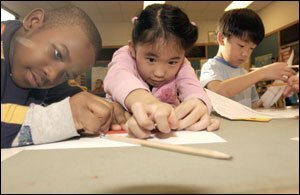

Joe DiCarlo has long suspected that Montessori schools’ multiage classrooms, student-selected schoolwork, and lack of formal tests or letter grades cultivate students’ academic and social skills better than traditional schools.

It’s a “community where students are going to cooperate and get along and experience the enjoyment of learning,” he says.

DiCarlo is hardly impartial—he’s been a Montessori teacher for more than 15 years. But a recent study published in the journal Science appears to prove that, at least in Milwaukee, the 4th to 6th grade teacher is right.

The report found that children at his public school, Craig Montessori Elementary, which typifies the Montessori learning format, had demonstrably superior social skills and performed as well as or better than their public-, private-, and charter-school peers on a standardized reading and math test.

The findings are significant because the research on Craig, which caters largely to minority children, was unusually well-controlled. Since the 59 Craig students studied were admitted to the school based on a lottery, their parents’ income levels—an important predictor of academic success—were in the same range as those of the control group: 53 children who lost the lottery and attended other local schools.

“Evaluating Montessori Education,” originally published in the journal Science is posted by The Opera Nazionale Montessori.

The study, “Evaluating Montessori Education,” assessed four sets of students, comparing 5-year-old and 12-year-old Montessori students with their peers at other schools. The younger Montessori children scored better than their coevals on seven scales of the Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery, a standardized test often used to identify children with learning disabilities. They were also more likely to participate in positive group play on the playground. The 12-year-old Montessori students wrote more creative essays with more complicated sentence structures than the other 12-year-olds and gave better answers to questions about social dilemmas. They also scored just as well as their non-Montessori peers on the Woodcock-Johnson test, despite being less accustomed to formal tests.

Angeline Lillard, a University of Virginia psychology professor and lead author of the study, says that schools’ reliance on standardized testing to improve student performance has its shortcomings. She notes that Montessori classes do feature frequent informal testing, such as a teacher quizzing a kindergartner on the color of her jacket, but says schools that teach to standardized tests may not allow students to pursue subjects they are interested in, and can stifle their love of learning.

“You get even more emphasis on extrinsic rewards and get away from learning as a value in its own sake,” she explains.

The longitudinal study is one of the most comprehensive yet on the relative merits of a Montessori education, according to Giselle Lundy-Ponce, a policy analyst for the American Federation of Teachers. But Lillard says more research is needed to discover why, for example, the older Montessori students failed to outscore their public-school counterparts, as the Montessori 5-year-olds did.

Indeed, it’s too early to single out Montessori as the paragon of early childhood education, Lundy-Ponce contends. For starters, she says, the study’s sample size is too small to draw definitive conclusions about the format. Moreover, she notes, the study didn’t factor in how much reading exposure the students had at home. Finally, although Craig was chosen for the study in part because it has a well-implemented program, not all Montessori schools adhere to the model system.

“Learning how to think for themselves, being better human beings,” says Lundy-Ponce, “is not everything children need to get ahead academically.”

Still, the study bolsters Montessori’s credibility, according to Phillip Dosmann, principal of Craig Montessori. He says Craig has lost students to other schools because parents wanted traditional grades, report cards, and homework as their children got older. “We get results using the Montessori curriculum,” says Dosmann. “That’s why this study is powerful.” —Eric Wills