U.S. still feeling academically inadequate in face of evolving global competition.

The miles that separate Ohio from Singapore and other countries rapidly developing into economic and education success stories have all but evaporated over the past decade for policymakers and educators trying to solve the complicated school improvement puzzle.

Hard-hit by global economic pressures that have closed companies and sent thousands of jobs overseas, once-parochial states are beginning to look abroad for answers to their challenges in business, industry, and education.

As leaders in Ohio and other states start to reassess the knowledge and skills needed to succeed in a competitive economy, they are weighing plans to gauge how their schools measure up against those of Singapore, South Korea, and Japan, as well as Finland and other European nations—all perennial leaders on international assessments.

Ohio is ahead of most states in efforts to benchmark its performance against that of high-performing countries, although it has met hurdles in doing so. Yet a growing number of education and policy groups suggest that such cross-nation comparisons are essential.

Their concern: Academic gains made by competitors halfway around the globe will jeopardize the United States’ future economic prospects. Such warnings echo the alarms set off a quarter-century ago this week, when a federal commission issued A Nation at Risk, the landmark—and still-controversial—report that declared a “rising tide of mediocrity” in U.S. education posed a threat to America’s prosperity and status in the world.

“We are now members of a global community, and like it or not, we are not among the top-performing countries in the world,” said Gene Wilhoit, the executive director of the Council of Chief State School Officers.

Disparities in student achievement between the United States and other countries, he added, have shifted the focus from state-by-state comparisons to “concern about those countries that are growing at a fast pace and with relatively high achievement.”

Shifting Threat

A Nation at Risk was released April 26, 1983, by the National Commission on Excellence in Education, a body convened by the U.S. Department of Education under President Reagan’s first secretary of education, Terrel H. Bell.

The strongly worded report touched a nerve among a public weary of a lingering economic crisis and deeply worried by foreign competitors. It cited Japanese efficiency in auto making, a South Korean breakthrough in steel making, and the displacement of American machine tools by German products as signs of “a redistribution of trained capability throughout the globe.”

The report fueled an already-emerging campaign for improving schools as a step to a brighter future for the United States.

Within two years of its release, nearly all states reported that they had raised graduation requirements and adopted statewide assessments, according to an Education Week survey at the time. Over the next decade, most states joined the movement to set academic standards, guidelines that defined what students should know and be able to do in core subjects at various stages of schooling.

Accountability systems soon followed in many states and became mandatory and more extensive under the federal No Child Left Behind Act, signed into law by President Bush in 2002. Many states also have beefed up high school courses and increased graduation requirements nearly to the levels recommended by the commission: four years of English and three years each of math, science, and social studies.

“The report had a remarkable impact in the education field, … and I think it still has a lot of salience today,” said Christopher T. Cross, the chairman of Cross & Joftus, a Bethesda, Md.-based consulting firm, and a former assistant secretary of education under President George H.W. Bush. “We are still faced with an enormous international challenge.”

Now, newfound anxiety has emerged over the perceived educational challenges posed to the United States by China and India, as well as smaller countries that have gained reputations for educating top-level engineers, mathematicians, and scientists.

Although China and India, ironically, do not take part in the international exams of science and math that have caused American leaders so much angst, the United States lags behind many other industrialized nations on such comparisons. And too few students, some policy experts say, can demonstrate proficiency in core subjects on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Even as it’s gotten harder to earn a diploma, large proportions of students who go on to college are still deemed unprepared. Meanwhile, high school graduation rates have been falling.

Some researchers have argued, however, that A Nation at Risk greatly overstated the weaknesses in the American education system—and paved the way for exaggerated worries about global competition that continue to this day.

The scholars point out that U.S. students’ achievement in math on NAEP has steadily improved, even as greater numbers of minority students and English-language learners entered the nation’s classrooms. America’s economy has enjoyed a quarter-century of mostly steady economic growth, and the country continues to rank No. 1 among 131 nations on the economic-competitiveness index set by the World Economic Forum.

International comparisons, those experts say, don’t fairly gauge differences in the educational missions and approaches of participating nations, or even among the student groups tested. Some of the nations that outscore the United States on international comparisons have more homogeneous student populations, they note.

And the relationship between a country’s student achievement and its economic prosperity remains a subject of scholarly debate.

Even advocates of a more global approach admit that the current fixation with the economic rise of China and India tends to gloss over or ignore the flaws in those nations’ education systems, such as the inferior schooling provided to a majority of youths, the grueling exams that dictate students’ secondary school options, and the lack of second chances for those who are motivated to continue their education beyond the traditional age.

Just six in 10 Indian adults, for example, are functionally literate. Only four in 10 youths in India make it to high school, and fewer than one in three of those finish the last two years.

