Corrected: An earlier version of this story used an incorrect pronoun for A. Brooks Bowden. She is an assistant education professor at North Carolina State University.

What’s more important to a superintendent: a math program shown to give a bigger boost to students’ math skills in the next two years or one that gives a smaller improvement but fits the district’s budget for five years?

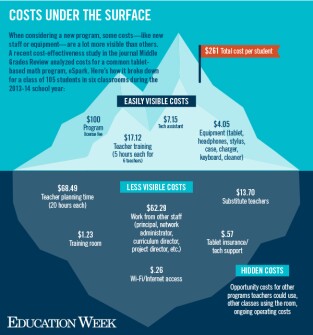

Questions like that have become steadily more common as school leaders grapple with years of shrinking budgets. Still, it can be difficult to understand the expenses that lie beneath an intervention’s sticker price or the resources that may mean the difference between a promising intervention working on paper and working in the classroom.

That’s why foundations, policymakers, and even the U.S. Department of Education’s research agency are pushing for more tools and research to help educators understand the costs of education programs.

“It’s a sea change that we have people saying we need to be cost-effective, not just effective,” said Lori Taylor, an education researcher with Texas A&M University. Taylor studies cost for the Texas Smart Schools Initiative, which provides tools for school leaders and parents to analyze academic returns to different spending approaches.

“In earlier research, it was seen as kind of sufficient to know that this intervention was working, without really digging down into the numbers to ask, ‘Well yeah, but ... how expensive is it and is it going to work better than the other things that also work?’ ” Taylor said.

‘Putting the Field on Notice’

Beginning this grant cycle, the federal Institute of Education Sciences formally required all future evaluation studies to analyze the costs to implement an intervention, including staff, training, equipment and materials, and other expenses, both at the start of and to maintain the programs over time.

Institute of Education Sciences Director Mark Schneider said he was “putting the field on notice"—half of the proposed intervention studies this year were disqualified because for lack of adequate cost analyses.

“As a field, we have been way, way behind the curve in terms of telling people how much things cost,” Schneider said. “We understand this is a challenge for the field, so we’re working on that.”

The rising interest in cost-effectiveness is partly due to economic necessity. More than half the states still provide less money for schools than they did before the 2008 recession, and in 19 states, local funding for schools fell at the same time, according to the latest analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. As schools across the country wrestle with years of belt tightening, leaders increasingly struggle to balance the effectiveness of research-based programs with the cost to put them into practice.

But researchers are also discovering that these bottom-line analyses, while being of more practical use to policymakers and practitioners, can begin to answer a question that has bedeviled researchers and educators alike for decades: Why does an intervention that shows great results with students in one district fall flat with a seemingly similar group of students elsewhere?

Accounting for Supports

For example, in an upcoming study, New York University doctoral researcher Jill Gandhi evaluated an inexpensive writing intervention designed to spur a positive academic mindset in low-income Chicago teenagers. Prior studies had found significant, lasting benefits for students who became motivated to learn “to make an impact on the world.” But in Chicago, the intervention had no effect or even hurt motivation.

Why? Gandhi suggested the problem may lie not in the cost of the intervention but the lack of subsequent supports, such as access to challenging classes or college planning. “Activating students’ motivation for learning and growth mindset with no other support might make students frustrated,” she said at a recent discussion of the research.

That’s not uncommon, said A. Brooks Bowden, a cost-effectiveness researcher and assistant education professor at North Carolina State University.

“We often say, here’s the cost to buy a textbook, and here’s the cost to use a new curriculum, without really considering the contrast between that curriculum and what was in place previously, or any other changes and services used to produce [effects on student achievement],” she said. And if one program helps students, it may also change the mix of supports those students need in the future.

“If we understand the resources needed in the programs we are delivering, someone in another state or district has a road map of what they need and what to do ... rather than just a budget figure,” she said.

Proposed new research priorities for the Institute of Education Sciences call for more studies of cost in education research. But different kinds of cost-related measures can provide different information for education leaders and policymakers, such as:

- Cost ‘Ingredients': These include all resources needed for an intervention, including teachers, volunteers, class space, materials and other items. Regardless of how they’re paid for, they must be known to recreate a program elsewhere.

- Cost-Effectiveness:

This kind of study compares the total cost of resources needed to get a particular result—such as improving the math skills of 3rd graders—to the total cost of other approaches that get equal results. This might be used, for example, by a superintendent trying to decide whether the district should invest in a new math curriculum or instead pay for a new teacher-training program for the existing curriculum.

- Cost-Benefit: This kind of study compares costs of implementing a program to the return on the educational investment over time; it requires more data and analysis than a cost-effectiveness study and often looks at longer-term effects. This might be used by a policymaker trying to decide whether the cost of early-childhood education will be returned to society in higher adult taxable income or lower incarceration costs for the children who participated.

Many programs already have administrative data on the different materials and training needed to implement a particular program, but researchers need to include that information from the start to get an accurate picture of the costs of a program. For example, one district may be able to use parent volunteers as reading tutors, and so may not calculate the cost of hiring and training tutors—but those expenses have to be included for a principal in a school with fewer volunteers to decide whether she can use the program.

That can be complicated, and it is one reason many education researchers have been slow to include cost in their evaluations or implementation studies of interventions.

“Anybody who does policy research understands that cost is important to policymakers. You can’t leave it out of the equation,” said Larry Hedges, an education professor at Northwestern University. Yet, he added, there has been “very little human capital in the education research world to assess costs in a meaningful way. ... If you asked people, should we be worrying about costs, the answer would have been yes, but when you ask them, ‘Well, how are you going to do that?,’ they have thrown their hands up very rapidly,” Hedges said.

The Center for Benefit-Cost Studies in Education, at Teachers College, Columbia University, looked at intervention studies supported by IES. In 2014, only two of 18 research evaluations planned to analyze the costs of their interventions. Two years later, that was up to seven of 22 funded studies, but they included few details.

The Education Department’s research agency has trained more than 150 researchers in how to measure cost-benefits and cost-effectiveness in the past five years. But the field has been relatively slow to take up costs.

The benefit-cost studies center has been building an online tool and database of more than 700 prices of educational resources—including 70 teacher-salary levels pulled from federal and state data—to help researchers and school leaders estimate program costs.

“I think there have been misconceptions about the work that goes into identifying and quantifying resources,” Bowden said. “I’m not doing this work because I’m ... interested in finance. I want to understand how we can better serve our students, what’s working for them, how we make sure they’re getting the resources that are effective. And this is a critical piece of that.”