-profit manager of public schools currently runs 136 schools—including charters—enrolling about 53,500 students.

Schools divide their teaching staffs into “house teams” of about six teachers. Among that group is a lead teacher, usually a high-performing instructor, who runs meetings, models teaching, handles student discipline for the team, and, depending on union contracts, supervises teachers. Edison’s school contracts dictate the scope of responsibilities assigned to lead teachers, whose positions typically earn them a $3,000 annual stipend on top of their regular pay.

House teams meet daily for 45 minutes. Teachers have an additional 45-minute planning period each day—a benefit made possible by scheduling art, music, and drama classes for students.

An extensive in-house professional-development program, created by Edison, provides principals and lead teachers with specific strategies for working as a team. Required off-site weeklong training sessions offer courses on a range of topics, from leadership to interpreting student data. And every school meeting includes professional-development elements or is a training session in itself.

In turn, Edison principals, like Cason, run their schools with the assistance of a trio of players who are responsible for a number of schools in a region that sometimes span different states. Each principal is supervised by a general manager, who holds the principal responsible for meeting the company’s academic and financial goals. The achievement vice president is a principal’s mentor and coach, providing hands-on guidance on instruction and analyzing test scores. A financial manager frees the principal from handling day-to-day money matters and helps meet the principal’s budget priorities.

|

A principal’s experience, strengths, and weaknesses dictate how frequent interactions are with the upper-level managers, each of whom works with up to eight schools. John Chubb, Edison’s chief education officer, says it’s critical for principals to foster high levels of collegiality and to share decisionmaking. But that can only be done, he says, if they themselves have freedom. That autonomy is granted in exchange for higher levels of accountability; strong leaders reap lucrative financial rewards in the form of bonuses of up to $30,000. Those who fail to measure up don’t have their contracts renewed.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say that the most important factor in determining a school’s success academically is if they come together as a team,” Chubb says.

The reverse is also true, the RAND study noted, since Edison schools that are struggling with the management model posted smaller gains.

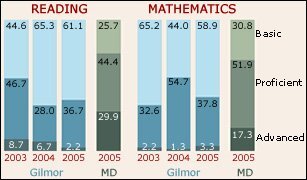

In 2000, Edison was invited by the state of Maryland to manage Gilmor, Montebello, and Furman Templeton elementary schools in Baltimore. Using a 1994 “reconstitution” policy, the state board of education voted to seize control of the three schools. Gilmor had posted the state’s second-worst scores, and all three scored in the bottom 10 percent of elementary schools in reading and mathematics across the state.

The growth rates of all three schools rank them in the top 30 percent of Maryland elementary schools, according to the company’s statistics. But some critics contend that the Edison Baltimore schools’ scores, in some subjects and at some grade levels, are merely on a par with, and sometimes trail, the results for other schools serving comparable percentages of poor and minority students.

Nancy S. Grasmick, Maryland’s state superintendent of schools, bristles at those comparisons, which she says don’t take into account the long history of “extremely low” performance at the three schools.

“To have these schools accelerate academically so quickly is amazing,” Grasmick says.

Grasmick successfully lobbied to extend Edison’s contract to 2007. But changes to the state’s accountability plan under the federal No Child Left Behind Act mean the company’s future will rest with the Baltimore school board.

Under Edison, the changes at Gilmor ranged from academic to physical—bare light bulbs hung in the hallways and carpets were infested with insects when Edison arrived.

Edison principals are responsible for ending the year “on budget,” which includes meeting agreed-upon enrollment numbers and revenue targets for some schools. In addition, students are expected to be 100 percent proficient within five years, starting when the company arrives.

Over the years, Gilmor’s academic highs and lows have taken an emotional toll on Cason. She earned a $20,000 Publisher’s Clearinghouse-sized cardboard check at a glitzy, 2002 Edison event in Colorado Springs, Colo., to recognize schools and principals that met their financial and student-achievement goals.

But Cason’s memory of that night fades and her eyes well up with tears when she discusses Gilmor’s failure to make the adequate-yearly-progress mark—a crucial measure of success under the No Child Left Behind law—for the 2003-04 school year. The school also missed the company’s academic goal by one student and the enrollment target by a handful of children that same year.

At Gilmor, roughly 50 percent of students are proficient in both reading and math at all grade levels. Edison is requiring a gain of 8 percentage points this year, compared to about 5 percentage points to meet the federal law’s targets.

