Private management of public schools has traveled a rocky road since the school choice movement took hold in the early 1990s. With entrepreneurial zeal, education management organizations, or EMOs—for-profit companies that can open and operate charter schools as well as manage regular public schools—promised to provide high-quality education in a more cost-effective and innovative way.

So have EMOs delivered?

That depends on whom you ask.

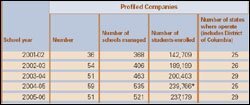

In the past decade, millions of investment dollars have been spent, EMOs have closed schools or lost contracts to run them, and some companies have gone belly up or merged with competitors. In 2005-06, the number of EMOs dropped 13 percent compared with 2004, from 59 to 51 companies, according to a report published in May by Arizona State University’s Education Policy Studies Laboratory.

Analysts at Boston-based Eduventures forecast strong revenue growth in the market for outsourced administration services in K-12 education.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: Eduventures LLC

Clearly, some companies are finding their way, having diversified their business models and strengthened school leadership, community relations, or other fundamentals. Several companies, such as Grand Rapids, Mich.-based National Heritage Academies and Akron, Ohio-based White Hat Management Inc., are even thriving, opening more schools in more states and claiming profits.

Still, the verdict on the education management industry is decidedly mixed. Some industry experts say the EMO model has failed—that it is too politically divisive and labor-intensive, as well as poorly suited to harness the economies of scale.

“Despite the free-market rhetoric, the for-profit EMO industry by itself isn’t viable,” said Alex Molnar, the director of ASU’s policy-studies lab and a critic of privatizing public education. “Without [federal funding], the industry would be flat on its back. It would be a smoking suit.”

Others counter that the still-young EMO market is experiencing growing pains, and that despite strict regulations and intense political pressures, among other obstacles, EMOs are resilient and improving their business models.

“Many companies have discovered that this is harder than they thought,” said Steven F. Wilson, a senior fellow at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and the author of Learning on the Job: When Business Takes on Public Schools. “But there are some early and positive results, and the story is far, far from over.”

‘Their Time Has Passed’

In the 1990s, some legislative and business leaders spoke fervently about how the private sector could manage public schools better than government. They blasted what they saw as Byzantine school district bureaucracies for spending too little on students and too much on central administration.

Such criticisms provided a fertile ground for education management organizations to take root, the most prominent of which was New York City-based Edison Schools Inc. Venture-capital firms envisioned high returns and invested millions of dollars.

Consequently, many EMOs pursued aggressive growth strategies, opening schools at a rapid pace. In time, they found that pace was not sustainable.

Researchers who track for-profit U.S. education management organizations say the sector is shrinking by some measures.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: Education Policy Studies Laboratory, Arizona State University

Many EMOs entered the fray knowing little about the economics or politics of education, says Henry M. Levin, the director of the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education, based at Teachers College, Columbia University. He and other observers say that EMOs vastly underestimated the time, energy, and money needed to open and operate charter and other public schools.

“The idea was that you could go in, make money, get a better academic outcome, and also that there would be a lot of support for these kinds of [privatized education] models once they demonstrated results,” Mr. Levin said. “None of that has occurred.”

Among the reasons why, analysts say, is that EMOs have high marketing costs and often only one educational model to offer.

Some also say states’ charter school laws put EMOs at a disadvantage: Typically, EMOs cannot actually hold charters, so they are not ultimately in control. So EMOs act merely as advisers, although they shoulder all the financial risk, some analysts say.

In addition, the rise of the school choice movement coincided with that of the accountability movement, and EMOs with schools across states found they had to realign their curricula to match each state’s standardized tests. That, experts say, was a labor-intensive task.

“EMOs are not the bleeding edge of the industry anymore,” maintained Marc Dean Millot, the editor of School Improvement Industry Weekly, an online newsletter that favors market forces in education. “Their time has truly passed.”

Yet other observers of the field say that EMOs will not only stick around, but will be a genuine force in public education in coming years.

Eduventures, a Boston-based market-research firm that tracks the K-16 education market, predicts that the market for both EMOs and nonprofit charter-management organizations, or CMOs, will grow 14 percent in the 2006-07 school year, to $2.3 billion in revenues. The firm estimates that revenues will grow another 12 percent by 2008-09.

The firm notes that the federal No Child Left Behind Act allows EMOs and CMOs to provide students in schools that fail to reach student-achievement targets under the law with supplemental education services. Moreover, Eduventures analysts expect school districts to turn increasingly to EMOs to run schools that are required to restructure under the federal law.

‘Alive and Working’

In addition, consumer demand for charter and other alternatives to traditional public schools will continue to grow, creating an environment more receptive to for-profit education, argues Michael R. Sandler, the founder of Eduventures and the chairman of the leadership board of the Washington-based Education Industry Association.

While the story of the EMO industry has not been a huge success, he said, “it’s alive and it’s working.”

Mr. Wilson of Harvard agrees. “The industry is evolving,” he said, “and the players are learning on their feet.”

Take Charter Schools USA Inc. The company, which has 27 charter schools in Florida, at one time also operated several schools in Texas that the company no longer runs. Jonathan K. Hage, the chairman and chief executive officer, said the Fort Lauderdale, Fla.-based company stumbled in the Lone Star State mainly because of a “political and legislative environment” that was less friendly to charters than that in Florida.

“That definitely was for us a learning curve,” he said. “We’ve learned that our focus is on schools that are more local, or within a much more attainable distance, to be able to support them.”

Edison, the most ambitious and high-profile of the EMOs, has also learned the hard way. The company scaled up too quickly, burning through $500 million before posting its first profitable quarter in 2003. Edison opened its first four schools in 1995 and by 1999, it operated 79 schools and 38,000 students nationwide.

The company found it hard to handle the logistical, political, financial, and academic problems that came with opening and managing schools at such a fast rate. Complaints rose. Bills were paid late. Teacher turnover was high.

Forward momentum further slowed in 2001 when a $50 million, five-year contract with the Philadelphia school district to manage 45 schools and the district office triggered political turmoil. After the dust settled, Edison ended up managing 20 schools in the city.

Edison now manages 101 schools in 19 states, serving 61,000 students. Over the past several years, it has also diversified, providing 250,000 students after-school tutoring, summer school, and benchmark-assessment services. The company also serves 20,000 students in the United Kingdom.

Christopher Whittle, Edison’s chief executive officer, is sanguine about the company, despite its tumultuous past.

“There are always challenges and unexpected turns and twists along the way that inform how an industry develops. And industry pioneers pave the way for others as they learn what works well—and what doesn’t,” Mr. Whittle said in an e-mail. “That just comes with the territory.”