On a beautiful, sunny morning one year ago, a 14-year-old New York City boy witnessed one of the most traumatic events in U.S. history while walking to school. He saw the hijacked American Airlines Flight 11 jet crash directly into the north tower of the World Trade Center.

After a second airliner hit the other tower, he and his schoolmates weren’t sure what to expect next.

Eventually, school officials led an evacuation of the building. As the boy stepped outside, the dust and debris from the buildings’ collapse were everywhere.

Now, the teenager said, he tries not to think about the events of Sept. 11, 2001.

“Most of the students try to put it behind them,” said the boy, now 15 years old and starting his sophomore year at the 3,000-student Stuyvesant High School, only a few blocks from where the twin towers used to stand. “They try not to think about it.

|

A new school year opens at Stuyvesant High School in Lower Manhattan last week. Despite experts’ assurances, worries about the school’s air quality are among the reminders of Sept. 11, 2001. |

“I don’t deny that it happened,” he said of the terrorist attack. “I don’t deny that there are fanatics out there. I’m trying not to focus on it. I can say the majority of students think like that.”

Is the boy doing OK? Or does he need counseling? That’s a question educators and mental-health professionals have been asking about many New York City children in the aftermath of Sept. 11.

But how to go about answering that question is a tricky task. Some mental- health experts suggest that all students should be screened for potential symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Others, however, point out that having children relive traumatic events through questioning or other means can be counterproductive. Rather, they recommend letting children rely first on the structures people naturally use in times of grief, such as family and friends.

In fact, 19 mental-health professionals from across the country made that point in a letter to Monitor on Psychology, a journal of the American Psychological Association, shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks. They were wary of therapists “descending on disaster scenes with well-intentioned but misguided efforts.”

|

Betsy Combier’s 17-year-old daughter, Sari, is a senior at Stuyvesant High School in Lower Manhattan. Last Sept. 11, Sari witnessed the collapse of the World Trade Center towers from a school window. |

Still, many children put on a positive front while “suffering quietly,” said Dr. Claude M. Chemtob, a psychiatrist who specializes in treating victims of trauma and also serves as a senior consultant for the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services. The board is one of several organizations providing mental-health services to students in New York City schools.

The differing responses and the ways students may mask them, most experts say, put teachers, principals, and school psychologists on the front lines to ensure that students are screened for psychological disorders, that they receive professional help if needed, and that they begin to heal from events that otherwise could leave lifelong scars.

In New York City, the Sept. 11 hijackers’ prime target, schools received high marks for their initial response to the terrorism. But now, many parents, psychologists, and children’s advocates are wondering whether the schools are prepared to deal with the emotional burden many students still carry.

“There are continuing concerns that parents have that children who need help are not getting it,” said Gail B. Nayowith, the executive director of the Citizens’ Committee for the Children of New York, a nonprofit research and advocacy group based in the city.

Emotional Toll

In a survey of more than 8,000 New York City children conducted last spring, about one in four reported symptoms related to the events of Sept. 11, and separate plane crash that occurred in the city soon thereafter, that suggested they would benefit from mental-health intervention.

About 8 percent of the 4th through 12th graders surveyed were deemed to have suffered “major depression,” 10 percent showed signs of “generalized anxiety,” and 15 percent had agoraphobia—the fear of being in public places.

More than 10 percent reported several symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder. The numbers were higher for youngsters who attended schools near the site of the World Trade Center.

At least a third of the children with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder were not receiving mental-health services, according to the survey, which was conducted for the New York City board of education.

“I was blown away by these figures,” said Michael Cohen, a principal investigator for Applied Research and Consulting, the New York firm that conducted the survey of 8,266 students. Mr. Cohen, a psychologist, helped coordinate the mental-health services in the city’s schools in the immediate aftermath of the attacks.

Many people, including local parents, said the schools did an admirable job in helping the city’s children in the period soon after the attacks. A June survey conducted by Ms. Nayowith’s group found that 79 percent of parents said the schools had done an “excellent” or “good” job in helping children last fall.

Schools provided small-group settings in which students could talk about the terrorist assault; teachers referred students to school counselors; and administrators provided information on where they could seek professional help. Nonprofit organizations such as Dr. Chemtob’s, along with the New York University Child Study Center and various hospitals, also sent counselors into schools.

