In her eight years as North Middle School’s principal, Jeanne Burckhard has been able to point with pride to better attendance, fewer discipline problems, and a program to ensure that low-income students don’t go hungry on weekends, so they’re better able to learn on Monday mornings.

But she continues to be frustrated by an obstacle to achievement that seems particularly pronounced among the Native American students who make up 61 percent of the school’s enrollment: high mobility.

The turnover rate for North Middle students last year was 50 percent overall—meaning that half the school’s 468 students came or went after the start of the school year. Many of them were Native Americans.

And instability carries a cost. Ms. Burckhard cites the steady coming and going of students as one reason the school has always failed to make adequate yearly progress, or AYP, goals under the federal No Child Left Behind Act.

To improve student achievement, North Middle has launched new teaching strategies, after-school tutoring, and family-outreach efforts that—if successful—could hold lessons for other urban and low-income schools with high student turnover.

Missing Out

Experts who study student mobility confirm what educators here in Rapid City, S.D., observe: Children who frequently change schools tend to fall behind academically.

“Particularly in mathematics, students may miss important content being taught if curricula [between schools] aren’t aligned or concepts are taught in different ways,” said David Kerbow, a senior research associate at the Center for Urban School Improvement at the University of Chicago, who has studied student mobility in Chicago’s public schools.

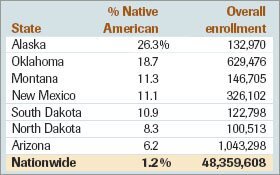

While American Indian or Alaska Native students make up 1.2 percent of all public school enrollment nationally, some states have much higher proportions of such students.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, 2004 data

Addressing Student Mobility

• Develop a personal connection with parents so they have a direct point of contact at school, even if the family moves.

• Create a standard way to quickly assess students who enroll after the start of a school year, particularly in math, reading, and writing.

• Devise a portfolio of student work that can travel with the student from one school to the next.

• Forge links between schools so that staff members can share information about the needs of students who move from school to school.

• Support teachers in helping to integrate students into classes.

SOURCE: David Kerbow, University of Chicago

And the risks can be long-term.

“One of the consistent findings in the dropout literature is that students who have changed schools many times for elementary and middle school are more likely to drop out in high school,” said Mr. Kerbow. Students who don’t move, but attend a school with high student mobility, also are shortchanged because the school tends to slow down the pace of covering the curriculum to accommodate those who are mobile, he said.

Mr. Kerbow’s research also shows a correlation between poverty and student mobility. At North Middle, 89 percent of students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunches.

In Chicago, Mr. Kerbow said, the students who tend to move the most are African-American and those who move the least are white or Asian-American.

“One thing that is different between the low-income and middle-class families in Chicago, in particular, is that the poor families tend to have multiple school moves across their elementary school careers. Middle-class families have moves, but they aren’t multiple moves,” which, he said, are the most devastating for learning.

Another student-mobility expert, Russell W. Rumberger, the director of the Linguistic Minority Research Institute at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said schools need to pay better attention to the social needs as well as the academic needs of mobile students.

“The social side is getting them to feel they fit in,” he said.

Mr. Rumberger said public schools have something to learn from U.S. Department of Defense schools in that respect. “There’s a lot of mobility in the military, but there’s a strong social-support system for families moving from base to base,” he said.

Limited Data

Statistics are limited on the mobility of Native American and Alaska Native students, who make up just 1.2 percent of public school students nationally. But an analysis of data from the National Center for Education Statistics, by an NCES researcher for Education Week, found that 15.7 percent of American Indian or Alaska Native sophomores in 2002 changed schools in their last two years of high school, compared with 7 percent of white sophomores and 8.5 percent of Asian sophomores.

That rings true to some American Indian educators, and it can be a particular challenge in at least five states, where the Native American enrollment is more than 10 percent.

“We seem to have higher mobility of students when the school district is close to a reservation and economic factors come into play, such as the availability of jobs,” said Cathie Carothers, a member of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and the acting director of the office of Indian education in the U.S. Department of Education.

Ms. Carothers said schools often use funds under Title VII of NCLB—which authorized $95 million for Native American students under that section of the law last school year—for tutoring, improving attendance, or increasing graduation rates.

“Students have a hard time meeting requirements for graduation if there is a lot of mobility,” she said.

In Montana, where one in 10 students enrolled in public schools is Native American, student mobility is especially high in urban areas, according to Mandy Smoker Broaddus, the specialist on American Indian achievement for the Montana education department.

“It’s a problem because families in poverty tend not to have stable housing. Kids move around with different family members,” said Ms. Broaddus, who is a member of the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux tribes.

She has experienced some of this mobility in her own family, she noted. When her brother was struggling to support his five children and when she was a single woman attending graduate school, he sent one of his sons to live with her for two of the boy’s high school years.

Catching Up

While North Middle can’t yet point to a reduction in its student mobility, the school has implemented a number of strategies to help students who have gaps in their education.

Mary Bowman, a member of the Oglala Lakota and Hunkpapa Lakota tribes, is an outreach assistant whose salary is paid with Title VII funds. She works one-on-one with 15 to 20 Native American students in their classes—and never assumes that a student who leaves will be gone for good.

“If I start a folder for a kid, I don’t get rid of it,” she said. The school’s principal uses NCLB Title I funds to pay her teachers $20 per hour for after-school tutoring, and to reduce class sizes during the regular school day to an average of 17 students.

In addition, she has trained North Middle teachers in a “workshop” approach to instruction, in which they spend a lot of class time working one-on-one with students.

On a recent fall day, teacher Jackie Swanson credited the workshop approach with helping her to integrate Kiawna Daniels, a new student who arrived that day, into her 8th grade writing class.

Ms. Swanson, a Yankton Sioux who was born and raised in Rapid City, had already greeted the new student warmly in the school office that morning.

The 14-year-old from the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe had started the school year several weeks before at West Middle School, in Rapid City, where she’d enrolled halfway through 6th grade. Before that, she’d attended elementary school on the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota.

The school also is pushing hard to reduce truancy and absenteeism. Truancy officers—and the principal—visit students’ homes if needed, and have been known to coax students out of bed and to school.

Coupling that with a softer approach, Ms. Burckhard has begun a reward program in which students receive $20 in “play money” every day that they get to school by 1st period. They can trade that for school supplies, T-shirts, shampoo, and even more expensive items such as skateboards, all of which come from local donors.

Over eight years, the school’s attendance rate has increased to 92 percent from about 85 percent.

Cultural Approach

Other educators here believe that additional efforts, such as offering a Lakota language and culture class, which began last school year, will motivate Native American students to attend and do well in school.

In the 16 years that he’s worked at North Middle, said Bryant High Horse Jr., a school counselor and member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, the school has come a long way in being more sensitive to Native American culture and “parent connections.” He teaches the Lakota language and culture class at the school.

But he is well aware of the pressures on Native American families that can result in a transient student population.

“In the fall to spring, they are able to find jobs, but no housing, so they will live in motels,” Mr. High Horse said. During the summer and the tourist season, the cost of staying in the motels increases, and they move back to reservations.

Then comes the fall. The families return to Rapid City, he said, “to a different motel—and a different school.”