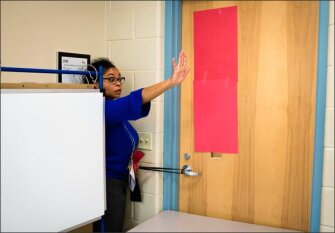

On “safety days,” elementary students in Akron, Ohio, learn a new vocabulary word: barricade.

School-based police officers tell students as young as kindergartners how to stack chairs and desks against the classroom door to make it harder for “bad guys” to get in. “Make the classroom more like a fort,” an officer says in a video of the exercise.

If a teacher asks you to climb out a window, listen to them, the officers instruct. And, in the unlikely event a “bad guy” gets into the classroom, scream and run around to distract him, officers tell students.

For some parents, the idea of such instruction is chilling. Others, though, say it’s a sad, but necessary sign of the times.

Children around the country are increasingly receiving similar training as schools adopt more-elaborate safety drills in response to concerns about school shootings. That leaves schools with a profound challenge: how to prepare young students for the worst, without provoking anxiety or fear.

“That’s the fine balance,” said Dan Rambler, the Akron school district’s director of student services and safety. “We’re not trying to panic people.”

Like Akron, a growing number of school districts around the country have replaced or supplemented traditional lockdown drills—which teach students to quietly hide in their classrooms in the event of a school shooting—with multi-option response drills, which teach them a variety of ways to respond and escape.

Most controversially, the drills also teach young students how to “counter” a shooter by running in zig-zag patterns, throwing objects, and screaming to make it difficult for a gunman to focus and aim.

Akron uses a protocol called ALICE, an acronym for Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, Evacuate. The response was developed by former police officer Greg Crane and his wife, Lisa Crane, a former school principal, after the 1999 shootings at Colorado’s Columbine High School.

It’s grown more popular following the 2012 shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. About 4,000 school districts and 3,500 police departments have ALICE-trained personnel, Crane said.

Outspoken school safety consultant Kenneth Trump, who regularly writes about ALICE training, says it’s not supported by evidence and “preys on the emotions of today’s active shooter frenzy that is spreading across the nation.” Trump and other critics say schools shouldn’t train young children in the ALICE response when school shootings, typically the focus of such drills, are statistically rare.

But fires are also rare, Rambler said, and that doesn’t stop schools from conducting regular fire drills. The Akron district has never had a school shooting or an attempted school shooting either, he said.

Greg Crane, ALICE’s creator, says schools put children in danger if they teach them to be “static targets.”

Parents “don’t have any problem discussing an abduction and giving children quite aggressive tactics in response,” Crane said. “What do we tell kids in stranger danger? Anything but go with the guy. Bite, kick, yell. Anything but go sit in the corner and be quiet.”

Growing Use of Drills

Discussions over security are often sparked by media coverage of shootings. Just last week, a student at a Washington state high school shot and killed a classmate and injured three others before he was subdued by a janitor.

Federal data show a growing use of school-shooter drills, though it doesn’t distinguish between lockdown drills and responses like ALICE. In the 2013-14 school year, 70 percent of public schools drilled students on how to respond to a school shooting, including 71 percent of elementary schools, according to the most recent data available. In 2003-04, 47 percent of schools involved students in shooter drills.

A 2013 federal report, created in response to Sandy Hook, outlined a safety response that called on school staff to “consider trying to disrupt or incapacitate the shooter by using aggressive force and items in their environment, such as fire extinguishers, and chairs.” It didn’t advocate involving students.

That report, released by the U.S. Department of Education on behalf of a group of federal agencies, drew concern from some school safety consultants who said such a “run, hide, fight” approach is unproven by research and may even be dangerous in the event of an actual shooting.

But it also inspired states and districts to update safety plans, leading many to adopt ALICE and similar training. A subsequent report by a task force convened by Ohio’s attorney general, for example, recommended that schools train students and staff that, if a shooter enters a classroom, they try to interfere with his shooting accuracy by throwing books, computers, and phones. They may also need to subdue the intruder, the report said.

