Summertime news out of Washington, matching the weather, has been hot, even steamy.

Immigration reform imploded. The nation’s attorney general still sizzles in a widening scandal. A conservative U.S. senator from Louisiana, in the stickiest story, admitted to “a very serious sin” somehow linked to an escort service.

But a more consequential story attracted little coverage: Democratic support of the No Child Left Behind Act fractured badly.

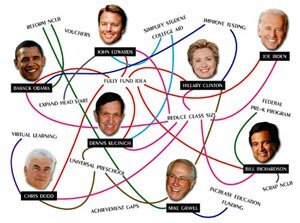

Sen. Hillary Clinton, D-N.Y., a presidential candidate, struck first and directly at the holy grail of NCLB’s standardized testing. “It’s time we had a president who cares more about learning than about memorizing,” Sen. Clinton said before thousands of cheering New York state teachers in April. “The tests have become the curriculum instead of the other way around.”

Then a national poll , released by the Educational Testing Service in June, revealed simmering voter disaffection with the federal education law, prompting sharper attacks by the candidates. Americans, we learned, are deeply divided over how the law is being implemented while still backing its virtuous, pro-equity aims.

—Sarah Evans/Education Week

By early July, Sen. Barack Obama, D-Ill., also a candidate for the nation’s highest office, said in a speech to the National Education Association’s convention in Philadelphia that, if elected, he would fix “the worst aspects of No Child Left Behind.”

Sen. Obama repeated his stump-speech line that President Bush had left “the money behind.” Then he went further, promising to right the law’s imbalance between rules and resources, “giving teachers the support that they need.” He argued that current policies do little to improve the daily work lives of teachers.

Back on Capitol Hill, some weren’t so cheered by the sudden Democratic thrashing of their legislative legacy. “No Child” stalwart Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, D-Mass., delayed taking up the law’s reauthorization. “Kennedy now has three presidential candidates on his [education] committee, and they are all increasingly critical of No Child Left Behind,” explained the NEA’s policy director, Joel Packer.

The chairman of the House education committee, Rep. George Miller, D-Calif., pulled first-term Democrats together in June, announcing nine adjustments to the No Child Left Behind law. “He’s met with a ton of members,” one senior Hill aide reported, “to share what he’s hearing, to get their thoughts.”

Rep. Miller, a “No Child” hawk over the past five years, emerged with a more open mind by late July. “The American people have a very strong sense that the No Child Left Behind Act is not fair. That it is not flexible. And that it is not funded. And they are not wrong,” he said in a National Press Club speech.

But as the suddenly fluid congressional debate over No Child Left Behind merges with the campaign trail—offering candidates a platform for punctuating broader themes of federal activism, or how Americans should think about children’s development—will their rhetoric yield sound ideas for improving Washington’s role in school reform?

Some analysts say no, claiming that the Democratic candidates are simply selling out to the unions. “It’s no surprise to see presidential candidates pandering to contributors,” wrote the columnist Ruben Navarrette Jr. soon after the NEA convention.

It’s a convenient storyline. And Sen. Clinton is largely echoing three ideas pressed by the teachers’ associations: class-size reductions, higher wages for teachers, and new preschool jobs for union members.

But deeper forces are at play.

To win the White House, Democrats must attract independent middle-class voters; a few more office-park dads and energized youthful voters would help as well. This is how Democrats regained control of Congress this past November.

The prolonged and ultimately futile immigration debate was a major distraction, bumping Democratic leaders off their preferred pitch: soothing middle-class angst by reducing college and health-care costs, even back-stopping pension plans.

Democrats and independents are far more worried than Republicans about how the No Child Left Behind law may be distorting teaching and learning via a perceived obsession with standardized testing. The more voters associate the education law with President Bush, the less popular it has become.

Yet parents and voters still support a strong federal presence in the struggle to improve schools. Nearly three in five would like to see Washington set uniform curricular standards, according to the ETS poll. Perhaps those responding to the poll had been reading about how many states set their “proficient” achievement bar about two inches off the ground.

The problem with some Democrats’ tight embrace of the middle class is that Washington’s historical focus on educational equity is beginning to blur. Take Sen. Clinton’s proposal to reduce class sizes. It worked in Tennessee, when focused carefully on poor children. But California’s achievement gaps are as wide as ever, after almost a decade of smaller classes. Why? Many strong teachers fled their urban schools for the leafy suburbs.

Likewise, Sen. Clinton’s pitch for universal preschool may yield regressive effects. She aims to subsidize over 3.2 million 4-year-olds, according to a blueprint sketched at a Miami Beach elementary school in May. But almost 90 percent of preschoolers from well-off families already attend local centers supported by parental fees. So, much of the senator’s $10 billion-plus program could aid those who can afford preschool, one reason California voters rejected a similar scheme last year.

As the suddenly fluid congressional debate over No Child Left Behind merges with the campaign trail, will the Democrats’ rhetoric yield sound ideas for improving Washington’s role in school reform?

“If it [preschool aid] were to come to pass, there would be some level of targeting on poor families,” Mr. Packer predicted. Clinton policy adviser Catherine Brown was more direct. “I didn’t say middle-class people would be subsidized,” she said, consistent with Clinton’s new preschool bill that focuses on low-income families, although at odds with her broader campaign pitch.

It’s Sen. Obama who is staking out the most pro-equity position, as Sen. Clinton drifts to the political center. His NEA speech hammered on inequality. As one adviser put it, the Illinois senator wants to “make sure that kids in low-income communities have an equal shot at having a fully qualified teacher.”

“Absent resources for universal preschool,” the aide continued, “Obama’s record in the Senate emphasizes helping children in poor communities.”

Another force undercutting support for the law is the lack of discernible gains in student achievement. Federal officials track children’s progress in two subjects—reading and math—in three grade levels. Since the law took root in 2002, just one of these six trend lines has inched upward: 4th grade math. The other five have gone flat, or gone south.

The diminishing count of stay-the-course NCLB proponents was buoyed in June, when a new report detailed how state test scores have climbed since 2002. But these alleged gains have yet to be detected by the more consistent National Assessment of Educational Progress. Achievement gains were often stronger during the 1990s, as state-led accountability efforts matured, than they are now, with the flattening trend lines of recent years.

The life expectancy of the No Child Left Behind Act may come down to how 42 first-term House Democrats interpret the forces at play. Many are from swing districts populated by moderate, independent voters, including Rep. Jerry McNerney, D-Calif., who recently caught an earful from educators in California’s blue-collar Central Valley.

After patiently listening to a barrage of concerns about the law—ranging from Washington’s lopsided emphasis on penalties, with few supports, to the stifling “culture of testing,” as one teacher put it—Rep. McNerney responded. “There are lots of concerns with where we are with No Child Left Behind,” he said. “It’s going to change.”

Still, these rookie Democrats must demonstrate to their constituents that Congress is accomplishing something. Stalemates over immigration and health care, not to mention Iraq, remind voters of how divided the nation remains, rather than showing them how Democratic leaders can decisively move America forward.

In this light, bipartisan agreement on a revamped No Child Left Behind Act could boost the Democrats. Well, except for the Democrats running for president. They may prefer to set their own colorful reform ideas against President Bush’s gray, disappointing implementation of No Child Left Behind.

In turn, a strong Democratic ticket at the top, attracting broad support from the middle class, could lift the fortunes of congressional rookies as well.