But the city schools did not provide one service that psychologists generally believe all schools should supply in the aftermath of a traumatic event: basic psychological screening.

“When we don’t screen, we may miss kids,” said Robin H. Gurwitch, an associate professor in the department of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City. “As adults, we are not good at being able to identify all children in need.”

Ms. Gurwitch counseled children affected by the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. There was, however, no universal psychological screening of children in Oklahoma City in the aftermath of that deadly event because of some school officials’ fear of further traumatizing children.

But Ms. Gurwitch argues that one of the lessons learned is that educators and parents need to be taught about the benefits and importance of such screening.

And schools are the natural place to provide the service, psychologists say. Teachers and other school employees typically have established relationships with children, and the administration has an infrastructure to collect and analyze the results.

A spokesman for the New York City board of education said the district had decided to concentrate on providing services instead of screening children.

In addition, Ms. Nayowith of the Citizens’ Committee for the Children of New York said, questions about children’s privacy and parental consent had contributed to school officials’ decision to reject calls for screening all students.

Meanwhile, she argued, the schools haven’t done enough to give parents the information they need about the availability of psychological screenings that could be provided through federal disaster aid or private money dedicated to helping New Yorkers recover.

“There’s no doubt that there should have been screening made available to parents if they felt their child needed it,” Ms. Nayowith contended. “There could have been another way to reach out to parents and let them know screenings are available.”

Weathering the Trauma

Still, many people emphasize that children in New York have handled the trauma exceptionally well, considering its magnitude and aftereffects.

“What I find interesting is the amazing amount of strength that I’ve seen,” said Betsy Combier, the mother of four girls, ages 9 to 17, who attend New York City public schools. “They’re very, very together about the fact that a very, very bad tragedy happened to a lot of people.”

But Dr. Chemtob of the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services said that while many students are handling the situation well, others aren’t.

That’s why he also emphasizes the importance of screening, especially for teenagers, who are adept at masking their emotions. Teachers and administrators usually miss signs that not everything is OK for a child, even though the child insists he’s fine, said Dr. Chemtob.

At school, he said, students return to their routines, and that helps them feel as if their lives are back to normal. For many young people, though, the routine can give them a false sense that their emotional troubles are behind them, Dr. Chemtob said.

Most teenagers, he said, will respond to the question “How are you doing?” by saying, “I’m fine.” Well- meaning adults without a sense of how to probe for warning signs often take that at face value, he said.

With probing, he said, students might admit to having symptoms that suggest they are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Yet even after such admissions, it’s hard to persuade teenagers to seek professional mental-health services, he and others concede.

“There’s a very negative stigma attached to it, which we have to change,” Ms. Gurwitch said.

Nevertheless, psychologists say, schools—with their access to students and the resources to provide such help—could make a significant difference for young people who still feel the emotional stress associated with Sept. 11.

“We know that some percentage of children continue to have significant symptoms several years out [after a tragic event] unless you identify and treat them,” Dr. Chemtob said.

Anniversary Tensions

As the city—and the nation—prepared for the first anniversary of the attacks, New York school officials were approaching this week cautiously.

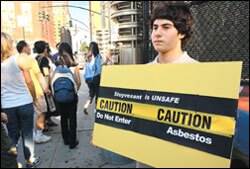

In a reminder of the lingering anxieties, students and parents stood outside Stuyvesant High School on the first day of school last week to protest what they said was the presence of asbestos and other environmental toxins from the Ground Zero cleanup. They believe those toxins may still be lingering in the school’s air ducts and carpeting.

But consultants hired by the Stuyvesant Parents Association and the United Federation of Teachers, the union representing city teachers, have assured students and parents that the city’s cleanup has been done properly, and that the building is safe, the leaders of the parents’ group said in a Sept. 2 letter to its members.

Parents have been complaining, though, about the air quality in the building since the school reopened last October. The tensions have been running high ever since, according to Judith E. Moore, a co- president of the Stuyvesant Parents Association.

“Worrying about what’s in that building can be a substitute for what’s happening in the world,” suggested Ms. Moore, a psychotherapist in private practice.

School leaders planned to have extra mental-health services available for children this week, and the board of education prepared a series of resources to help parents understand the emotions that students might feel during the anniversary. The resources also offer guidelines for how principals and teachers can appropriately mark the occasion.