Amid the understandable, almost unbearable, sorrow in the aftermath of the shootings in Newtown, Conn., last month, we must try to put this tragedy into perspective. Accordingly, educational leaders, parents (including some who gathered to discuss options for safe schools soon after their own children died at Sandy Hook Elementary School), and lawmakers must work together.

As a follow-up to Vice President Joe Biden’s task force on gun-related violence, President Barack Obama issued 23 executive orders and offered preventive proposals, including background checks for all gun purchasers, a ban on semiautomatic assault-style weapons, a limit on the capacity of ammunition magazines to 10 rounds, and new support for mental health and school security.

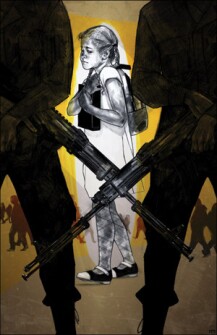

Initially, it is worth noting that insofar as school shootings are rare, political and school leaders must think safety plans through rather than overreact with knee-jerk responses. Among the proposals being bandied about, two, in particular, are best left on the drawing board. As well-intentioned as proponents of these suggestions may be, calls for arming teachers and placing armed guards in schools to defend students, teachers, and others are, simply put, bad ideas.

Before explaining why these proposals are unacceptable, let me begin by pointing out that in spite of my serious reservations about the need of private individuals to own assault-style weapons and/or weapons with high-capacity magazines, I am not taking issue with the Second Amendment. Instead, my focus is on helping to ensure school safety.

To reiterate: School shootings are extremely uncommon. In fact, a recent U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study reported that only 1 percent of childhood homicides, a majority of which involve guns, occur in schools. While the death of even one child is tragic, putting guns into the hands of teachers or placing armed guards in schools can exacerbate tense situations. If policies single out guns, where do we stop? On the same day as the Sandy Hook massacre, an armed man in China slashed 22 students with a knife before being chased off school property by broom-wielding adults. Should officials ban knives? Arm teachers with knives? As awful as school shootings are, weapons are but a symptom of deeper problems associated with violence in our society.

To arm educators who are unlikely to be familiar with weapons and gun safety—whether with openly carried or concealed weapons—is unwise, since this goes against most things for which teachers stand. A flurry of related questions arise, all of which can make bad situations worse. Should teachers be armed? Should only selected teachers be armed? How many teachers are ready, willing, and/or qualified to be armed? What if overzealous teachers mistake visitors for intruders and shoot? Or, in a nightmare scenario, what if armed teachers become mentally unstable and fire on students? What if police officers arrive at schools and confront two individuals with weapons aimed at each other, with both claiming to be teachers? Do the officers fire or wait? Moreover, since handguns are increasingly inaccurate as targets move farther away, will supporters of arming teachers suggest the use of larger, more dangerous weapons in schools? All these situations can lead to greater tragedies by resulting in entirely avoidable “friendly fire” casualties in schools.

Proponents of voluntarily arming educators hope to ready teachers via regular target practice and shooting lessons. While some may learn to fire weapons safely and accurately on controlled shooting ranges, there is no guarantee that educators will be able to do so in crises. Even highly trained police officers, most of whom never fire their weapons in the line of duty, do not always shoot accurately when they must do so. Also, where will teachers keep weapons? In their (hopefully locked) desks? On their persons under concealed-carry schemes? How much time will teachers lose searching for and aiming their weapons rather than getting students to safety during crises? If weapons are left in schools, what prevents intruders (or students) from seeking them out or attacking teachers who may have them on their persons as they enter schools?

What message does arming teachers send to children and communities? Apart from perhaps the most obvious response that violence works, do we turn educational caregivers into armed police agents? Can teachers be mandated to carry weapons? Do we want teachers to be viewed as armed defenders?

Turning to proposals for placing armed guards in schools, essentially reducing buildings to secure compounds, this is unwise for four brief reasons that overlap with the concerns about arming teachers. First, since schools are the safest places for children to be during the day, there is no reason to believe that armed guards will improve situations, especially if individuals or groups enter facilities at locations where protectors are not present. Second, who will pay for training and arming guards? Third, are there better uses for the funds spent on armed guards? Fourth, what message is sent if students must be kept in guarded compounds?

Instead of merely criticizing these proposals for their lack of wisdom or foresight, it is important to take proactive steps to ensure that schools receive needed resources to develop and/or enhance existing, workable security programs. Moreover, it must be acknowledged that in many incidents of large-scale school violence, the shooters had psychological and/or mental-health issues known to staff members.

Rather than devote potentially large amounts of limited educational resources to untested programs to arm teachers or to place armed guards in all schools, three cost-effective options are available.

What message does arming teachers send to children and communities? Apart from perhaps the most obvious response that violence works, do we turn educational caregivers into armed police agents?

First, working in conjunction with social services and community mental-health agencies, leaders should strengthen existing counseling and family programs to assist those most in psychological need. These programs can help identify and serve students (and former students) who suffer from mental illnesses, perhaps offering residential treatment or civil commitment until they are ready to return safely to society.

Second, as at Sandy Hook, educational leaders must adopt and regularly practice comprehensive school safety plans. Like fire-safety exercises, drills can be repeated so educators and students know exactly how to behave before, during, and after crises. It seems likely that the death toll at Sandy Hook would have been even greater without such planning and practice by the staff and students.

Third, as part of safety plans, visitors should be required to check in at centralized locations. This apparently was the case at Sandy Hook, and the building was also secured, although unable to withstand a troubled young man who shot his way in. This suggests that windows and other entrances should be retrofitted, covered by heavy-duty plastic glass or screens, to further limit access to buildings. While it is unfortunate that educators must think in this way, the proverbial ounce of prevention is worth more than the pound of cure.

The sad reality is that at Sandy Hook Elementary, or other school locations, educators are no match against armed, disturbed individuals who are intent on perpetrating large-scale harm. Thus, in the absence of evidence that arming teachers or employing armed guards (who might not be in the right place at the right time) could have altered the outcome at Sandy Hook or elsewhere, educational leaders and lawmakers should consider more proactive means to ensure school safety.