| Fighting the flow of disease into and around this region can feel like bailing out a waterlogged boat with a sieve. |

The old wooden sign clanking in the wind off a two-lane highway here reads: “Pueblo Nuevo.” But nothing in the 100-acre expanse of scrub brush and corrugated metal looks remotely like a town or the least bit new.

To get to their classes in the morning, children in this colonia, or “neighborhood,” walk down garbage-strewn dirt roads, past dilapidated wooden shelters, outhouses, and trailer parks patrolled by skinny, growling dogs. A nauseating stench permeates the humid south Texas air as families cook food alongside trenches filled with waste water.

When it rains, the dirt roads are transformed into rivers of mud so impassable that school buses won’t venture into this colonia, one of more than a thousand unincorporated neighborhoods built without sewage or potable water that snake along the Texas-Mexican border from Laredo to Brownsville. After a storm, parents here wrap their children’s shoes with plastic or carry their offspring out to the buses so they won’t arrive at school muddy.

Occupied mostly by poor Mexican immigrants eager to buy cheap land, these shantytowns are in sharp contrast to the modest homes of middle class families just a few miles away. “It’s Third World living conditions right here in America,” says one local health worker. And the thousands of schoolchildren who live in this squalor have Third World health problems, too.

This spring, the schools and state and local health officials in Texas’ 32 border counites have instituted periodic mass- inoculation campaigns in the schools in an attempt to coax down the rates of disease. But they say fighting the flow of disease into and around this region sometimes feels like bailing out a waterlogged boat with a sieve. They are battling to improve children’s health when everything from the environment to political and financial forces seems to be aligned against them.

| Infection rates in many of the counties along the Mexican border are more than double the national average. |

Nationally, the United States has managed to reduce or eliminate many childhood infectious diseases through mass-immunization campaigns. Since the 1970s, the U.S. has spent billions of dollars and has quashed diphtheria, reduced tetanus, and eliminated native strains of the measles. Government health officials boast that every one of the 100 cases of measles reported in the United States in 1998 was imported by visitors from other countries. “There is now no indigenous strain,” says Larry Pickering, a pediatrician with the national immunization program, a part of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. But here, in these border towns, the next outbreak could be just around the corner.

Infection rates for Hepatitis A, chicken pox, dengue fever, and tuberculosis in many of the counties along the Mexican border are more than double the national average. The statistics were so alarming that the Texas department of health instituted a requirement last year that children in the border towns must be immunized against Hepatitis A, a virus that attacks the liver and can cause jaundice and nausea, before they enter school this fall."We’ve done a good job of getting kids immunized, but there are still some kids who are lagging behind,” Pickering says.

The townsalong the border are like one big petri dish, health officials say. Infections flourish mainly because of the transience of the population, the unsanitary, crowded living situations, poor hygiene habits, and tightly packed schools with overworked nurses.

It’s also because Mexico, where many infectious diseases are endemic, is right across the river.

Mariachi music blares out of a parked car in the central square of old downtown Laredo. The Spanish founded what are now Laredo, a city of 195,000 residents, and Nuevo Laredo, its Mexican cousin just across the Rio Grande, in 1755. They split into two cities in 1848.The two are tightly bound by culture and commerce. Thousands of trucks laden with goods cross the border in both directions every day. Residents on the Texas side travel south to shop and visit relatives. Sometimes, they bring back tuberculosis along with their souvenirs.

Disease also travels by water. The Rio Grande, ranked the seventh-dirtiest river in the country, has been polluted with industrial waste from Mexican factories for years. Linda Flores, the director of school health for the 26,000-student United Independent School District of Laredo, says that “many children absent for gastroenteritis get their drinking water from the river.”

Juanita Martinez, a teacher at Ruiz Elementary School here says one of her kindergartners swam across the Rio Grande with his parents recently. “Because they entered the country illegally, they didn’t get checked up,” says Martinez, noting that such newcomers may introduce illnesses to other children.

