Corrected: An earlier version of this story gave an incorrect attribution.

Omar Al-Hmoud gets frustrated when Iraqi parents tell him they haven’t enrolled their children in Jordanian schools because they soon expect to be resettled in another country. The deputy country director for Mercy Corps, an international nonprofit organization that provides aid to displaced Iraqis in Jordan, Mr. Al-Hmoud knows that resettlement can be an elusive dream.

He’s concerned that a generation of Iraqi young people are missing out on getting an education while their families wait to move elsewhere.

Mr. Al-Hmoud believes many Iraqi children are not attending school, even though Jordan opened its public schools this academic year for the first time to Iraqis without legal residency. Before the official decree, children were enrolled on a case by case basis, depending on the school, he said.

Imran Riza, the representative in Jordan for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, said in a Feb. 3 interview that the enrollment of 24,000 Iraqis in Jordan’s private and public schools this school year is “extremely low.” U.N. officials had expected about 50,000. As many as 19,000 Iraqi children attended Jordan’s public or private schools before the decree, according to Mr. Riza.

In a recent needs assessment of 3,000 Iraqi families—out of the estimated half million living in Jordan—Mercy Corps found 762 students who weren’t in school. The organization’s staff members will soon conduct a follow-up study to find out why.

But informally, Mr. Al-Hmoud, who is Jordanian, has already identified a few reasons why he believes some Iraqi children aren’t in school. Among them:

• Parents are afraid to step forward because they worry they may encounter problems if they make it known they don’t have legal residency in Jordan.

• Iraqi children are behind academically because they’ve missed so much school.

• Parents may feel their children won’t be comfortable going to school with Jordanian children.

• Families lack transportation.

• Families face serious economic problems.

Nonformal and Informal Programs

Mr. Al-Hmoud points out that the Jordanian Ministry of Education has a regulation barring children who have missed more than three years of school, regardless of their nationality, from enrolling in regular public schools. Many displaced Iraqi children fall into that category. So Mercy Corps, in partnership with Questscope, an international group that works to help the disadvantaged in the Middle East, began this school year to include Iraqi children in “informal” and “nonformal” education programs in Jordan.

Nonformal programs are delivered at public schools and follow a curriculum written by Questscope and approved by the Ministry of Education. Teachers must be certified. Informal programs are meant to prepare students for more formal schooling. Such programs are operated at community-based organizations and don’t need the approval of the ministry. Mr. Al-Hmoud said the informal programs have actually been more attractive to Iraqis than nonformal programs.

At one informal program, in the eastern part of Amman, where many impoverished Iraqi families are living, children take classes for only one or two hours per day. Both Jordanian and Iraqi children attend. The National Society for Rehabilitation of Poor Families, a community-based organization, is involved in running this particular program along with other nonprofit organizations.

English and computer skills are among the lessons taught. For many children, this is the only “school” they attend, though a few are also enrolled in regular schools.

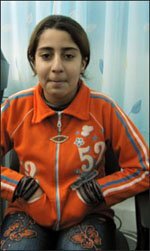

Among the Iraqi students in the informal program is Reyam Saddam, 13. She has been in Jordan for three years and missed two years of school after her family fled the war in Iraq. Now in 5th grade in a regular school, Reyam says she should be in the 7th grade. She said her family left Baghdad after her brother was kidnapped. He was returned to the family.

Fifteen-year-old Aseel Thafir is also in the informal program. Its two hours of classes are his only schooling. He started the 6th grade in Iraq—before moving to Jordan four and a half years ago—but hadn’t been to school since, until enrolling in the informal program this school year. “I’m working to improve myself so I can register in public school,” said Aseel, who dreams of being an engineer like his father. His family left Iraq after both the young man and his brother were kidnapped in two different traumatic incidents. Both were returned to their family.

Dana Anwar, 10, who has been in Jordan for four years, has also not had any formal schooling in that time. Prior to the Iraq war, her family lived in Yemen, where she attended 1st grade. The family returned to Iraq. They then fled their home country to Syria and then came to Jordan. The informal program is Dana’s only schooling. During the day, she runs errands for her mother and helps clean the house, she said.

Mr. Al-Hmoud is determined to get more Iraqi children enrolled at least in nonformal programs, which provide more rigorous classes than informal schooling. The biggest challenge in helping displaced Iraqis in Jordan is “outreach,” he said. The Mercy Corps leader tells Iraqi parents they shouldn’t put their children’s education on hold even though their future in Jordan is uncertain.