I was sitting in the playroom at the Sudbury Valley School, in Framingham, Mass., pretending to read a book but surreptitiously observing a remarkable scene. A 13-year-old boy and two 7-year-old boys were creating, purely for their own amusement, a fantastic story involving heroic characters, monsters, and battles. The 7-year-olds gleefully shouted out ideas about what would happen next, while the 13-year-old, an excellent artist, translated the ideas into a coherent story and sketched the scenes on the blackboard almost as fast as the younger children could describe them. The game continued for at least half an hour, which was the length of time I permitted myself to watch before moving on. I felt privileged to enjoy an artistic creation that, I know, could not have been produced by 7-year-olds alone and almost certainly would not have been produced by 13-year-olds alone. The unbounded enthusiasm and creative imagery of the 7-year-olds I watched, combined with the advanced narrative and artistic abilities of the 13-year-old they played with, provided just the right chemical mix for this creative explosion to occur.

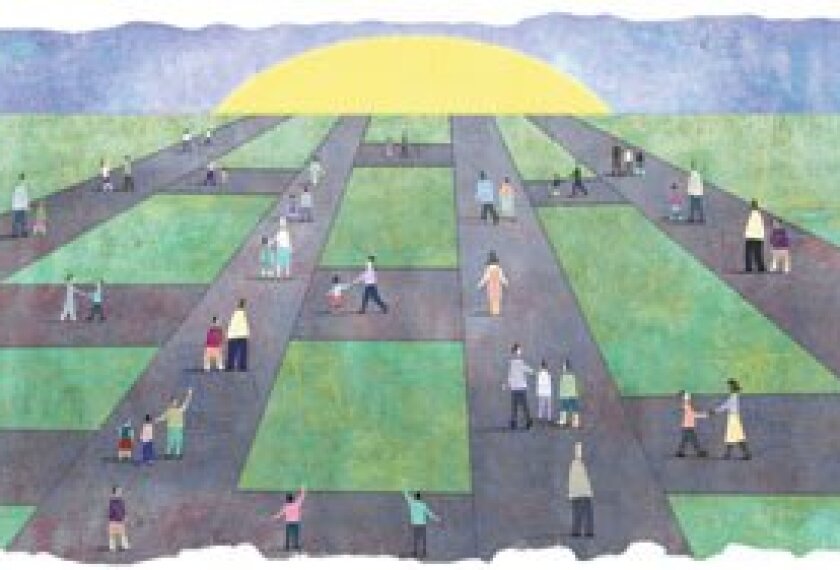

Throughout most of human history, age-mixed play was the norm.

I am a research psychologist, interested in play. My work has convinced me that age-mixed play is qualitatively different from play among children who are all similar in age. It is more nurturing, less competitive, often more creative, and it offers unique opportunities for learning. Throughout most of human history, age-mixed play was the norm. Only with the advent of age-graded schooling and, even more recently, of age-graded, adult-supervised activities outside of school, have children and adolescents been deprived of opportunities to play with others across the whole spectrum of ages. In the course of human evolution, play came to serve its educational functions in age-mixed settings; I contend that it still serves those functions best in such settings.

Most of my observations of age-mixed play have been at the Sudbury Valley School, which is one of the few settings in our culture today where such play predominates. This school, now celebrating its 40th year of operation, has approximately 180 students at any given time, who range in age from 4 to about 18. The students are not assigned to grades, classrooms, or other spaces, and their education is entirely self-directed. They are free to go wherever they wish in the school buildings and campus, and to interact with whom they please. (For more about the school and its graduates, see www.sudval.org.) Daniel Greenberg, one of the school’s founders and the leading exponent of its philosophy, has long contended that the key to the school’s educational success is free age-mixing.

The most obvious advantage of age-mixed play for the younger participants is that it allows them to engage in, and learn from, activities that they could not do alone or just with age-mates. As a simple example, two 4-year-olds cannot play a game of catch together. Neither can throw the ball straight enough or catch well enough to make the game work. But a 4-year-old and a 9-year-old can play and enjoy such a game. The 9-year-old can lob the ball gently into the hands of the 4-year-old and can leap and dive to catch the other’s wild throws.

In the 1930s, the Russian developmental psychologist Lev Vygotsky coined the phrase zone of proximal development to refer to those activities that a child cannot do alone or with others of the same ability, but can do with others who are more skilled. Extending Vygotsky’s idea, the Harvard psychologist Jerome Bruner and his colleagues introduced the term scaffolding as a metaphor for the means by which the more skilled participant enables the novice to engage in a shared activity. In the example just described, playing catch is in the zone of proximal development for the 4-year-old, and the 9-year-old erects scaffolds by throwing gently and by leaping to catch wild throws.

Here’s another example. Children under about age 9 generally cannot play formal card games with age-mates. They lose track of rules; their attention wanders; the game, if it ever begins, quickly disintegrates. But at Sudbury Valley, children younger than this play cards with older children or adolescents. The older players remind the younger ones what they have to do. “Hold your cards up so others can’t see them.” “Pay attention to the cards already played and try to remember them.” The reminders are given just when necessary, to keep the game going and to keep it fun for all. In the process, the younger children become better at paying attention, keeping track of information, and thinking ahead. These are the foundation skills that underlie what we commonly call intelligence.

Similar suggestions and boosts occur in all sorts of age-mixed games—computer games, writing games, outdoor games, informal fantasy games, and rough-and-tumble play. In the name of fun, the older participants naturally, and often unconsciously, erect scaffolds that allow younger ones to stretch and build their physical, social, and intellectual skills. Motivation is no problem in such learning. All of the children are playing because they want to, and they all strive to play well. Many children at Sudbury Valley have learned to read and write, without formal instruction, solely through the scaffolding provided by their playmates.

In the educational literature, Vygotsky’s and Bruner’s concepts are used most often to describe interactions between young children and their parents or teachers. My observations, however, suggest that the concepts apply even better to age-mixed interactions among children and/or adolescents, where nobody is officially teacher or learner, but all are simply having fun. Older children and adolescents are closer in energy level, activity preferences, and understanding to the younger children than are adults, so it is more natural for them than it is for adults to behave within the younger ones’ “zones of proximal development.” Moreover, because older children and adolescents do not see themselves as responsible for the younger children’s long-term education, they typically do not provide more information or boosts than the younger ones want or need. They do not become boring or condescending.

We must find ways to break down the barriers we have erected to keep young people of different ages apart.

The benefits of age-mixed play go in both directions. In interactions with younger ones, older children exercise their nurturing instincts and take pride in being the mature person in a relationship. They also consolidate and expand their own knowledge through teaching. When older children explain rules, strategies, moral principles, or other concepts to younger ones, they have to make their implicit understanding explicit, which may lead them to re-examine what they thought they already knew.

Moreover, just as younger children are attracted to the more sophisticated activities of older ones, older children are attracted to the creative and imaginative activities of younger ones. At Sudbury Valley, we have frequently observed teenagers playing with paints, clay, or blocks, or playing make-believe games—activities that most teenagers elsewhere in our culture would have long since abandoned. In the process, the teenagers become wonderful artists, builders, storytellers, and creative thinkers.

If we want to capitalize on children’s and adolescents’ natural, playful ways of learning, we must find ways to break down the barriers we have erected to keep young people of different ages apart. Age segregation deprives them not only of fun, but also of the opportunity to use fully their most powerful natural tools for learning.