Teach-ins at university campuses, community book drives, read-alouds of banned books on social media, and rallies in front of the College Board headquarters in both New York and Washington, D.C.

These were among the activities taking place across the country on Wednesday as part of the Freedom to Learn national day of action spearheaded by the African American Policy Forum, which has been critical of state laws restricting how teachers can discuss race in the classroom. The forum is led by Kimberlé Crenshaw, a law professor and civil rights scholar at Columbia University Law School.

A coalition comprising Black scholars, civil rights organizations, national teachers’ unions, students, and others came together against legislative efforts to restrict how teachers can discuss race and address racism, and attempts across the country to ban books from classrooms and school libraries. One target of the day of action was the College Board, which scholars involved in organizing the day of action accused of “appeasing right-wing extremists at a time when a record number of books across the country are being targeted for censorship,” according to a press release from the African American Policy Forum.

The nonprofit organization that administers the SAT college entrance exam and Advanced Placement courses edited out topics such as intersectionality and Black queer studies from its new AP course on African American Studies, which it’s piloting this school year in about 60 schools across the country. These were topics that Florida Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis and state education officials said would run afoul of the state’s law limiting how topics involving race can be taught in K-12 schools.

The College Board has since said scholars and experts from the course’s development committee will make changes to the course framework, though the organization has not elaborated beyond its statement on what changes can be expected and why after requests from Education Week.

“In embarking on this effort, access was our driving principle—both access to a discipline that has not been widely available to high school students, and access for as many of those students as possible,” the College Board said in a late April statement announcing the future changes. “Regrettably, along the way those dual access goals have come into conflict.”

At the time of the national day of action, an Education Week analysis found that lawmakers in 44 states have introduced bills or taken other steps to restrict teaching critical race theory or limit how teachers can discuss racism and sexism, with such restrictions taking effect in 18 states.

Additionally, book bans in K-12 schools have only grown in scope and scale since the fall of 2021.

“For over two years, we have been sounding the alarm about the ways in which these anti-woke, anti-[critical race theory], anti-intersectionality efforts were being used to undermine our democracy, and to dismantle public education,” Crenshaw said in a Freedom to Learn TV livestream on YouTube that featured discussions from scholars and others on the history of systemic racism.

“And let’s have no doubt about what the ultimate goal is about these attacks, about these executive orders. Those who are behind it have told us that this is an effort to attack public education to dismantle it, to give parents the incentive to withdraw their support for public education by using some of the oldest pages out of the book: using racism, using fear, using disinformation to say, these institutions are not safe,” she added.

‘A battle for the future’

As part of the Freedom to Learn day’s activities, dozens of people gathered in front of the College Board’s D.C. office for a rally on Wednesday morning, led by Shavon Arline-Bradley, president and CEO of the National Council of Negro Women.

“We have multicultural leaders of different religions, different backgrounds, different parts of the country, that have united and said on this day, we will push the gas on letting the world know that there is a movement countering those fights against anti-racism,” Arline-Bradley said in an interview ahead of the rally.

College students, activists, and lawyers at the rally decried DeSantis’ ban on the AP African American Studies course, the nationwide escalation of bans on books about people of color and LGBTQ+ people, and legislation across the country limiting access to race and racism lessons.

The speakers emphasized the need for protesters to vote in elected leaders who will defend the freedom to read and learn about Black history and contributions to the U.S.

“What’s at stake right now is not just about … Black contemporary issues, to learn about Black history,” said Damon Hewitt, the president and executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “This is a battle about futures, about Black futures. They don’t want you to learn because they’re scared.”

“We can’t let anyone—governors, attorneys general, entities like the College Board, anyone—stop us from building a future that we deserve,” he said.

Learning Black history allows students to expand their worldview by understanding the context and perspectives of their classmates, and to have more role models who may not look like them, said Emily Leugers from the National Black Justice Coalition.

“As we learn from history, we can better understand … our current political climate and better understand the attacks [that] politicians have made on the Black, trans, and LGBTQ+ community are not new, but a strategy that has been employed many times in the past,” she said. “We must support AP African American Studies and the expansion of inclusive education to all states.”

Students from Morgan State University in Baltimore, a historically Black research university, bused down to D.C. to attend the rally.

“I expect the College Board to take us into consideration and really just think about their actions before they do something because the recoil of not having African American Studies and curriculum is going to affect generations to come,” said Tyrane Graham, a 20-year-old Morgan State student. “It’s not about right now. It’s about the generations to come who won’t know our history and won’t know the value of Black people in America.”

For Arline-Bradley, her hope is that the College Board, with its national reach, can invest in promoting anti-racism in public education. She also sees the possibility of politicians directing the College Board’s curricular decisions as a broader warning.

“If we can see this kind of infiltration of fighting anti-racism efforts in education, what’s going to happen in health care, what’s going to happen in economic spaces? And we know that the College Board can be an ally in that space,” she said.

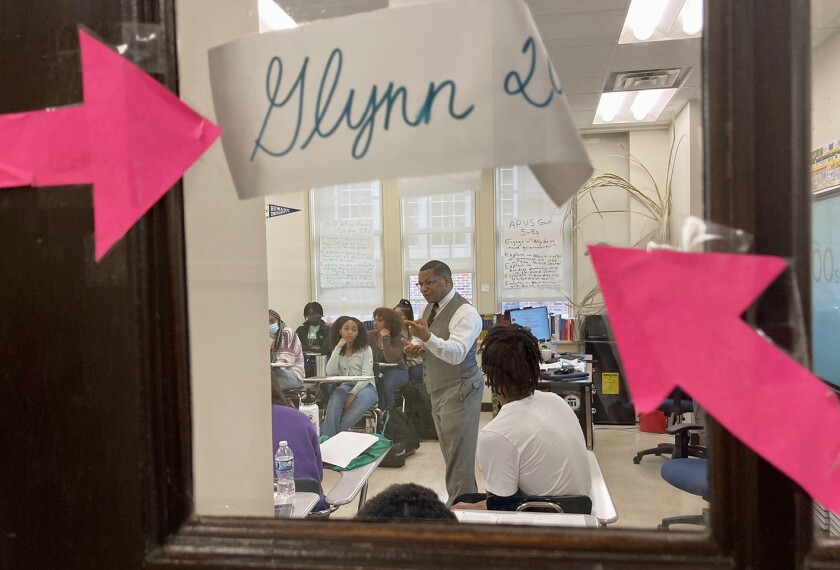

Beyond the day’s rallies in front of College Board headquarters, there were nearly 100 other in-person and virtual events planned across the country.

In Mount Dora, Fla., for instance, a bookstore planned a Bans Off Our Books event.

In Hoboken, N.J., there were plans for film screenings and discussions with librarians and faculty at the Stevens Institute of Technology, College of Arts and Letters.

In Salinas Valley in California, there were plans for either a teach-in or banned book reading at two local high schools.