A U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1982 required, however, that schools accept children who are illegal aliens. Enrolling sick children “shouldn’t happen, but there’s nothing we can do,” Martinez says. Hygiene and sanitation throughout the region are poor. Many families lack even the most basic modern conveniences, such as a sink with running water to clean their food. In many homes, especially on the colonias, wash basins may be inches from the latrine.

‘It’s Third World living conditions right here in America.’ Local Health Worker |

Nearly 200 miles southeast of Laredo, in the town of Weslaco in Cameron County, Ramon Gonzales is inspecting a house on a colonia where a pipe is discharging waste water onto the grass. The puddles of gray water are a magnet for mosquitoes, which can carry diseases like dengue fever. “This is an environmental disaster waiting to happen,” says Gonzales, a director of border health for the Texas health department.

All the colonias along the Rio Grande came into being in the 1960s, when a deluge of Mexican immigrants purchased small lots from land developers. The lots had no sewage systems, drinkable water, roads, or regular trash pickup. Because the contracts for these properties were rarely written in Spanish, many buyers didn’t know about the properties’ shortcomings.

In 1994, the Texas legislature passed a law barring developers from selling property that lacked basic infrastructure. But it didn’t require that the existing 1,500 colonias be retrofitted.

The unhealthy living conditions on the colonias, as well as in the towns along the border, affect children’s ability to keep up in class and to focus on their school work, says Martinez, the Laredo kindergarten teacher. Many children come to school with fevers because they prefer her class to staying home, she says. “They love to come here because the amenities are better. But children cannot function in class if they are hungry or sick.”

Laredo students score below the state average on achievement tests. In 1999, 64 percent of students in the Laredo Independent School District, the other district in the Laredo area, passed the state assessment compared with 78 percent of students statewide.

“Schools, malls, and churches are the best place to catch disease,” says Linda Jo Perez, the health coordinator for the 23,000-student Laredo Independent district. On a hot spring afternoon, she is directing traffic at C.L. Milton Elementary School as a dozen school nurses and workers from the Texas health department stack vials of syringes and interview parents and children on what vaccines they need.

Advertising is key for a good turnout. For today’s immunization clinic, the health department and the school district distributed flyers, ran radio ads on several Spanish-language stations, and publicized the event through the schools for weeks.

|

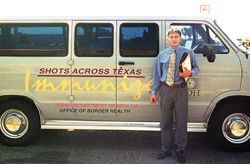

Ramiro Gonzales, a director of border health for the Texas health department, travels the region, promoting sanitary living conditions and environmental awareness. |

Like waiters listing the specials of the day, the nurses tick off an impressive menu of inoculations: Hepatitis A and B, measles, mumps, rubella, polio, tuberculosis, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, and chicken pox. The new state requirements mandate that children younger than 5 living in border communities get Hepatitis A shots by this fall. In 1997, the Hepatitis A rate for Webb County, which includes Laredo, was 105 per 100,000 people, more than quadruple the state rate of 23 per 100,000.

And by this fall, 6th graders must show proof that they’ve had the Hepatitis B vaccination within 30 days of their 12th birthday. The state also requires that children who will turn 12 before this August get vaccinated against chicken pox.

Since 1971, the state has required children to have the other shots—for measles, mumps, rubella, polio, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus—before entering a Texas classroom.

“This might sting,” says one of the nurses at at Milton Elementary as she pricks a freckled teenager with a needle to test for tuberculosis and then gives him a booster shot to protect against tetanus. “My arm’s asleep,” 13-year-old Josh Maldonado winces. “It feels like if you got a girl mad, and she pinched you real hard,” he says.

“They don’t know us as the ‘witches of immunization’ for nothing,” jokes Flores, as children’s cries reverberate around the cafeteria. “We are a parent’s nightmare.”

