Collaborations popping up across the country between charter and traditional public schools show promise that charter schools could fulfill their original purpose of becoming research-and-development hothouses for public education, champions of charters say.

But both supporters and skeptics of charter schools agree that so far the cooperative efforts are not widespread nor are most of them very deep.

The U.S. Department of Education spent $6.7 million in fiscal 2009 on grants to states for charters to share what they’ve learned with other schools. It is now conducting a feasibility study on ways to support the spread of promising charter school practices, said Scott D. Pearson, the department’s acting director of the charter schools program.

One idea being explored, he said, is to establish a prize for exemplary collaborations.

“We do realize that one of the promises of charter schools was they were going to be a source of innovation and be a benefit not only for the children attending charter schools, but [for] all public schools,” Mr. Pearson said. “The collaboration is not as widespread as we would hope.”

Examples of sharing “are limited in scope or there aren’t that many of them,” said Robin Lake, the associate director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Some skeptics of charter schools contend that some of the “innovations” they are credited with, such as extended time for learning or small school size, originated in traditional public schools.

“There’s not a lot to share. Charter schools are a lot like [regular] public schools,” said Joan Devlin, the senior associate director of the educational issues department at the American Federation of Teachers.

But others, such as the Ohio Alliance for Public Charter Schools, believe charter schools do have some distinctive practices that should be shared with traditional public schools. The alliance hosted a conference in September that featured 26 “promising cooperative practices” between the two kinds of schools. Examples included a Minnesota Spanish-immersion charter school working with a local district to create a Spanish-language-maintenance program, and California charter school and districts teaming up on a teacher-induction program.

“We were trying to move past the whole charter-war debates and move to a more productive place,” said Stephanie Klupinski, the alliance’s vice president of government and public affairs.

One of the more substantive collaborations highlighted by the alliance is a partnership between the 3,400-student Central Falls district and the Learning Community charter K-7 school, both in Central Falls, R.I. The long troubled district drew national attention last year for a protracted dispute between school system officials and the teachers’ union.

The charter school has a contract from the district to provide professional development in teaching reading for K-2 teachers. Ann M. Lynch, the district’s lead elementary administrator, credits the implementation of the reading units from the charter school with helping boost reading scores in Central Falls. The units systematically teach students the same reading skills each year but increase depth with each grade.

Borrowing Best Practices

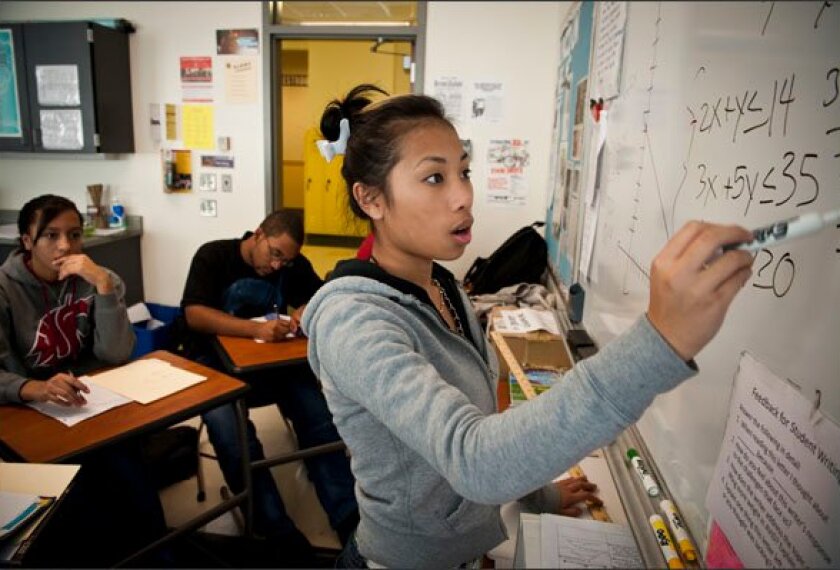

Lincoln High School, in the 29,000-student Tacoma district in Washington state, is also seeing test scores rise after borrowing some practices from charter schools, according to Patrick Erwin, a co-principal with Greg Eisnaugle of the high school.

About 350 of the 1,500 students in the high school attend the Lincoln Center, a school-within-a-school started more than two years ago that implements practices Mr. Erwin says were picked up from the well-known Harlem Children’s Zone, Green Dot, and Knowledge Is Power Program charter schools. The Lincoln Center operates from 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., and is in session for two Saturdays each month. It also uses standards that are more rigorous than the state’s 10th grade standards, for example, and requires teachers to apply for jobs, selecting only those who have shown success in the classroom, according to Mr. Erwin.

He said the school has an agreement with its 15 teachers, in addition to their union contract, to work extra hours, for which they receive extra compensation.

Meanwhile, the 202,000-student Houston Independent School District has begun an initiative to bring some of the practices of high-performing charter and regular schools—with an emphasis on charter school practices—to regular public schools, according to Jeremy Beard, the school improvement officer for that effort. Called Apollo 20, the program began in nine schools this year and will expand to 20 next year.

Five Tenets

The district is working with Harvard University economist Roland Fryer to carry out five tenets he’s identified in researching successful schools: investing in human capital, providing intensive tutoring, extending time for learning, fostering a culture of high expectations, and using data-driven instruction, Mr. Beard said.

But the initiative is being implemented competitively and not collaboratively with charters, said Chris Barbic, the founder and chief executive officer of Yes Prep Public Schools, which runs eight Houston charters. He predicts the district won’t have the same success with the practices his network uses because it is making too many decisions at the district level rather than giving autonomy to school leaders. “We don’t run our schools that way, nor do I think other high-performing charter schools do,” Mr. Barbic said.

Ted Kolderie, the founding partner of Education/Evolving, a nonprofit organization in St. Paul, Minn., and a pioneer in the charter school movement, said early supporters of the idea talked about a “ripple effect,” where charter schools would spur other schools to pick up on their innovations.

But Mr. Kolderie added that he’s learned the conditions in the public schools have to be right for that to happen. “Whether there is a ripple effect depends on the pond and not on the stone,” he said.