In Akron, parents can opt their children out of the training, though few do, Rambler said. Elementary students are told briefly about countering techniques, but the focus of their discussions is on following teachers’ directions in unpredictable situations, he said. In middle school, training is “a little more complete,” sometimes including foam props that students throw at school police officers as practice, Rambler said.

Countering an intruder “is literally the last resort,” Rambler said. “That is, ‘Do whatever you have to to stay alive.’ It’s not, ‘Go find the gunman and throw something at them.’ ”

Planning a Response

Greg Crane said schools decide how detailed they want to be in their hypothetical discussions of violence, but most involve students in some level of training.

The Cranes worked with a children’s author to publish a book called I’m Not Scared ... I’m Prepared! that many schools use to train younger students. But some parents have been concerned about what some districts teach their children in ALICE drills, particularly when it comes to the counter step.

In 2015, an Alabama middle school made headlines when its principal asked students to keep canned goods in their desks to hurl at attackers. At the time, ALICE co-founder Lisa Crane said the use of canned goods is not something ALICE trainers would advocate, but it’s also not something they would discourage.

In some districts, parents have started petitions or turned out to school board meetings in opposition to active-shooter drills, saying they don’t want to expose their young children to such discussions of violence.

“My daughter’s 8-years-old and she reads the newspaper and she gets nervous about stories about murders and other things happening in the neighborhood, so I’m very concerned about what impact it will have on her to be told that there’s a potential that someone might walk through the door and shoot her classroom,” a father said at a public meeting after the Anchorage district announced ALICE training plans last year.

At the National Association of School Resource Officers conference in Washington in July, Officer Ingrid Herriott told school-based police officers and safety directors how she customized ALICE training for elementary, middle, and high school students when she was a school resource officer at Southwest Allen County Schools in Fort Wayne, Ind.

She showed a video she said schools could use to explain ALICE to elementary school children. In it, a school officer explains “stranger danger” to a plush dog named Safety Pup. Police officers are in uniforms, teachers have lanyards and name tags, and strangers are other adults students don’t recognize, the video says. The officer then explains ALICE, advising students to listen to their teacher for directions.

Middle school students quickly learn to barricade doors with desks, Herriott said. She walked middle school students through drills by showing videos produced by the district’s high school students using fake guns to act out school intruder scenarios. In one such video, a student in a library pretends to hit the gunman over the head with a chair.

At that age, the idea of a shooting “isn’t something that’s above and beyond what they are seeing in the media and the video games they are playing,” she said. For high school students, Herriott gave internet surveys after training to learn about concerns, and had principals make follow-up videos to respond to them.

NASRO worked with the National Association of School Psychologists to address concerns about the psychological effects of safety drills. Those recommendations call for plans that are as sensitive to local and regional concerns, like wildfires and earthquakes, as they are to statistically less probable events, like shootings.

Steve Brock, a professor of school psychology at California State University, Sacramento, helped draft that guidance. He said there’s not enough research to support ALICE and similar training in schools.

Minimizing Student Anxiety

The most important thing a teacher can do in a shooting situation is remember to lock the classroom door, he said, and it’s not necessary to “unnecessarily frighten” students by walking them through more elaborate hypothetical scenarios.

“When it comes to these kinds of activities, schools need to proceed cautiously,” he said.

Brock advocates for lockdown drills, which he calls “tried and true” for a variety of crises, ranging from intruders to an intoxicated parent. Such drills have actually been shown to lessen student anxiety, he said. He recommends schools train young students to pretend there’s a strange dog in the hallway that they are trying to stay safe from, rather than talking about “bad guys” or shootings.

But some parents and teachers say responses like ALICE ease their fears that children would be “sitting ducks” in a shooting situation.

After Matt Holland, a 3rd-grade teacher in Alexandria, Va., learned about ALICE in his own staff training this summer, he called his 7-year-old daughter’s school in a neighboring district to ask leaders to transition away from a lockdown approach.

“While, yes, statistically speaking, the chances [of a shooting] are very slim,” Holland said, “I don’t want, heaven forbid, something to happen to my students or my daughter and to say, ‘There was a small chance it would happen, and it happened. And no one ever planned for it.’ ”