By 1 p.m. Monday, as Hurricane Irma’s ferocity weakened and the storm continued its northward march, just 50 people were left at the shelter inside Boca Raton High School.

It was a dramatic change from just a day earlier, when 1,700 evacuees had sought shelter at the high school in the Palm Beach County school district, about 50 miles north of Miami.

One of the holdouts was Susie King, the principal, who’d been hunkered down at the school since dawn Friday. With 32 volunteers working in the shelter—many of them school employees working around the clock to feed evacuees, keep the shelter clean, and provide other supports—King had pivoted to deploying her skills as a decisionmaker, problem-solver, and comforter, which she usually devotes to the school’s 3,500 students and their teachers.

Similar scenes had been playing out in other Palm Beach County schools—where during the storm’s peak 17,000 evacuees sought refuge, according to Superintendent Robert Avossa—and across the state’s emergency shelters for multiple days as Hurricane Irma churned toward Florida and millions of people sought a safe place to go. The size and predicted ferocity of the hurricane prompted the evacuation of more than 6 million people, tens of thousands of whom either had no means to leave the state or waited too long to find other options for escaping the storm’s direct path.

About 600 shelters had opened across the state ahead of the storm’s arrival, and about 500 of those were housed in K-12 schools.

By late Monday afternoon, roughly 162,000 people were still in shelters across the state, according to the Florida Division of Emergency Management. And some school-based shelters were beginning to move toward closing down, said Meghan Collins, a spokeswoman for the Florida department of education.

At the same time, Collins said, state and local officials were hashing out which shelters needed to stay open to house evacuees who find their homes uninhabitable. In Palm Beach County, where 14 schools had been shelters, the district had closed all but one by late Monday, Avossa, the superintendent, said.

Many of Florida’s counties have agreements with school districts—which are also countywide—saying that school buildings can be used as evacuation shelters during hurricanes, said Jodie Halsne, the manager of mass care and sheltering for the American Red Cross. Schools are frequently used as shelters because they are plentiful, officials know how many people the buildings can hold, and they are solidly built structures, she said.

All-Hands Effort

Bringing order to chaotic situations is familiar territory for many educators, helpful experience for working in shelters where people can be under a great deal of stress and strain.

“It comes naturally to school personnel,” said Andrea Messina, the executive director of the Florida School Boards Association. “They just show up and say, ‘Tell me what to do.’” For principals and assistant principals especially, who know their facilities intimately and are used to being in charge, they “are not afraid to make a decision,” Messina said.

At Sessums Elementary School in Riverview, Fla., Principal Allison Norgard had been on duty nearly nonstop since Friday when the school became refuge to more than 1,600 people.

The school’s head custodian and main secretary never left the building until the storm had moved through early Monday, she said. A custodian from a neighboring school also joined them for 48 hours to help maintain order and cleanliness in the Hillsborough County school.

Between Norgard, three Red Cross workers, a county sheriff deputy, and numerous other school staff and community volunteers, Sessums’ shelter team ran a tight ship on meal service and keeping people in the right rooms for their needs. One part of the building was reserved for families with young children. Elderly evacuees were kept on the ground floor, and another space was reserved for people with older or no children.

Norgard’s job was to take care of the details—no matter how prosaic. Wiping tables and making coffee were among the duties she took on, along with dispensing hugs to children and tending to various needs of evacuees.

“I know that if the people truly know that we care about them and their safety, then I believe that it would be a better experience for everyone,” she said.

As evacuees began leaving Sessums earlier Monday, Norgard said they asked for brooms and cleaning supplies. They wanted to help clean the school.

“I cried today when I walked through my building,” she said. “Because the people were so respectful. It was clean. The bathrooms were clean. We didn’t expect that.”

Transitioning Back to School Mode

For many districts across the state, reopening dates were still up in the air as officials were just beginning to get a grasp of how much damage Irma had brought to their buildings. Getting a handle on the availability of teachers, many of whom would have evacuated, as well as when students would be returning to their homes, will be another logistical challenge in making decisions about reopening.

And for districts where dozens of schools had been operated as shelters, there’s different work to be done to ready them for reopening. Messina, of the school boards association, said cots must be broken down, floors must be sanitized to required standards. If shelters allowed pets, dander must be removed, she said, while shelters that took in elderly evacuees might need more time to help them transition back into their homes or assisted living facilities.

“The people running the shelters are being diligent,” Messina said. “They are trying to assist evacuees first and then get back to schools.”

Guarn Sims breathed a sigh of relief Monday afternoon, after the last of his 1,200 shelter guests left Boynton Beach Community High School, the Palm Beach County school where he’s the principal. People started flowing into the center Friday afternoon, and by 10 a.m. Monday, he received the “all-clear” that everyone could leave.

It was “humbling,” he said, to see people from all walks of life being kind and helpful to one another in stressful conditions. The building’s power went out late Sunday afternoon on Sunday, and the generator kicked in, but that didn’t support air conditioning. Temperatures soared inside the school, Sims said. Still, people were grateful for the food and shelter they received there, Sims reported.

“They overlooked how hot it got last night, and they were still appreciative we brought food to them,” he said.

Now, Sims said, the hard work of restoring the school in time for the return of students will get underway, with picking up trash and cleaning bathrooms at the top of the to-do list, he said. The school wasn’t damaged by Irma.

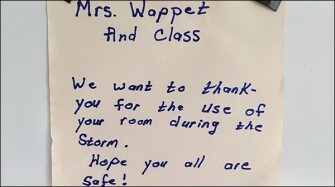

As teachers at Sessums Elementary in Riverview packed up ahead of the storm last week, they wrote notes on their classroom white boards to welcome evacuees and point them to puzzles, pens and paper, and bottles of hand sanitizer they had left for them.

Some evacuees responded in kind before they cleared out of the school Monday.

“Mrs. Wappet and class,” one person wrote, “We want to thank you for the use of your room during the storm. Hope you all are safe!”