This is the third in a series looking at new research on why the effects of successful education interventions often diminish over time. You can read the first installment here and the second here.

Improving education is all about leverage, according to Greg Duncan. If the vast majority of education interventions lose their benefits over time, he believes, it could be because researchers are not looking for the right leverage points.

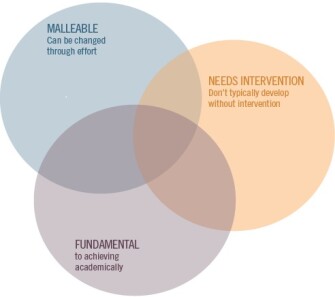

In a forthcoming study, Duncan, a distinguished education professor at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues Drew Bailey of UC-Irvine and Candice Odgers of Duke University identify what they call the “trifecta,” three necessary characteristics not of the intervention itself, but of what the intervention is trying to improve. To cause long-lasting benefits for children, an intervention must target skills, capacities, behaviors or beliefs with three characteristics:

- They must be malleable, or capable of being changed by the educator or school. For example, the researchers noted that “conscientiousness as a personality trait has been very closely associated with students’ school grades and later job performance, but it has proven very stable over a person’s life.”

- They must be fundamental to a long-term goal. For example, prepping for an end-of-year test might improve performance on that test, but generally does not contribute to the student’s long-term literacy or math skills. By contrast, interventions that change a student’s basic understanding of number sets in math or their mindset about intelligence can be applied in many contexts over time and are needed to build other skills.

- They must not be something that students would develop on their own.

That last criterion trips up many promising interventions, according to Duncan’s co-author, Drew Bailey, an assistant education professor.

For example, in a 2013 study in Perspectives in Psychological Science on early-childhood programs, John Protzko, a postdoctoral scholar in cognitive science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, found that interventions that taught parents to engage with their children while reading together raised young children’s IQ by more than 6 points. However, it had no effect on students older than 4, suggesting the programs were accelerating the trajectory of normal language development.

Sharpen Focus on Critical Students and Times

Educators and researchers may also need to narrow their focus, Duncan said. As education as a whole improves over time, the initial differences among students may shift, making it harder to tell which skills will develop naturally and which won’t. In the 1960s and ‘70s, when the federal government was first rolling out education and health initiatives to close achievement gaps between poor and wealthy children, low-income mothers typically had eight to nine years of schooling, in contrast to about 12, and low-income families had on average five children rather than closer to two. Students who did not go to Head Start in its early years generally stayed home, while during the most recent Head Start evaluation, 40 percent of 4-year-olds who did not enter Head Start attended another center-based child-care program.

“The counterfactual conditions that kids faced were much worse than we face today,” he said. The rising tide might lift all students’ boats, but it also makes finding gains harder over time.

Educators may be able to give long-lasting benefits, Duncan said, by tightly targeting students in extremely deprived environments, such as providing interventions to build up normal stress and immune responses in children who had early, chronic “toxic” stress, or supporting emotional self-regulation for teenagers growing up in very violent neighborhoods or households.

Educators can also take advantage of times when a short-term benefit may be all that’s needed to make a difference for students. For example, the H&R Block Project found providing low-income families with help applying for college financial aid during normal tax-filing sessions significantly increased the percentage of poor students enrolling in college after high school. “Knowing how to fill out this long, annoying form is not a fundamental skill—students could learn and forget it the next day—but it gets them over a hump,” Bailey said.

Duncan agreed. “It’s all about being in the right place at the right time with the right kind of intervention to prevent bad things from happening to kids,” Duncan said. “Even if the intervention is boosting some kind of knowledge or capacity, it doesn’t have to have a permanent effect; it just has to get students through some kind of risk period. You don’t want women to never have babies; you just don’t want them to have them as teenagers.”

Duncan and his colleagues are planning new studies now to test the “trifecta” framework. The researchers will look at times when students received a “negative shock,” such as a school closure or a year with a very bad teacher, followed by an intervention known to have positive effects. Duncan said he would like to understand whether interventions might have longer effects by buffering students and helping to “fade out” the damage caused by these negative situations.

If there’s any upside to the tendency of effects to fade out, Duncan said, it’s that the harm caused by bad experiences tends to fade away, too.

Related:

- Positive Mindset May Prime Students’ Brains for Math

- Title I Research: Putting the Program Under the Microscope

- Summer Learning