Cason, who is in her 40s and has almost two decades of experience as an educator, was recruited by Edison to take on Gilmor—a school where she had briefly served as the assistant principal in 1992. Quick to acknowledge that she leaned heavily on her own charisma to lead previous schools, Cason now says she relies on her team and her support network.

“In this design, there’s no reason for you to be isolated,” she says.

Zelda Holcomb, Edison’s vice president of operations for the Baltimore schools, acknowledges that Cason takes the school’s ratings personally. “I told her: ‘I know as your supervisor how hard you work, but there is something missing—or we wouldn’t miss the targets,’ ” says Holcomb.

They sifted the test-score data together with Sarah Horsey, Edison’s academic vice president with oversight for Gilmor, looking for areas of improvement. Special education students and children on the cusp of making the grade are given added attention, for example.

“We’re trained to be active listeners and to use data in a persuasive manner,” says Horsey, a former principal of a Baltimore Edison school. “We try to get the principals to see what the data is saying to them.”

Despite the setback in 2003-04, Gilmor made its AYP targets last school year. This week in San Francisco, Cason, who earns $109,000 a year, is scheduled to receive a check in excess of $20,000 for meeting Edison’s goals.

Gilmor’s leadership team gathers daily at 7 a.m. for a “stand-up” meeting. Still in their coats, laden with heavy tote bags and books, teachers crowd around a small table in Cason’s office to pick up memos and hear about the day’s priorities. No one sits down. There just isn’t time.

Just as the teachers seem poised to leave, Cason—or “Doc,” as the staff calls her as a nod to her doctorate in education—draws a square on the huge whiteboard leaning against the wall.

“Who’s ultimately responsible in the classroom?” Cason asks, her hazel eyes searching faces for a response. “The teacher,” the leadership team members respond, almost in unison. Cason draws a small circle, representing the teacher, in the square—her classroom.

The principal also takes a moment to help lead teacher Eleanor Rosendale, who is new to the position and unsure about how to assist a teacher who struggles to prepare her classroom adequately for the next day’s lessons. Colleagues chime in with advice: Have the teacher observe a model classroom. Help the teacher set priorities for her time. Cason nods in agreement, her reddish-brown dreadlocks swinging back and forth. “I’m not asking you to do it for her,” Cason stresses to Rosendale.

These quick sessions are one way Cason interprets Edison’s emphasis on continuous leadership development, shared decisionmaking and problem-solving, and accountability. But there are many others.

Once a week, Gilmor’s seven lead teachers gather with the principal and other key staff members after school for a weekly leadership-team meeting where they evaluate programs, monitor student achievement, and set policies. Gilmor’s team has 15 members, including the head of building services, out of a staff of 52.

Later, during a “house team” meeting, lead teacher Fahmeeda Hassan tries to engage teachers in discussions on homework policy and strategies for promoting “positive self talk” in the classroom. Two teachers who are new to the school remain silent, while a former lead teacher eagerly raises her hand to answer every question.

“You have to find their talents,” Hassan, who teaches 4th grade, observes later. “And know when not to push them.”

Emily Hunter, Gilmor’s academic coordinator and a member of the leadership team, says it’s difficult for some teachers to adjust to Edison’s emphasis on accountability in addition to the school’s challenging population.

A veteran teacher resigned after just a few weeks at Gilmor this year, and last month, a young teacher, concerned that he was failing as an instructor, started packing up his classroom without a word to Cason. (The principal, along with a lead teacher, persuaded him to stay after pledging their support and tutors for some of his students.)

Hunter, 29, says she was headed to law school before joining Edison. Now, the former lead teacher wants to be a principal. In conventional public schools, she complains, “it’s all about seniority and not about ability” when promotions are considered.

But not all educators thrive on the daily meetings and continual feedback. At times, the approach is viewed as redundant and even unnerving.

Teacher Desmond Beach keeps his cool when Cason makes an unannounced “five-minute walkthrough” during his lesson about drawing a self-portrait. Her clipboard in hand, Cason notes that Beach should engage his students more by having them read the objectives aloud. She also wonders where his pointer is, and compliments his energy. All this is put in writing and will be placed in his personnel file.

The following day, lead teacher Kyra Daley relays Cason’s comments to Beach. The first-year Edison teacher receives the feedback well, but admits that while the “pop job reviews” keep him on his toes, sometimes he wishes that he could be left alone to teach.

Cason says lead teachers like Daley and Hassan guarantee that Gilmor would continue to make progress if she were to leave. “I don’t make a difference like that,” she says. “It’s not built on me.”