The commercial begins with a cheery “Hi, y’all!” from the country-pop trio Dixie Chicks, followed by flashes of concert footage mixed with black-and-white interview scenes. Between giggles and hair tossing, the musicians reflect on the challenges of fitting in during their high school days.

|

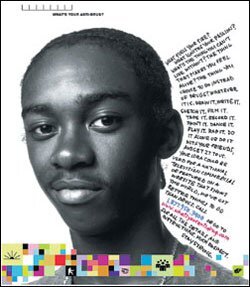

The image above is one of many employed by the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign to persuade young people not to use drugs. |

“There are pressures at every angle to take drugs,” says the group’s lead singer. “I really feel having the creative outlet is the only thing that really pulls you out of that and makes you make the right decision.”

Part of the federal government’s 4-year-old National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign aimed at curbing youth drug use, the 30-second ad spot is as eye-catching cool as an MTV video. But if the goal is to convince young people to just say no, it’s apparently not working.

A new study for the federal government, based on interviews with 8,200 9- to 18-year-olds and 5,600 of their parents from September 1999 to last December, shows that while the campaign advertisements aimed at parents are having small positive effects, those targeted at the youths themselves are falling flat.

“The evidence is at least somewhat consistent with the campaign being effective with parents—in encouraging them to talk to their kids about drugs and know where [their children are] and who they’re with,” said Robert C. Hornik, a lead author of the report and a professor of communication and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication.

“We don’t see these findings with youth,” Mr. Hornik said. “Those trend lines are going in the wrong direction.”

In fact, follow-up interviews with the first group of youngsters interviewed suggest greater exposure to the ads might actually help initiate drug use.

“Obviously, this is a very strange finding, and we’re tentative about it,” Mr. Hornik said, adding that researchers plan to reinterview the rest of the youngsters before offering any conclusions.

Drug Czar’s Reaction

President Bush’s drug czar, John P. Walters, doesn’t intend to wait for the data. Armed with the preliminary findings, which were not available to the public as of last week, the director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy hit the interview circuit last month, panning the media campaign.

“If we were doing a medical, clinical test of ... a new treatment and we had these kinds of findings, it certainly requires us to stop and change what we’re doing,” Mr. Walters said in a May 15 NBC interview.

Still, the White House wants another $180 million from Congress to continue the campaign. Mr. Walters said the ads can work if the campaign targets older teenagers with focus-group-tested messages more along the lines of a controversial series of spots that debuted during the Super Bowl, linking youth drug use with terrorism. (“Teen Drug Use and Terror Linked in Television Spots,” Feb. 13, 2002.)

“But if we in the administration don’t believe we can use this effectively, we will end it and [Congress] should end it,” Mr. Walters said.

Some involved with the campaign suggest that it’s been smothered by the government bureaucracy that oversees it. The only way to fix the program is to turn the creative process back over to the experts in the advertising business, argues Stephen J. Pasierb, the chief executive officer and president of the Partnership for a Drug-Free America, which manages the roughly 40 agencies that contribute pro bono advertisements to the campaign.

The main problem, Mr. Pasierb said, is the government’s flawed message strategy, purchased from a public relations company, and an 18-step creative-review process that takes almost 200 working days to get a 30-second spot on the air.

“We have to streamline the creative process and put the advertising professionals back in charge,” he said. “It’s just an ad campaign—it’s not the solution—but it’s very important because it reaches a lot of people, and I think a lot of people want to see it fixed.”

Because teenagers traditionally have been a tricky target group for advertisers, some experts in drug-abuse prevention cast doubt on whether the media campaign is the best use for the taxpayers’ money the White House wants from Congress.

“I would rather see Congress put the money into treatment programs designed specifically for teenagers—that’s where you would get the maximum impact,” said Mathea Falco, the president of Drug Strategies, a nonprofit research institution in Washington.