“The China and India threats, while real, are overstated,” Mr. Cross said. “Where they really have us is in the power of their large numbers.”

The authors of A Nation at Risk also misconstrued pre-1983 trends on national test scores and on the SAT college-admissions exam as evidence of declining student achievement, Richard Rothstein, a research associate at the Economic Policy Institute, a Washington think tank, argues in a recent essay. The report overlooked positive trends in participation and improved performance among minority students, he says.

U.S. economic productivity is more likely to be influenced by American monetary policies and institutions than by the performance of its students, he adds. While U.S. policymakers should strive to improve academic performance, especially among low achievers, Mr. Rothstein contends that Americans “should approach fixing a system differently if we believe its outcomes are slowly improving than if we believe it’s collapsing.”

His essay, published by the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank in Washington, suggests “we owe the latter, flawed assumption to A Nation at Risk.”

Rethinking Knowledge

Yet many observers say the changes prompted by the report have resulted in progress. A federal study of high school transcripts, released last year, found that today’s students are earning more credits and higher grades, taking more high-level math and science courses, and completing a more rigorous curriculum than did their counterparts in 1990.

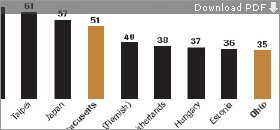

Researcher Gary W. Phillips compared U.S. students’ performance against that of international students by statistically linking an American test, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, with an international one, the 2003 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study. The chart shows how 8th graders in a few U.S. states rank on a common scale with their foreign peers.

SOURCE: American Institutes for Research

** The chart above should have made clear that the U.S. nationwide scores were based on estimates of American students’ proficiency on the 2003 TIMSS. The scores for individual U.S. states listed on the chart were taken from NAEP.

At least 30 states have agreed to revise their high school standards to align with the knowledge and skills students need to succeed in college and the workplace. Of those states, 23 have begun to adapt the standards of the American Diploma project, run by Achieve, a Washington-based organization led by governors and business leaders that promotes higher academic standards. Seventeen states now require students to take a college-preparatory curriculum, which includes four years of math classes, including Algebra 2, although 11 of the states allow students to opt out of the more rigorous track, according to an Achieve study.

Like Achieve, the CCSSO, Mr. Wilhoit’s organization, is working with states to promote college-readiness standards, setting higher-order skills for students such as critical thinking and applications of knowledge, and to encourage international-benchmarking projects.

Despite such efforts, American schools need to do better, many education experts say.

The end of the Cold War, the growing economic and educational opportunities in the developing world, and the changes wrought by technology present challenges unanticipated in 1983, according to Vivien Stewart, the vice president for education at the Asia Society, a New York City-based organization that promotes cross-cultural understanding.

“Now, in the global and digital age, we need to rethink again what are the key things people need to know and be able to do,” Ms. Stewart said. “In a globalized environment, the relevant standard is not the standard of the city or state next door, but the global standard.”

U.S. policymakers are paying increasing attention to the education practices of some countries.

India, for example, has long emphasized a rigorous math and science curriculum beginning in the 1st grade. Singapore has earned a reputation for its uniform standards, syllabuses, assessments, and textbooks aligned to them. Finland has a highly skilled teacher corps and an effective system of identifying and helping students who fall behind their peers. China has emphasized increased access to education across its massive population, and has sought in recent years to replace rote teaching and curriculum with lessons that emphasize creativity and applied skill.

Ohio’s Needs

Two years ago, Ohio decided to look beyond its immediate neighbors, when the state board of education asked Achieve to compare its K-12 system with that of other nations.

“A high ranking within the United States is no longer enough in a globalizing economy,” the authors write in the report, released last year, “and Ohio continues to fall short when evaluated against a world-class standard.”

The report cites “best practices” from around the world, including teacher evaluation in New Zealand and the Canadian province of Ontario, school finance policies in Victoria, Australia, and support for new principals in England. It recommends how Ohio could adapt those models and others from Singapore, Scotland, and China.

The document also calls for the state to set higher academic standards in high school, including statewide end-of-course exams.

Mitchell D. Chester, a senior associate superintendent with the state education department, said several of the proposals are still under review.

Reaction to the recommendations has been positive, but state leaders are likely to tailor the report’s suggestions to what they see as Ohio’s specific academic and workforce needs, said Susan R. Bodary, a one-time aide to former Ohio Gov. Bob Taft.

“While we certainly want to increase skills in science and math, we want to do that in ways that bring forth the inventive and creative problem-solving that is an American hallmark,” Ms. Bodary, now the executive director of EDvention, a consortium at the University of Dayton focused on science- and math-related-workforce policy, wrote in an e-mail.

The Right Approach?

In addition to Achieve, the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers are exploring how states might align their academic-content standards and tests with the best in the world. They’re also encouraging states to sign on for international assessments.

