A growing number of states and school districts are promoting bilingualism by offering special recognition for high school graduates who demonstrate fluency in languages other than English.

Thirteen states now offer a “seal of biliteracy,” and at least 10 more are working toward implementing a similar award. Students in nine of the nation’s 10 largest school systems can earn statewide or district-level recognition with the seal affixed to their diplomas or transcripts as official proof that they can speak, read, and write in more than one language.

Shifting demographics and political dynamics have transformed views on multilingual education in many parts of the country, paving the way for a focused examination of educating the nation’s 5 million K-12 English-learners and the importance of foreign-language instruction.

“It’s a small thing really, a seal, a medallion. But it’s a much larger issue than the seal of recognition,” said Shelly Spiegel-Coleman, the executive director of Californians Together, a nonprofit group that advocates for English-language learners and is the main proponent of the biliteracy seal. “Before this, having another language was a problem. Now, we know that this is not a problem, it’s an asset.”

Spiegel-Coleman’s home state of California was the first to adopt a seal, as part of an effort to acknowledge students who learned English without losing their native language.

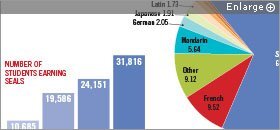

The nationwide growth and interest in the seal of biliteracy has mirrored the trends in California. The number of students earning the seal there has tripled since it was first offered in 2012, rising to nearly 32,000 for the class of 2015.

California’s statewide push was modeled after a 2002 effort in Glendale, Calif., a district where about a third of students are ELLs.

The school system has honored nearly 4,400 students with silver, gold, and platinum medals to recognize bilingual, trilingual, and quadrilingual students, respectively.

The district laid groundwork for the effort after the statewide passage of Proposition 227, a ballot measure that severely restricts the availability of bilingual education in favor of English-only immersion programs for ELLs. While not an outright ban on bilingual education, the measure almost eliminated it from public schools.

“We were still dealing with strong anti-bilingual sentiment,” said Kelly King, the assistant superintendent of the Glendale Unified district who oversees ELL services.

The tide has since turned. Come November 2016, California voters will have a chance to repeal Proposition 227.

Spiegel-Coleman said it’s telling that, through 2014, 40 percent of students who’ve earned the state’s seal of biliteracy were former ELLs. Californians Together leaders have even had preliminary discussions with leaders from several state colleges and universities about developing a similar initiative for postsecondary education, she said.

International Competition

Educators say that earning the seal of biliteracy could give students an advantage, opening the door for college scholarships, internships, and jobs that require proficiency in a language other than English.

“The business community has recognized the need,” said Elena Fajardo, an administrator in the California education department’s English-learner support division.

Beyond shedding a more positive light on bilingualism, proponents say the seal allows employers and colleges to distinguish between people who can get by in another language from those who are truly fluent.

Officials with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation say the growing interest in seals of biliteracy is promising if the United States wants to play a leading role in the global economy.

“We need to be thinking about the future now,” said Jaimie Francis, the senior manager of programs and operations for the foundation’s Center for Education and Workforce.

The organization’s state-by-state report card on K-12 educational effectiveness bemoans the lack of foreign-language proficiency among American students. The group places the blame on dwindling foreign-language-instruction options, especially in earlier grade levels.

“There’s opportunity and room for improvement here,” Francis said.

While many U.S. states require some world language credits for graduation, a Pew Research Center report found that most students in European countries begin compulsory foreign language instruction before the age of 10.

Since 2012, the state of California has offered a special designation or “seal” on the diplomas or transcripts of students who demonstrate that they can speak, read, and write in more than one language.

SOURCE: California Department of Education

With even more states considering adding the seal, four national professional organizations that represent language educators drafted recommendations for the seal of biliteracy. Among them: ELLs should demonstrate proficiency on state tests for English/language arts for all students and English-language development for English-learners; and native English speakers seeking to demonstrate proficiency in another language should achieve a state-determined minimum score on any number of tests, including Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate exams, and tribal-language assessments.

According to the organizations, it’s hard to track how many states have based seal requirements on their guidelines, especially since at least seven states already had approved seal programs. The implementation is just as challenging to track, as some states have turned it over to individual districts to implement, said Martha Abbott, the executive director of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

In California alone, more than 260 districts offer the seal of biliteracy.

“We don’t have data to determine whether the seal of biliteracy is something that people actually take seriously,” said Nelson Flores, an assistant professor in the educational linguistics division of the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education. “That’s going to depend on how it’s implemented in each of the states.”

‘Symbolic Gesture’?

Supporters say the seal of biliteracy has changed the conversation around multilingual education in unexpected places.

In Colorado, the Adams 14 district, which is under a compliance agreement with federal civil rights officials for systemic discrimination against bilingual teachers and ELLs, is one of three school systems piloting a seal of biliteracy option with hopes for statewide approval.

But the seal has proved most popular in the Western, Southwestern, and Northeastern United States, with many Southern and Plains states making little or no effort to adopt the recognition.

Flores fears the seals may overwhelmingly benefit affluent, high-achieving students while ignoring the needs of ELLs.

Most backers are from “self-selecting states that already support bilingual education,” he said.

To this point, the seals are “an important symbolic gesture,” Flores said. “It’s just the first step. We have to keep going and ask, ‘What are states doing to help students develop bilingual skills?’ ”

Staff members in Glendale Unified are taking those steps, pouring more resources into foreign-language instruction from the start.

A quarter of the district’s kindergartners are enrolled in dual-language immersion programs, and school officials have also looked to strengthen foreign education offerings in secondary schools. The programs teach the curricula for students in two languages to help them achieve bilingualism and biliteracy.

“You have to provide multiple pathways for students,” said King, the assistant superintendent who oversees English-learner services. “We opened the door for our district and community to embrace and institutionalize an expectation that our students become bilingual and biliterate.”