After the initial commotion surrounding the $4 billion federal Race to the Top competition had died down, many observers, including U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, urged the media and the public to take a broader view. The competition has encouraged states across the country—34 of them, plus the District of Columbia—to approve potentially transformative laws or policies meant to improve schools, the secretary noted, by creating support for charter schools and changes to teacher evaluation policy, among other strategies.

But chances are we’ll have a much truer sense of Race to the Top’s impact on education policy a couple years down the road. One person who made this point to me as I was reporting on the competition last week was Paul Manna, a scholar at the College of William and Mary, in Williamsburg, Va. To illustrate the dangers of overstating the immediate impact of federal policy on the states, he pointed to the hullabaloo that occurred back in 2003, when then-President George W. Bush announced in a White House ceremony that all states had completed their mandatory accountability plans, as required by the No Child Left Behind Act. Those plans offered blueprints for ensuring that all students would be proficient in reading and math by 2013-14.

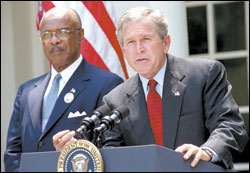

“The era of low expectations and low standards is ending,” Bush said in a Rose Garden speech, “a time of great hopes and proven results is arriving.”

But as became clear in the months and years that followed, many state plans were incomplete and needed modification. As Manna explained, a lot of them had been given only conditional approval by the feds, and many states were struggling to meet critical requirements of the law, such as establishing data systems to monitor student performance. And of course, states ended up setting very different standards for judging students’ proficiency, which some said sabotaged the underlying purpose of the law.

Of course, Race to the Top differs in countless ways from the No Child Left Behind Act, in terms of its overall goals, incentive structures, and the manner in which the feds are asked to oversee state activity. But Manna sees parallels in terms of the uncertainty surrounding states’ ability to carry out their ambitious plans, and also the feds’ ability to hold them to lofty expectations, or in the case of No Child Left Behind, strict mandates.

“We haven’t had the nirvana promised back in 2003,” he told me. “Why do they think it’s any different now?”

Manna explored the challenges states faced in implementing NCLB in depth in 2006 article. Do you think his comparison is apt, in terms of the difficulty of turning states’ visions into reality?