“Many governors don’t just want our kids to compete with kids in Singapore—they want to know what our kids know compared to what the kids in Singapore know,” explained Dane Linn, the director of the NGA’s education division. “We need fewer, clearer, higher standards,” he added, but “we need to simultaneously focus on how student performance on those standards is measured.” Achieve is analyzing math and science standards and meeting with education officials in a number of Asian countries to determine how to compare them with academic expectations in the United States, according to Matthew Gandal, the group’s executive vice president.

Despite stark warnings in A Nation at Risk that foreign countries’ educational prowess threatened the global standing of the United States, the authors of the 1983 report were hamstrung by a dearth of comparable international data to support their case, says Gary W. Phillips, a chief scientist at the Washington-based American Institutes for Research.

“Policymakers need information to guide their work. A Nation at Risk didn’t have that,” said Mr. Phillips, who joined the U.S. Department of Education in 1986 and worked on national and international assessments for its research arm.

The report prompted demands for better state and national data, as well as more reliable international comparisons of student performance, he said. For years, the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, or IEA, had been the primary source for such comparisons. But officials in the United States and other countries were seeking more consistent and comprehensive student-achievement information than the original IEA tests could provide,Mr. Phillips said.

Following the release of A Nation at Risk, U.S. education officials were heavily involved in creating the Third International Mathematics and Science Study, or TIMSS, which he said greatly improved upon previous international efforts and is still overseen by the IEA.

Last year, Mr. Phillips published a study that ranked the performance of individual states on an international scale by linking their scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress to the TIMSS results.

The study highlighted the continued vast differences in states’ performance. Massachusetts 8th graders, for instance, ranked behind only four jurisdictions in math: Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan. By contrast, Mississippi 8th graders ranked behind 23 foreign jurisdictions, including not only the traditional top performers, but also such nations as Malaysia, New Zealand, and Slovenia.

In the post-Nation at Risk era, Mr. Phillips contends, states that ignore global trends face a “Lake Wobegon problem” of “seeing yourself only against the other people in the neighborhood.”

So far, no state has agreed to participate in a state-level sample for the Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA, which they would need to do prior to the August deadline. Sixteen states have taken part in the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study since it began in 1995, but only Massachusetts and Minnesota were state-level participants in 2007.

There is disagreement, though, over the prudence of such an approach.

“We’ve been going crazy with these anxieties since Sputnik 50 years ago,” said Iris Rotberg, the co-director of the Center for Curriculum, Standards, and Technology at George Washington University in the nation’s capital. She referred to the Soviet Union’s launch of an orbiting satellite in 1957, which touched off a drive by U.S. leaders to bolster education in scientific and technical fields.

Changes on the global stage have little to do with the math scores of U.S. students, said Ms. Rotberg, the editor of Balancing Change and Tradition in Global Education Reform. “The idea that this complexity and uncertainty would be less if U.S. students answered a few more questions correctly on international comparisons is absurd.”

She cautioned that international benchmarking will not solve the problem of inadequate student achievement, which is often tied to poverty and other social issues.

Nonetheless, interest in international comparisons has grown dramatically over the past two decades—and not just in the United States, said Andreas Schleicher, the head of education indicators for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, based in Paris. Some countries already use PISA to yield the equivalent of state-level results.

When he first joined the OECD a dozen years ago, Mr. Schleicher recalled, barely any “global dialogue” took place about education, and those discussions had “zero impact on policy.”

But in the mid-1990s, the OECD began planning for what is now PISA, a prominent international exam. It first reported nation-by-nation results in 2000, with more test scores in 2003 and 2006.

A study linked grade 8 scores on the 2003 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study with achievement levels on the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

SOURCE: American Institutes for Research

Today, education is typically the first agenda item at OECD meetings, Mr. Schleicher said.

“Nations have understood that it’s no longer good enough to be better than last year—you have to be globally competitive,” he argued. “That’s a new phenomenon.”

Indeed, Japan adopted a new curriculum in 2002 to make lessons more creative in response to perceptions that American inventiveness has helped the United States to thrive. Germany has sent teams of observers to Finland in recent years to learn why that country did so much better on PISA.

And governors and state education leaders from Massachusetts to North Carolina are increasingly looking abroad, said Mr. Linn of the governors’ association.

A group of elected officials, educators, and nonprofit leaders in North Carolina has taken study trips to more than half a dozen countries over the last several years, including Singapore, Great Britain, the Netherlands, China, and India.

Though the verdict is out on whether Ohio will translate the report’s recommendations into state policy, Mr. Chester said, its call for higher demands resonated deeply with policymakers and the public.

“Ohio has felt this as acutely as anybody,” he said. “Whether it’s in the steel, rubber, or auto industry, there’s growing agreement [on] this.”