Such minor pain is necessary, however, says Perez. More than 30 per 100,000 people in Webb County has tested positive for TB—triple the Texas rate. Tuberculosis, a respiratory disease that can damage the lungs and can even be fatal if untreated, is as easy to catch as the flu. “One person in a crowded house’s got it, everyone does,” says Perez.

| The problem is so prevalent that officials require all schools to test potential employees for TB before they can be hired for any position in the district. |

The problem is so prevalent here that Webb County officials require all schools to test potential employees for TB before they can be hired for any position in the district. They also conduct annual screenings of all 30,000 district employees, from custodians to principals.

“It’s a hassle, but it’s worth it to do that,” says R. Jerry Barber, the superintendent of the United Independent School District of Laredo.

Perez and Flores have been here for outbreaks before, and they don’t want to see them repeated.

Laredo suffered a measles epidemic in 1990, when several dozen children were infected. Nurses had to inoculate 20,000 children over five months to contain the disease. In 1995, the county had a Hepatitis A outbreak, linked to street vendors in Nuevo Laredo.

But Laredo hasn’t had a serious contagion in several years. And it’s had some success recently. In 1998, the rate of chicken pox infection plummeted well below the state average.

A day after the immunization clinic in Laredo, school nurses and state health-department workers in Cameron County in the Rio Grande Valley are also sticking students with needles.

Here, 200 miles south of Webb county, the health statistics rattle the doctors. The rural county dotted by small towns has a hepatitis A rate of 67 per 100,000 residents—six times the national average and more than triple the state rate. Their TB rate is nearly quadruple the Texas rate, and one out of every 867 residents here came down with a case of chicken pox in 1998.

Because some vaccines, like the one for Hepatitis A, take several shots to be effective in preventing infection, children have to return again and again, an often difficult task.

One enticement is that the shots are cheap.

Vicki Mendoza, who is checking in parents and children from preschool to high school at an afternoon clinic at Greene Elementary School in La Feria, says school and health workers don’t refuse anybody. “There’s a lot of people that can’t afford even $5. So we give it to them,” she says.

Maria G. Gonzales, one of the parents in the line, is carting three children and wears a worried expression. As her oldest daughter, Irene, 16, sits for the required Hepatitis A vaccine, the diminutive 42-year- old mother whispers that she doesn’t have a dime in her purse.

“It helps to have free shots. It’s hard to afford food even,” she says. At a private clinic, shots can cost more than $100 for a full series for a family of four. “If they cost money, [my children] would not get them,” she says.

Gonzales’ disabled husband was recently sacked from his trucking job, and the family is desperately trying to raise the gas money so they can drive to Holland, Mich., where the family works the blueberry fields in the summer.

| School officials say the huge need and the limited number of health-care providers in the region are problems. |

Many of the migrant workers who live along the border—including about a sixth of the school enrollment in some districts—take their children east in the summer to work orange groves in Florida or north to Idaho potato fields. “Because these families migrate during the harvest time, it’s harder to get them regularly scheduled doses,” and that can drive up the infection rate, says Laurie Henefey,a state health-department immunization-program manager for several border communities.

The Gonzales children are always coming down with something, but after Irene gets her shot, all of Maria Gonzales’ children are up to date on their vaccinations for the year, the mother says.

School officials in La Feria say the huge need and the limited number of health-care providers in the region are problems. Health experts say the threats are aggravated by the population boom. The population of border communities has tripled in the past 25 years—a result of high birth rates and continuing immigration.The rapid growth is expected to continue. In Laredo alone, the schools enroll about 1,400 new students every year. It’s one of the fast-growing districts in Texas.

No one knows this trend better than Dr. Stan I. Fisch, a pediatrician who has lived in the border region since 1973. He and his five associates serve 27,000 families in Cameron County. As families here average three children each, that adds up to about 80,000 children.

With a shortage of pediatricians in the area—only about 15 in Harlingen—the biggest town in Cameron County—there are plenty of earache, asthma, and gastroenteritis cases to go around.

“They aren’t all coming in at the same time, thank God,” laughs the good-natured Fisch in his toy-strewn entryway. But he says soberly, “we do see 100 to 200 patients a day.”

| Better health, and as a result, better school attendance, is the key to ending the cycle of poverty here. |

The most common illnesses they treat are diarrhea, intestinal parasites, and TB—illnesses that arise chiefly, he says, from living in unsanitary environments. A young boy he treated this year, for example, who lives in a trailer with four other people, missed 26 days of school because of a stomach ache.

Fisch sees better health, and as a result, better school attendance, as a key to ending the cycle of poverty here. “The best chance would be if children would do well in school, and they can move out of here,” he says. “If they don’t, you’ll have another generation suffering the same problems.”

In general, Fisch says, he and other physicians are frustrated in their efforts to educate parents about their children’s health needs. “We put a Band-Aid on, and they go home, and the Band-Aid peels off the next day,” he says.

Beverly Klebert, a 70-year-old school nurse for the La Feria school district, says another problem is that many patients independently try to treat themselves and their children by purchasing medicine that is sold over the counter in Mexico.

“They go to Mexico to get antibiotics for whatever problem. They throw the pill down their throat, and they feel better,” Klebert says. “It’s easy to think antibiotics is a cure-all. But if it’s a virus, it’s not going to cure that.”

When it comes to exploding myths about health and medicine and environmental problems, promotoras, or promoters, make sure the message gets home. Up and down the Rio Grande, Texas A&M University employs women who live and are respected in the colonias to educate their neighbors about how to improve their health.

Originated by Mexican health workers, the practice has been extremely successful here where recent immigrants—many of them illegal—are reluctant to ask for advice from any public official for fear of being deported.

In Brownsville, at the southern tip of Texas, three promotoras in bright blue vests walk into a dirt yard where a 4-year-old girl is playing in her life-sized wooden dollhouse.

The neatly painted blue and white playhouse is in contrast to the rusted beige trailer that the family of three occupies on this tiny lot. This colonia, called “Cameron Park” by its residents, is an odd polyglot of structures. Down the dirt road, a wood house with a periwinkle trim sits next to a burning heap of trash. People can’t afford trash pick up so they often torch it, sending noxious fumes into the windless air.In Spanish, the ladies ask the girl’s mother a series of questions: Where do you go if you feel sick? What diseases have you or your family had? Has your daughter had all her shots?

They test her knowledge of nutrition and ask her about environmental hazards here. The 27-year-old mother says the drinking water is a problem and so is drainage. “The water has chemicals in it, and sometimes comes out dark,” she says.

Teresa Serna, one of the promotoras, says that after they survey the residents here, they will start their education campaign. At the end, they will conduct a follow-up survey to gauge how much the residents have learned. “I see a lot of need in this community,” says Serna, who has lived here since 1972.

Despite their efforts to improve the health in these communities, schools sometimes are their own worst enemies, says Klebert, the La Feria school nurse.

‘The best chance would be if the children do well in school, and they can move out of here. If they don’t, you’ll have another generation suffering the same problems.’ Dr. Stan I. Fisch, |

She says many parents get the message from these poor schools that students must attend class—even when they’re sick—so that the district doesn’t lose money from the state. Schools’ state aid is based partly on attendance figures. Parents also have a strong sense that education is the way for their children to earn a better living. As a result, the attendance rate in the border region is 95 percent."Austin [the state capital] pays for kids who are in school, so the principal triesto keep them in,” Klebert says. “If [the principal] ever had an epidemic, it would scare the pants off ‘em.”

Flores, the Laredo school nurse, says that children occasionally are allowed to sneak into school without getting shots because school administrators interpret a loophole in state law to mean they can be in school for 30 days before they have to have their shots. The law actually says their medical records must be there within 30 days of enrollmentand students without proper immunization cannot be admitted.

But, Flores says, a nurse is not at every school to be a guard at the gate.

Health officials like Laurie Henefey of the state’s immunization program know they have their work cut out for them.

“It’s a constant battle to get [children] vaccinated,” she says. “There’s never going to be a time where we can say, ‘Oh, we’re done.’”